Many Confederate monuments erected at or around the same period were used overtly to advance a racist agenda. “Silent Sam,” on the Chapel Hill campus, for example, was dedicated in 1913 by Civil War veteran Julian Carr of Durham, then the president of North Carolina’s United Confederate Veterans. Carr stated that he and his fellow veterans , Carr applauded rebel soldiers for preserving “the very life of the Anglo-Saxon race in the South,” and ensuring that the “the purest strain of the Anglo Saxon” lived there.

Many Confederate monuments erected at or around the same period were used overtly to advance a racist agenda. “Silent Sam,” on the Chapel Hill campus, for example, was dedicated in 1913 by Civil War veteran Julian Carr of Durham, then the president of North Carolina’s United Confederate Veterans. Carr stated that he and his fellow veterans , Carr applauded rebel soldiers for preserving “the very life of the Anglo-Saxon race in the South,” and ensuring that the “the purest strain of the Anglo Saxon” lived there.

Carr concluded with an overtly racist and threatening anecdote:

One hundred yards from where we stand, less than ninety days perhaps after my return from Appomattox, I horse-whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds, because upon the streets of this quiet village she had publicly insulted and maligned a Southern lady, and then rushed for protection to these University buildings where was stationed a garrison of 100 Federal soldiers. I performed the pleasing duty in the immediate presence of the entire garrison, and for thirty nights afterward slept with a double-barrel shotgun under my head.

My reading of the record does not find any evidence that this was the case when the UDC planned or dedicated the Asheboro monument.

Elvira Evelina Worth Walker Moffitt, Governor Worth’s daughter, was involved with community improvement projects at all stages of her life. During the Civil War, she organized the women of Asheboro to sew tents out of material woven by the mills in Cedar Falls and Franklinville. During the Spanish-American war she helped establish the Soldiers’ Aid Society in Raleigh; during World War I she was a leader in the War Relief Society of Richmond, Va.

Elvira Evelina Worth Walker Moffitt, Governor Worth’s daughter, was involved with community improvement projects at all stages of her life. During the Civil War, she organized the women of Asheboro to sew tents out of material woven by the mills in Cedar Falls and Franklinville. During the Spanish-American war she helped establish the Soldiers’ Aid Society in Raleigh; during World War I she was a leader in the War Relief Society of Richmond, Va.

Besides being honorary president for life of the Johnston-Pettigrew Chapter of the UDC, she was honorary state regent for life of the DAR. She was an early member of the NC Literary and Historical Association and served as editor of the North Carolina Booklet, its history magazine. She was one of the first to suggest that Asheboro and Randolph County needed a public library; she was a founder of the Randolph County Historical Society and of the Women’s Club of Raleigh.

