This is the “Nomination for Cultural Heritage Site” I submitted to the Randolph Count Landmarks Commission that was approved in January 2016. It’s long, but it speaks to an entire segment of local history that has been lost, overlooked, or intentionally buried.

This is the “Nomination for Cultural Heritage Site” I submitted to the Randolph Count Landmarks Commission that was approved in January 2016. It’s long, but it speaks to an entire segment of local history that has been lost, overlooked, or intentionally buried.

For the past several years the abandoned and overgrown cemetery has been cleaned up and made accessible once more by volunteer groups spearheaded by Don Simmons, owner of Magnolia 23 restaurant in Asheboro. Don and I made a concerted effort to local any surviving Odd Fellows, but as Ross Holt discovered, the last one died years ago. The City of Asheboro is now in the process of buying adjoining land and adding the entire tract to the existing Mt. Calvary public cemetery.

The best access to the Odd Fellows Cemetery is via the driveway entrance to Mt. Calvary cemetery adjoining the “Soul Saving Station” at 1124 Cedar Falls Rd., Asheboro. Follow the driveway to the end of the maintained cemetery grounds and the beginning of the wooded Odd Fellow tract.

In February 1953, Mrs. Addie McAlister Keeling, the daughter of Col. A.C. McAlister and grand-daughter of Dr. John Milton Worth, deeded a parcel of land south of Cedar Falls Road to the Town of Asheboro; the lot was evidently already in use as a cemetery “for the Negro population of the Town” (DB 400, PG 637). The cemetery was described as lying east of “Mt. Calvary Drive,” a private road which was also deeded to the Town, which also provided access to the “Odd Fellows Cemetery” (DB400, PG638). For more than 60 years the City has maintained the Mt. Calvary cemetery property deeded to them, but the private “Odd Fellows Cemetery” area to the South, known for generations as “Potter’s Field” or the “Colored Cemetery,” was never officially deeded to the City and gradually became overgrown. It comes as no surprise that the legal history of these tracts are a tangled mess, as in the post-Civil War period neither white nor black citizens took much care to preserve cemetery records. This report attempts to gather together what can be found about this tract of land, and the fraternal order that it is associated with.

In February 1953, Mrs. Addie McAlister Keeling, the daughter of Col. A.C. McAlister and grand-daughter of Dr. John Milton Worth, deeded a parcel of land south of Cedar Falls Road to the Town of Asheboro; the lot was evidently already in use as a cemetery “for the Negro population of the Town” (DB 400, PG 637). The cemetery was described as lying east of “Mt. Calvary Drive,” a private road which was also deeded to the Town, which also provided access to the “Odd Fellows Cemetery” (DB400, PG638). For more than 60 years the City has maintained the Mt. Calvary cemetery property deeded to them, but the private “Odd Fellows Cemetery” area to the South, known for generations as “Potter’s Field” or the “Colored Cemetery,” was never officially deeded to the City and gradually became overgrown. It comes as no surprise that the legal history of these tracts are a tangled mess, as in the post-Civil War period neither white nor black citizens took much care to preserve cemetery records. This report attempts to gather together what can be found about this tract of land, and the fraternal order that it is associated with.

Before 1865, black and white citizens lived together and worshipped together. Negroes, both free and enslaved, lived in and around the homes of the white population where they served, with blacks segregated on the Sabbath into the balconies of both the Presbyterian and Methodist Episcopal buildings. Likewise, there were apparently no separate cemeteries. In the old Asheboro Cemetery on Salisbury street, at or near the site of the original Methodist Episcopal Church, there is a marker headed “To the Memory of our Colored Friends.” Presumably the names inscribed on that granite block are those of Negro citizens buried alongside white citizens and whose original wooden or rock grave markers had vanished.

