As early as 1786 George Washington complained that one of his runaway slaves had been assisted to freedom by a “society of Quakers, formed for such purposes.” Estimates of the number of fugitive slaves who escaped the South along the Underground Railroad network from 1800 to 1860 range from several hundred to two thousand annually.

Despite Levi Coffin’s claim in his autobiography that he was the “President” of what before the age of steam was just the “Underground Road,” the escaped slave assistance network was a classic example of leaderless resistance. Many individuals, both white and black, under no central command, cooperated house to house and neighborhood by neighborhood to pass fugitives along points of safety.

Over his 40-year career, Levi Coffin and his community of Nantucket Quaker emigres in New Garden, Guilford County, NC, smuggled more than 3,000 runaways “contrabands” along the Kanawah Trail, across the Blue Ridge Mountains and through Virginia and Ohio to the Quaker settlement at Richmond, Indiana.

The advent of war in 1861 slowed but did not stop the network’s activities. It did, however, make one important alteration: white federal soldiers, escapees from prisoners of war camps, could also follow the well-worn trail to freedom. Perhaps the last documented escape took place in late 1864.

With the fall of Atlanta and the approach of Sherman’s forces in September, 1864, Confederate forces evacuated the Andersonville prison camp by rail. Eight thousand federal prisoners spent three days in stock cars without food or water before arriving at Florence, South Carolina, a sleepy railroad crossing on the Pee Dee River 110 miles west of Charleston and 107 miles southwest of Wilmington.

Their arrival on September 15th was a surprise to the local guard detail, a single Reserve company of men over 45 and boys under 18. Without food, water, shelter or even a stockade ready, the prisoners themselves were set to work alongside slaves to build their own new prison.

William S. Burson, a 31-year-old native of Salinville, Ohio, saw a chance to escape when prisoners began tearing down rail fences and ranging farther and farther from the camp. Gaining a guard’s permission to “gather firewood,” he triggered a “Race to Liberty” that broke the guard line as 400 prisoners stampeded into the woods and swamps along the river.

Burson, a private of Company A of the 32nd Ohio Infantry, had been captured July 22nd in the fighting around Atlanta. With two other 29-year-old escapees, Benjamin F. Porter, of the 10th Ohio Cavalry and John Henson, of the 31st Illinois Infantry, Burson built a raft and crossed to the far side of the Pee Dee with no idea of where to go. They were found hiding in a cornfield by a Negro overseer named Will, who fed them and “told us to stay in the woods till night, when he would come back… and put us on the road that would carry us straight to North Carolina; and said we need not be afraid of the darkies, as they were all friends to us. And so we found them to be.”

For a week the trio struggled through central South Carolina, chased by bloodhounds, enduring torrential rain without blankets or shelter and suffering diarrhea from eating raw corn. Stumbling blindly through forest and field in moonless, rainy nights, they were frequently aided by negroes who provided them with matches, sweet potatoes, corn bread, chicken and bacon, and risked severe punishment for trading them civilian clothing for their federal uniform jackets.

By Sept 28th the group made across the state border to the turpentine forests of the North Carolina Sandhills. It was still raining, and Burson, nursing a broken rib and already weakened by two months at Andersonville, was in the grip of a fever and bronchitis so severe that he could barely whisper.

Three days later, friendly local negroes guided them to a trustworthy member of the Home Guard, who advised them against trying to join the Union forces at New Bern, NC. Instead he directed them to follow the Plank Road northwest to “a large settlement of Quakers in Randolph County,” where “a secret organization” of Union men, would help them through to Tennessee.

“This man, though dressed in rebel garb, was Union at heart, and I found that the Jeff Davis was government was losing more by such soldiers than it was gaining.”

When they reached the Randolph County settlements in they were taken under the wing of 67-year-old Joseph Newlin, a well-known Quaker who had almost certainly partnered with the Coffins to help fugitives along the Underground Road. For at least a week the three prison escapees would stay in the county, hidden among various local supporters.

Randolph County, a 30-mile square in the heart of North Carolina, had been gripped by internal guerilla warfare during the Revolutionary War, and old grudges were revived to fuel revenge taken 80 years later. A correspondent in August 1864 wrote that “we are getting right in to war at home, neaighbour against neaighbour.”

Rural Randolph was teeming with “outliers” (draft dodgers) and “recusant conscripts” (deserters) hiding in the woods, ‘caves’, and hills. Today’s site of the state Zoo, Purgatory Mountain, took on that name during the war due to its surrounding haze of concealed campfire smoke. Outlawed and hunted by sheriff, home guard and regular army, these roving bands of young men were a constant source of civil strife. Civilian government came close to collapse, unable to enforce the law or protect local citizens. Troops from Raleigh were frequently called in to round up deserters, punish local collaborators, and guard the factories and polling places.

Randolph had also been at the heart of anti-slavery activism. The home of more Friends meetings than any other county in the state, it had been the headquarters of the Manumission Society. Daniel Worth, an anti-slavery missionary, had been tried there in 1859 for distributing “incendiary literature.” Residents of the county had voted against secession in 1861 by a ratio of 57 pro-Union voters to every single Confederate. The editor of the Fayetteville Observer explained the vote by saying that the people of Randolph “are attached to the Union, and they felt that the Union was in danger.”