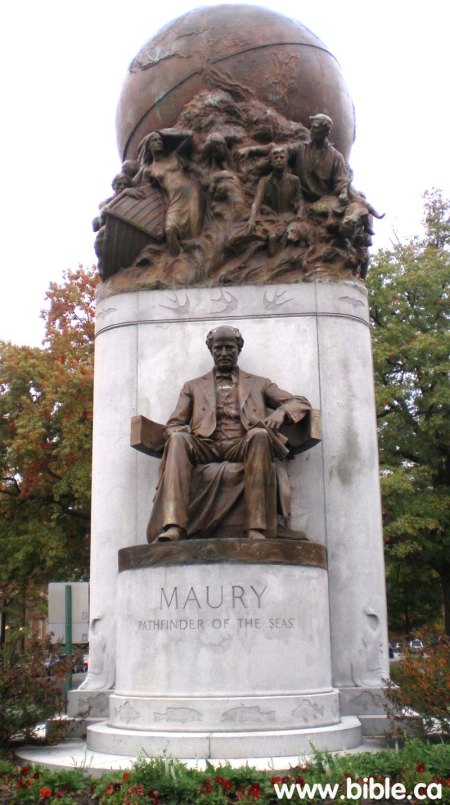

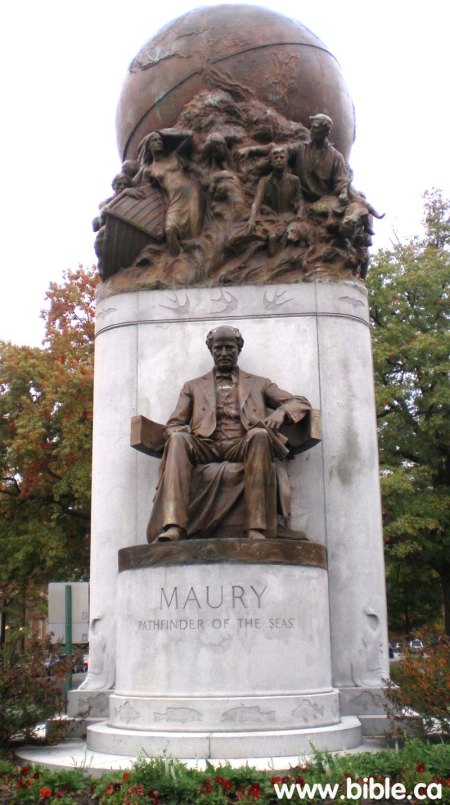

She was instrumental in having a bronze tablet to “Ladies of the Edenton Tea Party-1774” placed in the rotunda of the state capitol; and she was the chief fundraiser in building the Stanhope Pullen Gate, which stands at the entrance to the grounds of NC State University. When she moved to Richmond to live with her son, she joined the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities and personally launched the movement to organize the Matthew Fontaine Maury Association, presiding just a few months before her death at the unveiling of a monument to America’s first and foremost oceanographer. Maury’s statue is perhaps the least Confederate of any on Richmond’s Monument Avenue, excepting that of Arthur Ashe.

She was instrumental in having a bronze tablet to “Ladies of the Edenton Tea Party-1774” placed in the rotunda of the state capitol; and she was the chief fundraiser in building the Stanhope Pullen Gate, which stands at the entrance to the grounds of NC State University. When she moved to Richmond to live with her son, she joined the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities and personally launched the movement to organize the Matthew Fontaine Maury Association, presiding just a few months before her death at the unveiling of a monument to America’s first and foremost oceanographer. Maury’s statue is perhaps the least Confederate of any on Richmond’s Monument Avenue, excepting that of Arthur Ashe.

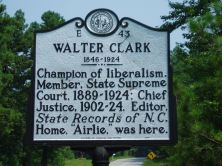

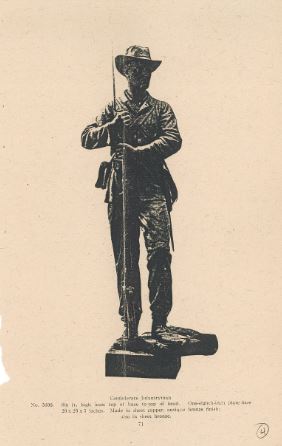

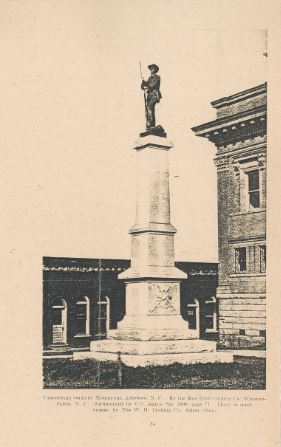

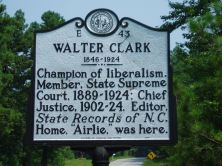

I think Mrs. Moffitt and the UDC members would have agreed with Chief Justice Clark (considered one of the most progressive political figures of his era) that the Asheboro Confederate Monument was first and foremost a Veteran’s Monument. It depicts only a common infantry soldier, not any general or divisive political figure. While Confederate history can and has often been co-opted to advance a racist agenda, and lately has also been hijacked to provide rallying points for domestic terrorism, the history of the Confederacy is unavoidably the history of the American South, just as much as is the history of slavery. Monuments such as ours have been part of the civic landscape of the country for decades, and have now become intertwined with the history of two world wars, civil rights battles, and courtroom drama of all kinds. It may be unintentional that Asheboro’s Confederate monument faces South, while the norm was to site them facing resolutely North. I prefer to see it as a subtle and intentional reference to Randolph County’s reluctant participation in the war, and to the constant desire of its men to come back home.

The NC General Assembly in July 2015, passed the “Historic Artifact Management and Patriotism Act,” (Senate Bill 22), which prevents the removal of monuments such as the Confederate Statue in Asheboro. But protestors in Durham recently ignored the law and pulled down a similar statue at the old Durham Courthouse. If such a law did not “protect” our monument, what would be a valid argument against removing or destroying it?

The NC General Assembly in July 2015, passed the “Historic Artifact Management and Patriotism Act,” (Senate Bill 22), which prevents the removal of monuments such as the Confederate Statue in Asheboro. But protestors in Durham recently ignored the law and pulled down a similar statue at the old Durham Courthouse. If such a law did not “protect” our monument, what would be a valid argument against removing or destroying it?