Before 1865, black and white citizens lived together and worshipped together. Negroes, both free and enslaved, lived in and around the homes of the white population where they served, with blacks segregated on the Sabbath into the balconies of both the Presbyterian and Methodist Episcopal buildings. Likewise, there were apparently no separate cemeteries. In the old Asheboro Cemetery on Salisbury street, at or near the site of the original Methodist Episcopal Church, there is a marker headed “To the Memory of our Colored Friends.” Presumably the names inscribed on that granite block are those of Negro citizens buried alongside white citizens and whose original wooden or rock grave markers had vanished.

Even after churches separated, it isn’t clear that burials became segregated. What appears to be the first church just for African Americans in Asheboro was “Bulla’s Grove,” an African Methodist Episcopal congregation located at or near the site of the present 801 South Fayetteville Street, on the southeast side of Bulla Street intersection. The church was built on an acre of land deeded on January 15, 1869 to David Worth, Jesse Lytle, Donald Steth and J.H. Hoover by local attorney Bolivar B. Bulla and his wife Tibitha. (DB/P- rec. 1-31-1877). It is not known that a graveyard was established around the Bulla’s Grove church; even when the church was rebuilt in 1885 it is unclear if there was an actual Negro residential community around the church or if it was an unsuccessful attempt to create a new African- American neighborhood on what was then the far southern outskirts of the Town, far from both whites and blacks.[i]

In 1921 the Bulla family traded the South Fayetteville location for a new lot on the southeast corner of Burns and Greensboro streets, and Bulla’s Grove took on the name of St. Luke Methodist Church. The history of the church states that the move was “due to the shifting of the Negro population,” but the area on North Main and Greensboro was much closer to the traditional center of Asheboro’s Negro community. Free black citizens had apparently clustered in the North Main area even before the Civil War; the first school for Negro children in Asheboro was established there after 1865.[ii]

The area from Salisbury north to Burns Street and East to North Main, including Greensboro Street, was the subdivision of the Burns family, who lived in a large house on what is now the parking lot of First Methodist Church. Earlier in the 19th century that site had been the home of Benjamin Elliott, whose surrounding farm including all four corners of the Salisbury Street/ Plank Road intersection, and ran North east to what is now Greensboro Street.

Allen’s Temple AME Church, Summit Ave., Asheboro (destroyed)

The new Burns real estate development sold primarily to black families in the same way that that Bulla Street area was earlier developed for the same purpose by B.B. Bulla, and the Old Cedar Falls Road/ Glovinia/ Franks St. neighborhood of “East Asheboro” was developed by the McAlister family. The fourth Negro neighborhood in late 19th century Asheboro was centered around Allen’s Temple A.M.E. Church on Peachtree Street just north of Bossong Hosiery Mill. That church was organized in 1896, but is now gone and only marked by what remains of its graveyard. All but the East Asheboro African- American neighborhoods have been gentrified out of most of their connection to African-American history.

St. Luke Methodist Church, Burns St.

North of Abram’s Creek the African-American community in 19th century Asheboro spread out over the hill crowned by St. Luke’s church, down to the point where North Main forded the stream. The town’s first public school for Negro children was halfway up the hill, established about 1882 and run by William Ernest Mead, a white Quaker missionary from New York. Sidney Robins remembered him

“as master of ceremonies at a Colored Schools Commencement in the Court Room of the old courthouse of an evening. I recall that the white people of the town had been invited, even urged or asked, to be present. Again he was quite in evidence as master of ceremonies at large, with capable Negro teachers managing their classes or prompting their pupils. It was a gala occasion, nothing left out except these gowns for graduates of lower schools that we see nowadays… the Colored schools, or the Negro people of Asheboro, outgrew Uncle Mead or his kind of leadership…. But the thing is natural enough anyhow. I suppose that as our Negro people began to rise, they began to want to do their own flying. They began to want to have teachers and officers of their own race…. He eventually resented a little their graduation in sentiment from his leadership,and that was natural too. They came to seem to him not appreciative enough of that sort of missionary work to which he had given his life. I wonder if all missionaries do not come to share this feeling of his in proportion as they have been successful. If we succeed at all, we make self-starters and democrats out of our pupils.” [iii]