Despite these sentiments, when North Carolina reacted to Lincoln’s call for troops by seceding, Randolph County’s governing elite enthusiastically responded. In 1861 eight companies of troops were raised by the sons of the wealthy farmers and lawyers. At least some county residents also joined the opposing forces at the same time. Howell Gilliam Trogdon, a native of Franklinsville, joined 8th Missouri Zouave regiment and led the “forlorn hope” attack on the Stockade Redan at Grant’s siege of Vicksburg in 1863. Trogdon became the first North Carolinian to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor- gaining the Union’s highest military award for fighting his southern brethren.

In 1862 the draft forced more county residents to serve the Confederacy, but even then they couldn’t be made to stay. The desertion rate for the 8 Randolph companies was 22.8 percent, as contrasted with 12.2 percent for North Carolina as a whole. In October 1864 alone, Confederate officials reported 150 deserters in the county.

A prime example of a local deserter was a great-grandfather of Randolph County’s best-known modern resident, Richard Petty. William F. Toomes, a 26-year-old blacksmith, initially avoided Confederate service as a vital employee of a Deep River cotton mill. Drafted into the 58th NC Infantry in December 1863, he was sent to the Georgia-Tennessee front. Within two weeks Toomes had deserted his Confederate regiment and joined the U.S. Army, serving with the 10th Tennessee Cavalry through the end of the war.

The war would prove devastating to the county’s political structure, wiping out most of the next generation of the antebellum power brokers. This first became evident in the election of 1864, held just 6 weeks before Burson arrived in the county, when Peace Party candidates had swept the local vote. Referring to the unsuccessful candidate for governor, a correspondent wrote that “every old Bill Holdenite in the county is elected, and old Bill beat Vance in Randolph!”

William Burson, recovering from his illnesses, was housed near Franklinsville with “a strong friend of the Union, and of course a bitter enemy of the so-called Confederacy.” His host grew to trust Burson, and initiated him into the lodge of the “Secret Order” modeled on the Masons, “the mysterious order H.O.A., which organization was doing almost as much injury to the rebel cause as an invading army.” The HOA, or “Red String,” referring to the Biblical cord of Rahab which allowed Joshua to infiltrate the city of Jericho, had been a major issue in the state elections held in August. The “President” of the order told Burson he had been in the southern army in Virginia, but had “turned his steps homeward, and at once opened a station on the Underground Railroad.”

Franklinsville, like the rest of Randolph County, had been split by the war. One of the state’s premier cotton mill villages, and the largest urban community in the county, its first factory had been founded in 1838 by Levi Coffin’s cousin Elisha, who sold stock in the company to Quakers and anti-slavery activists. The town had been named after Jesse Franklin, an obscure governor and congressman venerated by abolitionists for voting to keep slavery out of the Northwest Territory. In 1850 a Wesleyan, or “Abolition Methodist” meeting house had been established there by missionaries from Indiana.

In the 1850s slaveowners took control of the factory in a hostile takeover, and with the advent of war production was almost entirely diverted into weaving and sewing undergarments for the military. The populace remained pro-Union, however. As early as June,1861, pro-government citizens had warned that Franklinsville had “Abolitionist and Lincolnite among us who defy the home guards”.

Franklinville was one of a number of communities, said an irate Confederate in 1863, “that are thoroughly abolitionized… Those people… read the New York Tribune before the war [Horace Greeley’s antislavery newspaper]…. They wanted a Lincoln electoral ticket- & because they could not get it, many of them refused to vote at all. Go into their houses now & you will find the Tribune and other abolition Journals pasted as wallpaper in their rooms.”

The “President” of the HOA around Franklinville was probably Reuben F. Trogdon, a cooper and post-war Republican sheriff of the county. Burson noted that the Trogdon family was “widely known as being very hostile to the cause of Jeff Davis… so closely watched by the rebels that they… did not dare sleep in their houses at nights. I found among them men who had not slept in their houses for two years, and some who had not eaten in their houses for six months. They were compelled to camp out in the woods, in order to hide from the rebel soldiers who would frequently make raids on the Union men, and if caught… they would, in almost every case, murder them outright.”

Burson’s HOA contacts helped him map out a route to join the Union army in Tennessee that took them through all of the pro-Union “Quaker Belt” counties of North Carolina: Guilford, Stokes, Yadkin, Wilkes, Watauga, and Ashe, where HOA contacts could guide them along the way.

In Ashe County they lost their way and Henson and Porter were recaptured and sent back to the Confederate prison at Salisbury. Burson managed to escape on foot, only to be intercepted by more Home Guards while trying to cross the New River. He was taken to the town of Boone, where he escaped with the aid of another HOA member. From Blowing Rock, NC, suffering more trials and tribulations, he made it through Cumberland and Unicoi counties, TN, to the Union lines at Bull’s Gap, in Hawkins County.

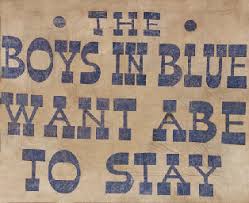

Burson had walked more than 400 miles in 55 days since escaping from Florence. His first act upon reaching Union lines on November 8th was to vote. It was Election Day, and the Underground Railroad had delivered a vote for Abraham Lincoln from the Unionists of Randolph County, NC.