For an apt comparison out of history, consider the actions of the Allied forces occupying Germany after World War II. Directive 30, issued in May of 1946, directed the “de-nazification” of Germany by ordering the removal of all National Socialist emblems and insignia, and prohibited the “design, erection, installation or other display” of any monument, memorial, poster, statue, edifice or highway name marker “which tends to preserve and keep alive the German military tradition, to revive militarism or to commemorate the Nazi Party, or which is of such a nature as to glorify incidents of war…”

However, Article IV of the Directive states:

However, Article IV of the Directive states:

“The following are not subject to destruction and liquidation:

- Monuments erected solely in memory of deceased members of regular military organizations, with the exception of paramilitary organizations, the SS and the Waffen SS.

- Individual tombstones existing at present or to be erected in the future, provided… the inscriptions… do not recall militarism or commemorate the Nazi Party.”

I would argue that the Asheboro Confederate monument was “erected solely in memory of deceased members of regularly military organizations”, albeit members who served in a losing cause in rebellion against the constituted government of the United States of America. If it was removed at the request of any individual or group which is offended or disagrees politically with the history of the monument, I think a precedent would be created that would make it difficult to refuse an identical request made by any anti-Vietnam War activists.

But don’t people have a point? Isn’t Confederate history racist history?

Yes.

Despite many modern attempts to re-write history, the war that began in April 1861 was fought by Southerners to defend and protect their “peculiar institution.” Attempts to recast and redefine the roots of the war began in Reconstruction and have continued ever since, particularly during the Jim Crow era in the South. The only reason for states to leave the federal Union was to keep slaves in bondage. “State’s Rights” was an excuse put forward to maintain the system of Negro slavery. That was wrong then, and we fought a war to end it. The United States won. The Confederacy lost.

The more pertinent question in regard to this particular monument is whether Confederate history is Randolph County history. My opinion as a Randolph County historian is that our local history was significantly different in many important ways from traditional Confederate history. And our unique local history has never been recognized, commemorated or memorialized in ways that would give it the educational value it deserves.

I’ve been told by those who object to the Confederate statue that their biggest objection is to the inscription, “Our Confederate Heroes.” I think this is a valid point. There were many more heroes in the conflict than just Confederate heroes. Randolph County history of the period is full of examples.

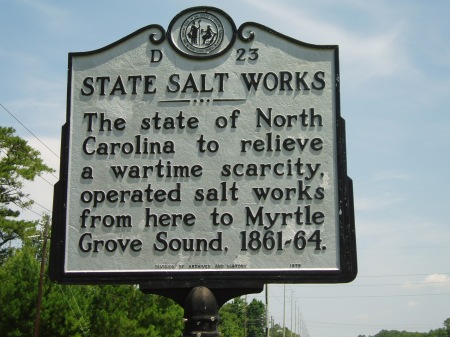

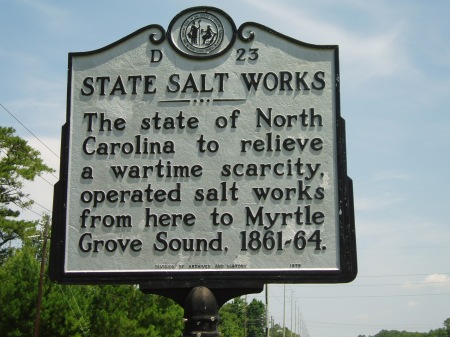

Quaker COs were sent to the Salt Works, run by John Milton Worth.

Quaker COs were sent to the Salt Works, run by John Milton Worth.

Our county had one of the lowest slave population percentages of any North Carolina county east of the mountains. It had one of the highest percentages of “free people of color,” former slaves who had been emancipated before the war years. This was due to the fact that Quakers historically made up the predominant religious group in the county, and the Friends had been in the forefront of manumission and abolition activities in North Carolina since the 18th century. The Quakers from Randolph and Guilford counties were in the forefront of those smuggling slaves out of the South on the Underground Railroad. It is perhaps no surprise that there are no Quaker monuments, as Friends did not even mark their own graves with more than an uninscribed rock until after the Civil War.

When the war did finally come, Randolph County residents were reluctant to embrace it. When the state legislature called for a referendum on secession, Randolph County’s state senator Jonathan Worth actively campaigned against it. The Greensboro Patriot editorialized, “The 28th of February, the day which perhaps will decide the fate of the Union, is close at hand.… Let every man then who loves his country be at his post… There is a battle to be fought. A battle upon the result of which hang the destinies of this Nation. The enemies of our Union have been marshaling their forces. The hand is already uplifted to strike down the flag of our country! Union men, to the rescue! To the rescue! ….”