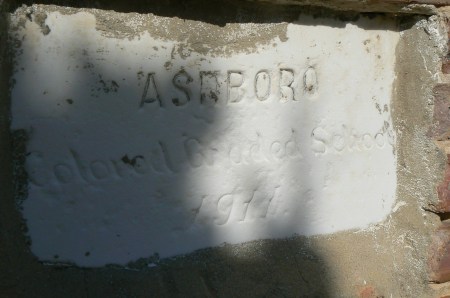

Cornerstone of the 1911 Colored Graded School on North Main Street, now in the foundation of Central High School.

Swaim’s gentle and gentlemanly explanation that the African-American community wanted “to do their own flying” may be the cause that more and more separate black inhe hillside after 1885. But it could also have been the hidden hand of Jim Crow, excluding blacks from membership in white institutions. African-American congregations may well have felt more comfortable with black ministers and black teachers in black churches and black schools. But segregation decreed a separate school system for black children, a system which was not funded on an equal level to the white system.

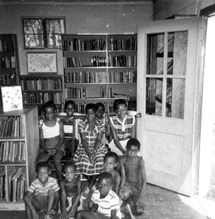

Summer at the East Asheboro branch of the public library, ca. 1950.

Similarly, “fraternal institutions” and “benelovent societies” such as the Masons and Knights of Pythias began as all-white organizations, and when African-Americans sought membership, spun off independent black lodges. Prince Hall, a former slave living in Boston, joined the Masons in 1775, and in 1787 the Ancient, Free and Accepted Masons were established there as the first African-American masonic lodge. With freedom came the ability to freely associate, and more and more African-American institutions came into being. Far from being mere social outlets, African-American fraternal lodges provided burial insurance for members, college scholarships, and assistance during times of illness or death. From 1870 to 1920 these societies were the primary providers of mutual benefits, financial support and care to members and their communities in the days before public assistance and welfare. The most prominent and active African-American fraternal organization in 19th-century North Carolina (and in Randolph) were the now almost-forgotten Odd Fellows.

The name “Odd Fellow” indirectly derives from medieval merchant, trade or craft guild membership practices. “Fellows” were masters of the “art and mystery” or their craft who, in larger communities and cities, banded together in professional associations such as the goldsmiths, glaziers, masons, carpenters and textile workers. In smaller communities where there were too few Fellows of any one trade to form a guild, “Odd Fellows” arose to join together in a “lodge” or union of miscellaneous workers to work together to protect and improve their position in society.

The name “Odd Fellow” indirectly derives from medieval merchant, trade or craft guild membership practices. “Fellows” were masters of the “art and mystery” or their craft who, in larger communities and cities, banded together in professional associations such as the goldsmiths, glaziers, masons, carpenters and textile workers. In smaller communities where there were too few Fellows of any one trade to form a guild, “Odd Fellows” arose to join together in a “lodge” or union of miscellaneous workers to work together to protect and improve their position in society.

The Odd Fellows order is said to have been established by knights meeting in a London pub in 1452, but the earliest surviving records, dated 1748, are of “Loyal Aristarcus Lodge No. 9”, meeting at a London inn. Unofficial lodges are said to have existed in New York in the 18th century, but American Odd Fellowship is agreed to have been founded in Baltimore on April 26, 1819 with the creation of Washington Lodge No.1, chartered by the Manchester Unity of Odd Fellows in England. Their stated purpose was to “Visit the sick, relieve the distressed, bury the dead and educate the orphan.” The Odd Fellows were considered one of the most liberal social organizations, and in 1851 became the only fraternity in the United States to include both men and women. [iv]

