“Santa Claus in Camp, 1864” by Thomas Nast in Harper’s Weekly.

Introductory Note:

“Mrs. James Lafayette Winningham…”

On 24 May 1876 Nancy Hannah Steed married James Lafayette Winningham (ca. 1853- 1930), the son of Siebert Francis Marion Winningham and Laura Ann Lyndon. Winningham was born at Union Factory, now Randleman, North Carolina. [Internet geneaological research on the Winningham and Steed families was largely posted by Donald Winningham.]

“…was the daughter of John Stanley Steed and Rachel Director Swaim.”

John Stanley Steed (22 Feb 1829 – 3 May 1899) was the son of Charles Steed (15 May 1782- March 1847), who served Randolph County both as a member of the North Carolina Senate and as a member of the North Carolina House of Representatives. His mother Hannah Raines (born circa 1788- died after 1850) married Charles Steed on 25 Jan 1806. John Stanley Steed married Rachel Director Swaim (15 Nov 1835 – 27 Nov 1880) about the year 1852.

Paragraph 1:

“As I was born in 1857…”

Nancy “Nannie” Hannah Steed was born 14 June 1857.

“My mother always took the children home to her father’s for the holidays”

Rachel Steed’s parents were Joshua Swaim (1804-1868) and Nancy H. Polk (1808 – 14 April 1865), who married in Guilford County on 1 September 1824, but lived in the Cedar Falls area (the area west of Franklinville, south of Grays Chapel, and east of Millboro). The Christmas of 1864 may have stuck in Nannie Steed’s memory because it was the last she would have with her maternal grandmother Nancy Polk Swaim.

Maternal grandfather Joshua Swaim was the son of William Swaim and Elizabeth Sherwood, and nephew of the Clerk of Court Moses Swaim (1788-1870). Joshua and Nancy Swaim were buried in the old Timber Ridge cemetery near Level Cross. Here is a link to photographs of their tombstones: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~davidswaim/TimberRidge.htm

“In their home were our three young aunts and a young uncle, all full of life and fun, and about ten grandchildren.”

Nancy and Joshua Swaim of Cedar Falls had the following children, several of whom had moved West before the time of the Civil War. Numbers 7 through 10 are Nannie’s “young aunts and uncle”:

1. James Polk Swaim (November 21, 1825 – February 04, 1890); m. Sarah McDonald about 1848; died in Franklin County, Ark.

2. Elizabeth Swaim (September 30, 1827- June 28, 1846).

3. Margaret J. Swaim, b. March 22, 1829- February 29, 1848.

4. Mary Swaim (b. ca. 1831); md. Mr. Glass before 1854.

5. William Walter Swaim (February 10, 1833 – died October 17, 1905 in Eldora, Hardin County, Iowa); m. Mary Ann Davis, ca. 1859, in Hamilton Co., Indiana.

6. Rachel Director Swaim, (November 15, 1835 – May 27, 1880); m. John Stanley Steed on October 07, 1852. [Nannie’s Grandma Swaim]

7. Luther Clegg Swaim (b. ca. 1837, d. ca. 1868) [Nannie’s Uncle “Luther Clegg”]

8. Susannah Swaim (b. ca. 1840); m. J.L. Coble, September 04, 1862.

9. Hannah Swaim (b. ca. 1841); m. Henry C. Green, October 06, 1864.

10. Martha Swaim (b. ca. 1847).

{The family information is Included in the Polk family genealogy, posted by Kathy Parmenter at http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/POLK/1999-07/0931116431 }.

“Of us there were my three brothers and myself.”

As of this time in the story, John and Rachel Steed had the following children: Emily, born 1853, who died in infancy; Wiley Franklin, born 1855; Nancy Hannah, born 1857; Henry Luther, born 1860; Joshua Nathaniel, b. 1862.

Paragraph 2:

“The young people had wheat or potato coffee…”

Imports of coffee and other delicacies were reduced almost to the point of nonexistence by the federal blockade of southern ports. According to Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coffee_substitute ), Roasted acorns, almonds, barley, beechnuts, beetroots, carrots, chicory, corn, cottonseed, dandelion root, figs, okra seed, peas, Irish potatoes (but only the peel), rice, rye, soybeans, and sweet potatoes have all been used as coffee substitutes. Roasted and ground wheat as a non-caffeinated substitute for coffee was popular again in the United States during both World War I and II, when coffee was sharply rationed. “Postum” was the brand name of an instant-style coffee substitute made from wheat bran, corn and molasses which was popular in North Carolina in the 20th century, but production was discontinued in October, 2007.

Paragraph 3:

“In our stockings were…ginger cakes…”

Ginger is a tropical root imported from Africa, Jamaica, India or China. It was a much-loved spice during the Civil War era; ginger beer, ginger ale, and all sorts of ginger cakes and breads were popular. Some recipes could be rolled out, cut into shapes and hung on the tree; some were soft like bread and others were hard and crisp. The following recipe from a Civil War reenactor group makes crisp, sugar- coated cookies suitable for putting in a stocking:

3/4 cups shortening

1 cup sugar

1 beaten egg

1/4 cup molasses

2 tsp. soda

1 tsp. cinnamon

1 tsp. ginger

2 cups flour

Combine shortening and sugar into a cream; add the egg and molasses and mix well. Sift together the dry ingredients and add to the shortening mixture. Mix until combined. Roll into walnut sized balls and roll in sugar. Bake at 350 degrees for 7 – 10 minutes.