When the war did finally come, Randolph County residents were reluctant to embrace it. When the state legislature called for a referendum on secession, Randolph County’s state senator Jonathan Worth actively campaigned against it. The Greensboro Patriot editorialized, “The 28th of February, the day which perhaps will decide the fate of the Union, is close at hand.… Let every man then who loves his country be at his post… There is a battle to be fought. A battle upon the result of which hang the destinies of this Nation. The enemies of our Union have been marshaling their forces. The hand is already uplifted to strike down the flag of our country! Union men, to the rescue! To the rescue! ….”

On that election day, the voters of North Carolina narrowly rejected the secession Convention. But in the Piedmont, the traditional Piedmont Quaker counties overwhelming voted for the Union. Chatham County voted against by a margin of 15 to 1; Guilford by a margin of 25 to 1. In Randolph, editor E.J. Hale exulted in the Asheboro Herald of March 3, 1861: “Listen to the thunder of Randolph!” The final vote of 2,579 against to 45 in favor of secession was the largest in the state– 57 pro-Union voters to every one pro-Confederate secessionist. That lop-sided proportion struck newspapers in eastern North Carolina as fishy… the New Bern Progress [quoted in the April 11, 1861 Greensboro Patriot], headed its editorial “Something Wrong.”

On that election day, the voters of North Carolina narrowly rejected the secession Convention. But in the Piedmont, the traditional Piedmont Quaker counties overwhelming voted for the Union. Chatham County voted against by a margin of 15 to 1; Guilford by a margin of 25 to 1. In Randolph, editor E.J. Hale exulted in the Asheboro Herald of March 3, 1861: “Listen to the thunder of Randolph!” The final vote of 2,579 against to 45 in favor of secession was the largest in the state– 57 pro-Union voters to every one pro-Confederate secessionist. That lop-sided proportion struck newspapers in eastern North Carolina as fishy… the New Bern Progress [quoted in the April 11, 1861 Greensboro Patriot], headed its editorial “Something Wrong.”

But whatever it was continued to be wrong throughout the war. Several times each year during the war, government troops were sent from Raleigh to restore civil order and arrest deserters and “outliers,” or draft dodgers. The county was under martial law for much of the war. In the election of 1864, the anti-Confederate Peace Party or “Red String” candidates won every elected office in the county, from Confederate Congress to Governor to Sheriff. Again, the state newspapers cried foul. But that was the true voice of Randolph County, despite sending more than a thousand of its boys off to war.

Historian Bill Auman points out that Randolph County in 1861 had the third-lowest volunteer rate in the state. The enlistment rate for North Carolina as a whole was 23.8%; in Randolph it was 14.2%. As the war went on, conscription acts were passed by the CSA to force men into service; 40% of the state’s draftees in 1863 came from the recalcitrant Quaker Belt counties, with Randolph contributing 2.7% of its population to the draft that year. North Carolina as a whole contributed about 103,400 enlisted men to the Confederate Army, about one-sixth of the total, and more than any other state. But this does not mean those troops were all loyal Confederates; about 22.9% (23,694 men) of those troops deserted, a rate more than twice that of any other state.

Historian Bill Auman points out that Randolph County in 1861 had the third-lowest volunteer rate in the state. The enlistment rate for North Carolina as a whole was 23.8%; in Randolph it was 14.2%. As the war went on, conscription acts were passed by the CSA to force men into service; 40% of the state’s draftees in 1863 came from the recalcitrant Quaker Belt counties, with Randolph contributing 2.7% of its population to the draft that year. North Carolina as a whole contributed about 103,400 enlisted men to the Confederate Army, about one-sixth of the total, and more than any other state. But this does not mean those troops were all loyal Confederates; about 22.9% (23,694 men) of those troops deserted, a rate more than twice that of any other state.

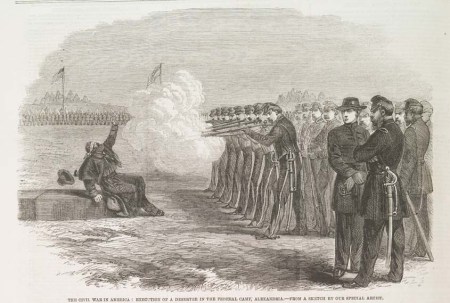

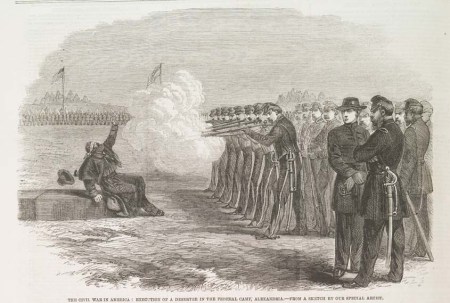

The Confederacy did not publish statistics on desertion, but at least 320 of Randolph’s nearly 2,000 men deserted from their regiments, with 32 deserting twice, five deserting three times and one deserting five times! Forty-four of these deserters were arrested, 42 were court-martialed, and at least 14 were actually executed. So many deserters and outliers hid in underground dugouts, with their camp fire smoke seeping up out of the dirt, that their rugged mountain hideout took on the name Purgatory Mountain- wreathed in the fires of Hell. Even when they returned to Confederate duty, there was no guarantee that these men would stay. 196 captured Randolph county Confederates took the Oath of Allegiance to the Union before the end of the war, with 67 joining the Union Army.