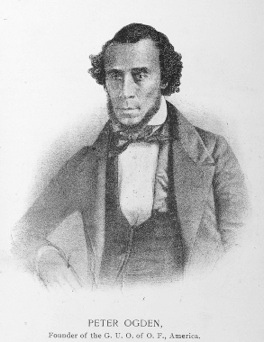

Membership in the American lodges was limited to whites only, despite quite a bit of interest from black citizens. African-Americans in Weldon, N.C. had begun meeting as indepenent Odd Fellows in March 1841, with a second informal lodge formed in Wilmington soon after. In 1842 members of the the Philomathean Institute in New York petitioned the British Odd Fellows to grant them a charter directly. They sent an African American sailor named Peter Ogden to Manchester, where he received a warrant authorizing black Americans to form lodges. The Grand United Order of Odd Fellows was organized in Philadelphia in 1842. Membership has always been open to people of any race, though it has remained a predominantly African American Order. That same year the white American lodges declared their independence from the British lodges, forming the Independent Order of Odd Fellows. The whites only clause was not removed by the IOOF until 1971. The African American Odd Fellows lodges never separated from the English order.[27]

Franklinville Masons, circa 1890.

The period from 1870 to 1920 has been called the “Golden Age of Fraternalism” in America,[v] and Randolph County was no exception. The county’s first white Masonic group met at Hanks’ Lodge in Franklinville starting in 1850 (Hanks Lodge #128 of the Ancient, Free and Accepted Masons), with Balfour Lodge #188 established in Asheboro several years later. By 1880 there were masonic lodges in Ramseur (Marietta #144); Coleridge (Deep River #164); Erect (Mt. Olivet #195); and Liberty? (Oakland #501). The “Pride of Randolph #380,” established in Asheboro around 1880, was apparently the first African-American lodge of Masons.

Hanks Lodge, Franklinville, built 1850.

Another popular national lodge, the Fraternal order of the Knights of Pythias was established as a white organization in 1864. The African-American “Silver Star Lodge #29” of the Knights of Pythias was only established in Asheboro after 1890.[vi] The K.O.P. Met on a lot near St. Luke Church on “the street leading to the Colored Graded School,” a/k/a “School House Street” and now known as Burns Street.[vii] In addition to those fraternities Randolph County in 1907 had lodges of the Loyal Order of Moose, the Woodmen of the World, the Junior Order of United American Mechanics (Trinity, Caraway, Randleman and Franklinville), the “Royal Arcanum” (founded in Boston in 1877 to provide “Widows and Orphans Benefits”); the C.M.A. or “Coming Men of America” (a secret society for boys, founded in 1894 under the motto “Our Turn Next”); and the Improved Order of Red Men (Minnehana Tribe #64 met in Ramseur). Just to confuse things more, there was also an Asheboro lodge of the all-white Odd Fellows, Randolph Lodge #272.[viii]

The Odd Fellows, with large black and white membership, were the largest of all fraternal organizations. From 50 active lodges in 1863, the African-American GUOOF expanded to 2,253 lodges and 36 Grand Lodges in 1897. Although still in existence, membership in the US has declined, due to the mainstream IOOF no longer being segregated, and the decline in fraternal membership in general. The national headquarters of the GUOOF is still in Philadelphia, but since 1981 the national headquarters of the IOOF has been in Winston-Salem.[ix]

A Grand Lodge of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows was organized in North Carolina in 1843, but the first GUOOF lodge of record in the state was the Republican Star Lodge No. 1383 in Elizabeth City established on May 10, 1869 by the Free Virginia Lodge No. 963 from Portsmouth, Virginia. In Raleigh, the Vitru (also seen as Vitro and Virtue) Lodge No. 1616 first met on January 12, 1874.[x]

A Grand Lodge of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows was organized in North Carolina in 1843, but the first GUOOF lodge of record in the state was the Republican Star Lodge No. 1383 in Elizabeth City established on May 10, 1869 by the Free Virginia Lodge No. 963 from Portsmouth, Virginia. In Raleigh, the Vitru (also seen as Vitro and Virtue) Lodge No. 1616 first met on January 12, 1874.[x]

An un-named GUOOF Lodge (“#43”) purchased property in Liberty in 1895[xi], and another (#6737) settled in Randleman in 1908[xii] but the best known and longest-lived Odd Fellowship in Randolph was Diamond Star Lodge No. 3711, organized in Asheboro before 1894. In that year they purchased a lot and building on the west side of North Main Street, just north of the Ross and Rush livery stable.[xiii] Before that time they were said to have been meeting in the upper floor of the McAlister store. In an unusual move, in 1897 the state legislature passed a bill to officially incoporate the Diamond Star Lodge of Odd Fellows in Asheboro. [xiv]

Only a little information can be gained from deed records regarding the philanthrophic activities of the Odd Fellows in Asheboro. In 1921 the Odd Fellows sold a half interest in their property to the “Pride of Randolph #380” Masons[xv]; this may have generated funds that allowed the Odd Fellows to purchase a lot on Greensboro Street “adjoining the School House and Holiness Church,”[xvi] which they sold to the Asheboro Graded School District in 1925.[xvii] This may have been a trade that ultimately resulted in the construction of the new Central School building that replaced the old school on Greensboro Street.

At some point in the early 20th century the lodge apparently acquired a lot south of Cedar Falls Road and north of what is now Martin Luther King Street for use as the first African-American cemetery in Asheboro. When the cemetery was read by the Randolph County Genealogical Society, it was noted as “Oddfellow Cemetery (Also known as McAlister/ Potter/ Oddfellow Cemetery). This cemetery is located behind Mt. Calvary City Cemetery. McAlister Cemetery stars at the fence and goes about 50′. Oddfellow has 1 acre started at the end of McAlister and goes to the next street. Potter is the area next to the brick house on the North end, per Mr. Buddy Matthews. This is a Black cemetery.”[xviii] There were 81 marked graves found in the first two sections, with another 33 unmarked burials discovered from death certificates. “Potter’s Field” is an ancient term for the burial site of paupers and indigent people, the phrase coming from Matthew 27: 3 through 27:8. After Judas Iscariot had hanged himself, the Jewish priests used the 30 pieces of silver paid him to purchase the Akeldama, a pit where potter’s clay had been dug, for use as a stranger’s burial site.

At some point in the early 20th century the lodge apparently acquired a lot south of Cedar Falls Road and north of what is now Martin Luther King Street for use as the first African-American cemetery in Asheboro. When the cemetery was read by the Randolph County Genealogical Society, it was noted as “Oddfellow Cemetery (Also known as McAlister/ Potter/ Oddfellow Cemetery). This cemetery is located behind Mt. Calvary City Cemetery. McAlister Cemetery stars at the fence and goes about 50′. Oddfellow has 1 acre started at the end of McAlister and goes to the next street. Potter is the area next to the brick house on the North end, per Mr. Buddy Matthews. This is a Black cemetery.”[xviii] There were 81 marked graves found in the first two sections, with another 33 unmarked burials discovered from death certificates. “Potter’s Field” is an ancient term for the burial site of paupers and indigent people, the phrase coming from Matthew 27: 3 through 27:8. After Judas Iscariot had hanged himself, the Jewish priests used the 30 pieces of silver paid him to purchase the Akeldama, a pit where potter’s clay had been dug, for use as a stranger’s burial site.