The Confederacy did not publish statistics on desertion, but at least 320 of Randolph’s nearly 2,000 men deserted from their regiments, with 32 deserting twice, five deserting three times and one deserting five times! Forty-four of these deserters were arrested, 42 were court-martialed, and at least 14 were actually executed. So many deserters and outliers hid in underground dugouts, with their camp fire smoke seeping up out of the dirt, that their rugged mountain hideout took on the name Purgatory Mountain- wreathed in the fires of Hell. Even when they returned to Confederate duty, there was no guarantee that these men would stay. 196 captured Randolph county Confederates took the Oath of Allegiance to the Union before the end of the war, with 67 joining the Union Army.

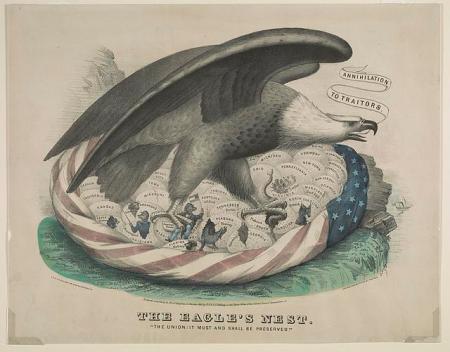

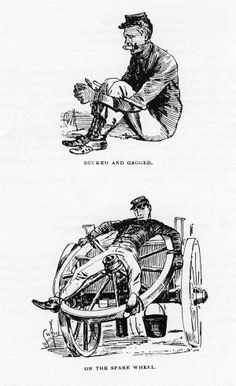

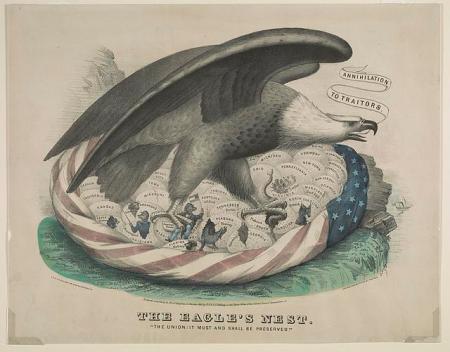

Southern “Volunteers”. Currier and Ives illustration, Library of Congress.

A case in point is the service history of Frank Toomes, great-grandfather of Richard and Maurice Petty. William Franklin Toomes (Jr.) was born October 25, 1838 in the Sumner community of Guilford County, less than a mile north of the Randolph County line. Frank followed his father into the blacksmithing trade, and when the Civil War broke out, both of them were working as blacksmiths, probably at one of the factories in Franklinsville. Male employees of the Deep River cotton mills and ironworks qualified as exempt “indispensable” employees until late in the war, but at some point the regional Enrolling Officer decided the cotton mill could do without one of its blacksmiths. When the Enrolling Officer came for him, Frank Toomes hid, submerged in the mill race, breathing through a straw. But on December 2, 1863 Frank Toomes was captured and forcibly drafted into Company E of the 58th North Carolina Infantry. Within days Toomes was sent to the Tennessee western front, and within days, he deserted. On or around February 1, 1864, 23-year-old Frank Toomes entered the Union lines, surrendered and was taken prisoner to Nashville. On February 12th, he took the Oath of Allegiance to the United States and was assigned to Company H of the 10th Tenn. Cavalry regiment. There Toomes apparently became a good soldier, as he was promoted to 1st Duty Sergeant of Company H on July 16, 1864, and then to Quartermaster Sergeant on June 30, 1865.

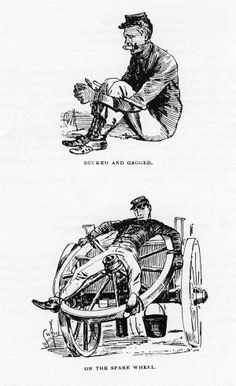

There are also numerous stories about Quaker Conscientious Objectors, who even though drafted, refused to bear arms despite humiliation and torture in the army ranks. Thomas and Jacob Hinshaw, Ezra, Nicholas and Simeon Barker, Simon Piggott and Nathaniel Cox, all Friends from Holly Spring Meeting, were forcibly enlisted in the 52nd NC Infantry when they refused to pay $500 each as an exemption fee. They refused to hire substitutes and they refused to fight, even after being repeatedly “bucked down”- tortured by having their arms and legs bound so they could not move for hours. In camp they were harshly disciplined for refusing to carry guns or participate in military training. An officer wrote that “these men are of no manner of use to the army.” But they were kept in the ranks as virtual prisoners, hands tied and made to march at bayonet point. Finally left on the battlefield at Gettysburg, where they were nursing the wounded, the Quakers were captured by Federal cavalry and imprisoned at Fort Delaware as prisoners of war. A concerted effort by Quakers of Wilmington, Delaware resulted in their pardon and release by Secretary Stanton and President Abraham Lincoln himself.

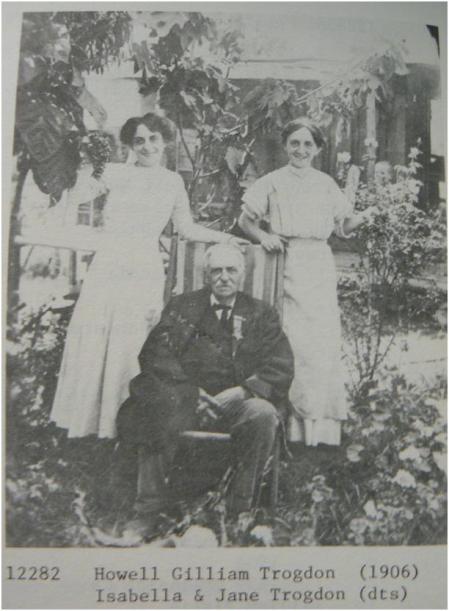

Perhaps the most glaring omission in the Randolph County narrative of its Civil War history is the story of Howell Gilliam Trogdon (1840-1910), a native of the area south of Deep River between Cedar Falls and Franklinville. The Trogdon family is a classic example of one with divided loyalties; half a dozen served in Confederate uniforms and died on the battlefield or served all the way to Appomattox. Many of those who stayed at home became ring-leaders of the secret anti-confederate Peace movement, the Red String. Reuben F. Trogdon, who in 1866 won the vote for Sheriff and served as Randolph County’s first Republican elected official, was said to have been the leader of the Red String during the war. His cousin Howell Gilliam Trogdon, on the other hand, moved to Missouri and became a Zouave in the Union Army. In the seige of Vicksburg, under orders from Ulysses S. Grant, Trogdon led the nearly-suicidal charge against “Stockade Redan,” a Confederate fort. Of the 250 men involved in the charge, only Trogdon and two others made it to the top of the parapet. For his actions in 1863, he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor- the first North Carolinian and the only Randolph County soldier ever to win that honor. Where is his monument?

When I was at Harvard from 1973 to 1977, we took exams in Memorial Hall, a huge Victorian dining hall built in 1869 to honor the 136 Harvard graduates who died while serving in the US Army during the Civil War.

We southerners would morbidly joke that Memorial Hall was the country’s largest monument to Southern marksmanship, a pointed gibe at the fact that nowhere among the marble tablets inscribed with the names of those dead Harvard boys were to be found the names of the 71 southern graduates who also gave their lives.

The Memorial Transept. The names of 136 Harvard Union dead are on those marble plaques.

This is still a bone of contention on campus. http://www.vastpublicindifference.com/2011/05/confederates-in-harvards-memorial-hall.html

Southern monuments aren’t the only one-sided stories of that conflict. But perhaps the lesson is that we need to learn from multiple perspectives, and tell many stories, to get the full picture of history. Erasing one side is just as harmful to real education as is ignoring another.