There is no deed on record for the Odd Fellows cemetery, nor the McAlister or Potter’s Field sections; early African-American deeds and wills were often lost before registration, and there is an example of the Odd Fellows themselves obtaining a new deed “to replace a deed that has been lost.”[xix] But as early as 1932, a map of the Burns estate depicts an adjoining “colored Cemetery” between the Cedar Falls Road and the “Road to Franklinville.”[xx] The area shown was generally within the property owned by the John Milton Worth heirs, and known as the “McAlister Estate” after the death of Col. A.C. McAlister. When the Odd Fellows sold their lodge property in 1936, was it to pay for the cemetery?[xxi] In 1953 Addie McAlister Keeling deeded a tract on Cedar Falls Road to the City of Asheboro that was named Mt. Calvary Cemetery, and has since that time been the primary burial ground for African-Americans in Asheboro.[xxii] Its access driveway easement stated that it runs “to the Southwest corner of the Odd Fellows Cemetery.”[xxiii] There is a deed on record to the Odd Fellows from Addie McAlister Keeling, but it is for a lot on Vienna Street that was subsequently sold in 1989 in the last recorded legal transaction by the Trustees of the Odd Fellows.[xxiv]

There is no deed on record for the Odd Fellows cemetery, nor the McAlister or Potter’s Field sections; early African-American deeds and wills were often lost before registration, and there is an example of the Odd Fellows themselves obtaining a new deed “to replace a deed that has been lost.”[xix] But as early as 1932, a map of the Burns estate depicts an adjoining “colored Cemetery” between the Cedar Falls Road and the “Road to Franklinville.”[xx] The area shown was generally within the property owned by the John Milton Worth heirs, and known as the “McAlister Estate” after the death of Col. A.C. McAlister. When the Odd Fellows sold their lodge property in 1936, was it to pay for the cemetery?[xxi] In 1953 Addie McAlister Keeling deeded a tract on Cedar Falls Road to the City of Asheboro that was named Mt. Calvary Cemetery, and has since that time been the primary burial ground for African-Americans in Asheboro.[xxii] Its access driveway easement stated that it runs “to the Southwest corner of the Odd Fellows Cemetery.”[xxiii] There is a deed on record to the Odd Fellows from Addie McAlister Keeling, but it is for a lot on Vienna Street that was subsequently sold in 1989 in the last recorded legal transaction by the Trustees of the Odd Fellows.[xxiv]

Who were the local Odd Fellows? From the deed records cited, the known trustee members of the Diamond Star Lodge from 1894 to 1989 are Henry McSwain, George Staley, Ches Thrift, Zachariah Franks, Wilson B. Baldwin, Charles T. Reed, Allen Garner (1921); George W. Staley, Isaac Craven, Hal Cranford, James T. Morrison, Jr. (1940); John Green, H.B. Cranford, H.L. Leak, John Jiminez (1946); Gladys B. Matthews, Grady Lane, Thomas Ritter (1989). There were likely many more actual members than just the trustees, but unless lodge records surface, their names are not known. Were they a mysterious, secret society like the Masons and Illuminati? How were they regarded in the local community?

Gladis “Buddy” Matthews, whose obituary in 1999 listed him as the last surviving member of the Diamond Star Odd Fellows Lodge.

One of the only published accounts of the public activities of African-American fraternal organizations is a rather biased, condescending and probably racist article published in 1894, largely describing the activities of African-American social organizations in New Orleans and Mobile. I believe it is worth quoting at length for the vivid details it brings to life which are not otherwise available:

The negro now… has become a member of various societies and organizations, generally of a benevolent character, and to these he devotes all the surplus energy of his nature. They have taken the place of politics especially in the thoughts and aspirations of the city negro, and to ride on a gaily caparisoned horse as marshal of his society, wearing a dress suit and a silk hat, with a bright colored sash across his breast, and a truncheon decked with ribbons in his hand, is to reach the summit of the hopes and ambition of many an aspiring descendant of Ham. For one of the main ends and objects of these associations, Odd Fellows, Knights of Tabor, Heart of Hearts, Sons of Zebediah, Daughters of Deborah, Brothers of Lazarus, Sisters of Martha, is to have an annual parade and excursion or picnic. These exhibitions of pomp and pageantry generally take place in the summer, and it is a sight for men and angels to see a procession of colored brothers marching up and down the principal streets of a Southern city on a hot day in July or August, clad in broadcloth and stovepipe hats, with regalia gorgeous enough to call forth the admiration of the white enthusiast in mystic matters… The brass band blares, the horses of the marshals curvet and prance and whisk their plaited tails, and the men in regalia try to keep step to the music with the proud consciousness that the eyes of thousands are upon them. For this great day they have saved and stinted during the whole year, and there is pride and joy in every drop of perspiration that oozes from their foreheads. Crowds of colored people, principally women and children, accompany the procession on the sidewalks and cast admiring glances upon the members, while from hotel, restaurant, barber shop and private residence, members of other societies come out to view the parade critically with emulation in their eyes, and condescension in their approval…. [xxv]