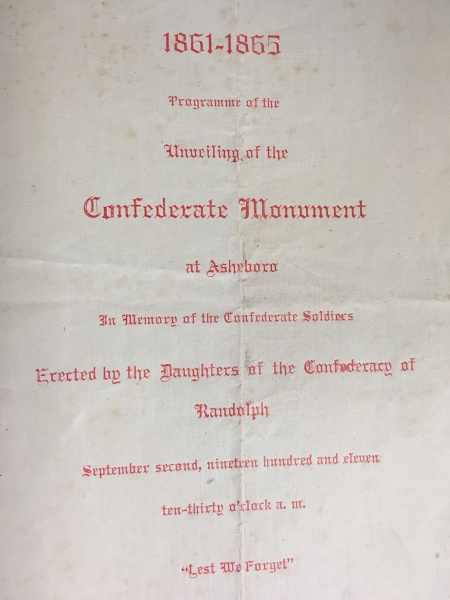

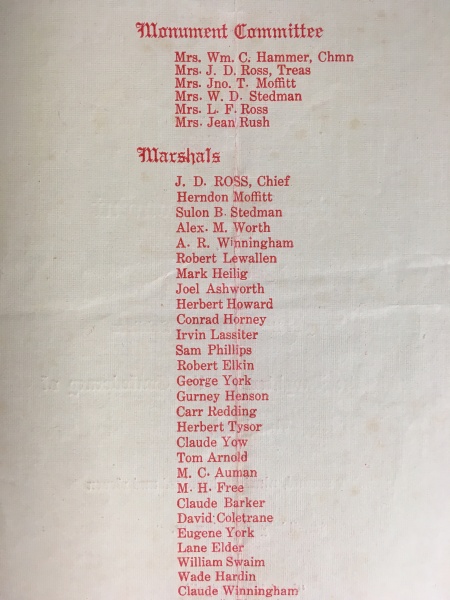

Their final appeal to the general public was published in The Courier of 26 Feb 1909: “We have set our hands to the sacred task of erecting in the town of Asheboro, near our beautiful new courthouse, a monument to commemorate the bravery and valor of the Confederate Soldiers of Randolph County who fell in the War between the States.”

Their final appeal to the general public was published in The Courier of 26 Feb 1909: “We have set our hands to the sacred task of erecting in the town of Asheboro, near our beautiful new courthouse, a monument to commemorate the bravery and valor of the Confederate Soldiers of Randolph County who fell in the War between the States.” “We would that all men in looking upon it might feel that it was a fit expression of the glory of the dead and of the love and reverence of the people for whom they died. It will speak to generations yet unborn of the simple loyalty and sublime constancy of the soldiers of Randolph county who fought without reward and who died for a cause that was to them the embodiment of liberty and sacred right.”

“We would that all men in looking upon it might feel that it was a fit expression of the glory of the dead and of the love and reverence of the people for whom they died. It will speak to generations yet unborn of the simple loyalty and sublime constancy of the soldiers of Randolph county who fought without reward and who died for a cause that was to them the embodiment of liberty and sacred right.”

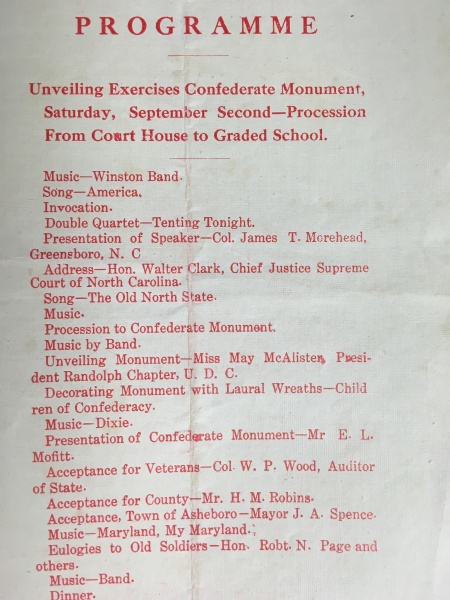

He closed by saying “From what I have already said, it will be seen that from the very beginning of the war to its close, wherever there were hardships to be endured, sufferings to be borne, and hard fighting to be done, there the county of Randolph was represented, and represented with honor, in the persons of her gallant sons.” Absent from Clark’s speech was any “waving of the bloody shirt,” or any reference to “the Anglo-Saxon race” (features of many other such dedicatory addresses). Clark’s only overt political remarks concerned the perceived unfairness that southern states were taxed to provide pensions to Union veterans, but not to Confederate veterans- a position that no doubt resonated with the hundred or more Confederate veterans in his audience.

He closed by saying “From what I have already said, it will be seen that from the very beginning of the war to its close, wherever there were hardships to be endured, sufferings to be borne, and hard fighting to be done, there the county of Randolph was represented, and represented with honor, in the persons of her gallant sons.” Absent from Clark’s speech was any “waving of the bloody shirt,” or any reference to “the Anglo-Saxon race” (features of many other such dedicatory addresses). Clark’s only overt political remarks concerned the perceived unfairness that southern states were taxed to provide pensions to Union veterans, but not to Confederate veterans- a position that no doubt resonated with the hundred or more Confederate veterans in his audience.