Mention has been made of colored Odd Fellows. Their lodges are not recognized by the white Odd Fellows in this country. It is said that they received their authority, observances, ritual, &c, from an English source. It is certain that in their parades they carry the British flag alongside the stars and stripes. There are quite a number of them in the South. One of the largest processions witnessed by the writer last spring in New Orleans was that of these colored Odd Fellows. It seemed as if they would never get done coming up St. Charles avenue. But these societies are not confined to cities. They exist also in the country, and the negro house servant or laborer, male and female, would sooner go hungry than fail to pay his or her monthly dues. The etiquette in these country societies is very strict on one point, and that is that the members shall never fail to give the titles of “Mr.,” “Mrs.” and “Miss” when they meet or address each other. Occasionally they have candy pullings and other festive gatherings, but the most momentous occasions with them are when the funeral sermon of some member is preached after he or she has been dead some six months or more. For the negro enjoys the luxury of melancholy. His favorite melodies are plaintive, and the songs that colored children sing in their games are in a minor key.[xxvi]

Masks used in Odd Fellows Parades

That this kind of celebration was not limited to the urban South is found in an account in the Asheboro newspaper of the Fourth of July, 1907:

Patriotic Exercises Among the Colored People of Asheboro.

Although the morning of the 4th looked gloomy, at a very early hour numbers of people began to assemble, the first feature of the day being a game of ball between Mitchell and Asheboro. The score was 11 to 18 in favor of Asheboro. At half past seven o’clock the arrival of the Thomasville brass band was announced to the delight of all.

At 2:00 in the afternoon a game of ball was called between Biscoe and Asheboro. As usual the score stood 37 to 1 in favor of Asheboro. The last but not least was at half past six when the band marched to [the] Public Square and played Abernathy and Victory Forever. The music was enjoyed by both white and colored.

The day passed off quietly.

At 12 o’clock the band met the northbound train and escort the crowd to a point where the procession of [GUOOF] Diamond Star Lodge 3711 of Asheboro was formed, after which the band led a march to the First Congregational Church, East Asheboro, where the corner stone was solemnly placed, C.T. Reid acting as master of ceremonies. This was very interesting to all present.

At half past seven o’clock strains of sweet music were heard in the McAlister-Morris building- a high time for the Odd Fellows. This was another marked occasion, everything being in good order. Am glad to say we are advancing toward higher civilization. May the work of God prevail amidst white and colored.

Yours for good, H. DAVID, Pastor, First Congregational Church.[xxvii]

The overgrown cemetery adjoinging Mt. Calvary in East Asheboro is the last surviving remnant of Diamond Star Lodge # 3711, the Asheboro chapter of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows. It is emblematic of the charitable and beneficial work of what may be Asheboro’s first and oldest African-American frateral order. Its history sheds light on a lost world of 19th century African-American culture.

[i] Allen’s Temple AME Church was apparently the second Negro congregation. It was located at the intersection of Chestnut and Peachtree Streets, approximately at the location of 301 Peachtree Street. Allen’s Temple was consolidated with Bulla’s Grove to create St. Luke United Methodist Church.

[ii] The trustees and members of Bulla’s Grove were a Who’s Who of African American Asheboro: William Lytle, George McCain, Benjamin Smitherman, Jordan McCain, John Bell, & Andrew Smitherman; Charlie Reid, Harry Cox, Wesley Brower, Adam Brower, Jeff Hoover, and Thomas Carter. Female members Harriett Hoover, Della McCain, Mattie Pitts, Delphinia Hill, Louisa Bell, Jennie Reid, and Cornelia Brower were responsible for placing the first organ in the church.

[iii] Sidney S. Robins, Sketches of My Asheboro (Randolph Historical Society, 1972), page 27.

[iv] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Independent_Order_of_Odd_Fellows

[v] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_age_of_fraternalism

[vi] Silver Star Lodge #29, Knights of Pythias bought from Jesse Lytle land on East side Fayetteville street at the intersection of the street leading to the Colored Graded School (162/288, 1915) and a year later, another lot on “School House Street” (183/264, 1916) (This is now Burns Street). The trustees of the Knights of Pythias were M.S. Brewer, Albert Henley and Ed Lynn).

[vii] Randolph county Deed Books 162, Page 288 (1915) and 183, Page 264 (1916), purchased from Jesse Lytle. When the property was sold in 1930 (DB227, Pg 421) the KOP Trustees were M.S. Brewer, Albert Henley, and Ed Lynn.

[viii] The Courier (Asheboro), 27 June 1907, “Odd Fellows Elect Officers” C.A. Hayworth was elected Noble Guardian.

[ix] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Independent_Order_of_Odd_Fellows

[x] See the RALEIGH HISTORIC LANDMARK DESIGNATION, 1985, of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows (GUOOF) Building, 115 East Hargett St. http://rhdc.org/sites/default/files/Grand%20United%20Order%20of%20Odd%20Fellows%20Landmark%20App_web.pdf

[xi] Randolph County Deed Book 90, Page 369.

[xii] Randolph County Deed Books 125, Page 207 and 138, Page 247.

[xiii] Randolph County Deed Book 86, Page 106.

[xiv] House bill passed 1 March 1897, cited in Warrenton Gazette, 5 March 1897.

[xv] Randolph Deed Book 208, Page 316 (1921). Trustees of the Masons: Gilmer Davis, J.W. Brown, George Phillips.

[xvi] Randolph County Deed Book 190, Pg. 559 (1921)

[xvii] Randolph County Deed Book 220, Page 212 (1925)

[xviii] Randolph County Genealogical Society journal, date, pages 200-205.

[xix] Randolph County Deed Book 327, Page 125 (1940)

[xx] Plat entitled “Map #3 of the Burns Estate”, Randolph County Deed Book 268, Page 461 (15 March 1932)

[xxi] Their Lot on N. Main Street behind what was the livery stable was sold to B.S. Morris at Randolph County Deed Book 278, Pages 84 & 232, 1936.

[xxii] Randolph County Deed Book 400, Page 637 (25 Feb. 1953)

[xxiii] Randolph County Deed Book 400, Page 638 (Right of Way for Mt. Calvary Drive, 25 Feb. 1953)

[xxiv] A 7752 Square foot lot purchased from Addie McAlister Keeling & h/ Jeffrey “on East side Vienna St.” (Deed Book 354, Page 543, 1946); sold to Matthews in 1989(Deed Book 1249, Page 232). The last named Trustees, were Gladys B. Matthews, Grady Lane, and Thomas Ritter.

[xxv] Ledyard, Erwin. “Social Life of the Southern Negro.” The Southern States: An illustrated Monthly Magazine Devoted to the South. Baltimore: Manufacturer’s Record Publ. Co., August 1894; p.299-300. http://digital.ncdcr.gov/u?/p249901coll37,12204 (accessed August 11, 2015).

[xxvi] Ibid, p. 301.

[xxvii] The Courier (Asheboro, NC), Thursday July 18, 1907, page 8.