The NC General Assembly in July 2015, passed the “Historic Artifact Management and Patriotism Act,” (Senate Bill 22), which prevents the removal of monuments such as the Confederate Statue in Asheboro. But protestors in Durham recently ignored the law and pulled down a similar statue at the old Durham Courthouse. If such a law did not “protect” our monument, what would be a valid argument against removing or destroying it?

The NC General Assembly in July 2015, passed the “Historic Artifact Management and Patriotism Act,” (Senate Bill 22), which prevents the removal of monuments such as the Confederate Statue in Asheboro. But protestors in Durham recently ignored the law and pulled down a similar statue at the old Durham Courthouse. If such a law did not “protect” our monument, what would be a valid argument against removing or destroying it?

However, Article IV of the Directive states:

However, Article IV of the Directive states:

Quaker COs were sent to the Salt Works, run by John Milton Worth.

Quaker COs were sent to the Salt Works, run by John Milton Worth. When the war did finally come, Randolph County residents were reluctant to embrace it. When the state legislature called for a referendum on secession, Randolph County’s state senator Jonathan Worth actively campaigned against it. The Greensboro Patriot editorialized, “The 28th of February, the day which perhaps will decide the fate of the Union, is close at hand.… Let every man then who loves his country be at his post… There is a battle to be fought. A battle upon the result of which hang the destinies of this Nation. The enemies of our Union have been marshaling their forces. The hand is already uplifted to strike down the flag of our country! Union men, to the rescue! To the rescue! ….”

When the war did finally come, Randolph County residents were reluctant to embrace it. When the state legislature called for a referendum on secession, Randolph County’s state senator Jonathan Worth actively campaigned against it. The Greensboro Patriot editorialized, “The 28th of February, the day which perhaps will decide the fate of the Union, is close at hand.… Let every man then who loves his country be at his post… There is a battle to be fought. A battle upon the result of which hang the destinies of this Nation. The enemies of our Union have been marshaling their forces. The hand is already uplifted to strike down the flag of our country! Union men, to the rescue! To the rescue! ….”  On that election day, the voters of North Carolina narrowly rejected the secession Convention. But in the Piedmont, the traditional Piedmont Quaker counties overwhelming voted for the Union. Chatham County voted against by a margin of 15 to 1; Guilford by a margin of 25 to 1. In Randolph, editor E.J. Hale exulted in the Asheboro Herald of March 3, 1861: “Listen to the thunder of Randolph!” The final vote of 2,579 against to 45 in favor of secession was the largest in the state– 57 pro-Union voters to every one pro-Confederate secessionist. That lop-sided proportion struck newspapers in eastern North Carolina as fishy… the New Bern Progress [quoted in the April 11, 1861 Greensboro Patriot], headed its editorial “Something Wrong.”

On that election day, the voters of North Carolina narrowly rejected the secession Convention. But in the Piedmont, the traditional Piedmont Quaker counties overwhelming voted for the Union. Chatham County voted against by a margin of 15 to 1; Guilford by a margin of 25 to 1. In Randolph, editor E.J. Hale exulted in the Asheboro Herald of March 3, 1861: “Listen to the thunder of Randolph!” The final vote of 2,579 against to 45 in favor of secession was the largest in the state– 57 pro-Union voters to every one pro-Confederate secessionist. That lop-sided proportion struck newspapers in eastern North Carolina as fishy… the New Bern Progress [quoted in the April 11, 1861 Greensboro Patriot], headed its editorial “Something Wrong.” Historian Bill Auman points out that Randolph County in 1861 had the third-lowest volunteer rate in the state. The enlistment rate for North Carolina as a whole was 23.8%; in Randolph it was 14.2%. As the war went on, conscription acts were passed by the CSA to force men into service; 40% of the state’s draftees in 1863 came from the recalcitrant Quaker Belt counties, with Randolph contributing 2.7% of its population to the draft that year. North Carolina as a whole contributed about 103,400 enlisted men to the Confederate Army, about one-sixth of the total, and more than any other state. But this does not mean those troops were all loyal Confederates; about 22.9% (23,694 men) of those troops deserted, a rate more than twice that of any other state.

Historian Bill Auman points out that Randolph County in 1861 had the third-lowest volunteer rate in the state. The enlistment rate for North Carolina as a whole was 23.8%; in Randolph it was 14.2%. As the war went on, conscription acts were passed by the CSA to force men into service; 40% of the state’s draftees in 1863 came from the recalcitrant Quaker Belt counties, with Randolph contributing 2.7% of its population to the draft that year. North Carolina as a whole contributed about 103,400 enlisted men to the Confederate Army, about one-sixth of the total, and more than any other state. But this does not mean those troops were all loyal Confederates; about 22.9% (23,694 men) of those troops deserted, a rate more than twice that of any other state.