Paragraph 4:

“…my aunties started the eggnog…”

Various milk punches were known in Europe and brought to America, so the exact orgin of Egg Nog is obscure. “Nog” is an old English word with roots in East Anglia dialects that was used to describe a kind of strong beer which was served in a small wooden mug called a “noggin”. “Egg nog” is first mentioned in the early nineteenth century but an alternative British name was “egg flip,” a punch made with milk and wine, particularly Spanish Sherry.

Internet sites repeatedly cite an unnamed and unsourced English visitor who wrote in 1866, “Christmas is not properly observed unless you brew egg nogg for all comers; everybody calls on everybody else; and each call is celebrated by a solemn egg-nogging…It is made cold and is drunk cold and is to be commended.”

The English author Elizabeth Leslie regularly published cookbooks on both sides of the Atlantic from 1837 to 1857. Her Directions for Cookery, published in 1840, introduced the concept of the “sandwich” to America. This recipe for Egg Nogg comes from the edition of 1851:

“Beat separately the yolks and whites of 6 eggs. Stir the yolks into a quart of rich milk, or thin cream, add half a pound of sugar. Then mix in half a pint of rum or brandy. Flavor with a grated nutmeg. Lastly, stir in gently the beaten whites of three eggs. It should be mixed in a china bowl.”

Perhaps the last word on Confederate egg nog would be the recipe of Mary Custis (Mrs. Robert E.) Lee herself::

-10 eggs, separated

-2 c. sugar

-2 1/2 c. brandy

1/2 c. and 1 tsp. dark rum

-8 c. milk or cream

Blend well the yolks of ten eggs, add 1 lb. of sugar; stir in slowly two tumblers of French brandy, 1/2 tumbler of rum, add 2 qts new milk, & lastly the egg whites beaten light (very fluffy). Allow to “ripen” in a cold but not freezing place; an unheated room or porch was the common location for Mrs. Lee.

From The Robert E. Lee Family Cooking and Housekeeping Book (UNC Press, 2002), by Anne Carter Zimmer.

Paragraph 5:

“…expressed in those days as ‘Christmas Gift’…”

The phrase “Merry Christmas” was popularized around the world following the appearance of the Charles Dickens’ story, A Christmas Carol in 1843. Robertson Cochrane, Wordplay: origins, meanings, and usage of the English language, p.126. (University of Toronto Press, 1996). “Christmas Gift!” is an earlier Southern tradition, used as a greeting. The first person saying it on Christmas morning traditionally received a gift. See “Whistlin’ Dixie: A Dictionary of Southern Expressions” by Robert Hendrickson (Pocket Books, New York, 1993).

Paragraph 6:

“Which is it, the old bad man or the Yankees?”

She is using a euphemism for “the Devil,” a word considered to be so much a curse word at the time that a well-bred young lady was not allowed to use such language. The Devil was on the side of the Yankees, just as God was supposed to be on the side of the Confederacy.

“Little Christmas Waifs Are We”- 19th century Christmas Card

“…the old English custom of the waifs of England.”

It is unclear whether Nannie has here conflated two distinct Christmas rituals from medieval England, or whether the traditions had previously merged in the antebellum South.

The surviving English tradition is of the Christmas “Waits,” musicians and singers who go from door to door “waiting,” or caroling. According to the 11th edition of the Encyclopedia Brittanica, “wait” is the name of a medieval night watchman, who sounded a horn or played tunes to mark the hours. By the 15th century waits had become bands of itinerant musicians who paraded the streets at night at Christmas time, and became combined with another ancient tradition, “wassailing”. It gradually became expected that the musicians would receive gifts and gratuities from the townspeople, and often “those who went wassailing would dress up like street waifs or ragamuffins.” http://www.cafepress.com/+christmas_waifs_sticker,320599343

One other British custom of the Christmas season was specifically aimed at soliciting alms. “Thomasing” anciently occured on 21 December (St Thomas’s Day) when the village poor people visited the homes of their better-off neighbours soliciting food and provisions to help them through the winter. Also called “Gooding,” “Mumping,” and “Doleing,” the earliest reference is from the year 1560, but the custom gradually declined through the 19th century as poor relief was institutionalized, and laws were passed against ‘begging’.

In the South this tradition may have inspired a tradition of inviting local orphans or “waifs” to spend Christmas afternoon with rural families or in urban church socials. [books.google.com/books?isbn=0253219558 ] In 1864 the “ crowning amusement” of Christmas day for the Davis children in Richmond was “the children’s tree,” erected in the basement of St. Paul’s Church, decorated with strung popcorn, and hung with small gifts for orphans. (First Lady Varina Davis’s 1896 article “Christmas in the Confederate White House” makes an interesting contrast to Nannie Steed Winningham’s story of Christmas in rural Randolph County;

http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/on-the-homefront/culture/christmas.html ).

The First Confederate States Flag

Paragraph 7:

“ The Bonnie Blue Flag”

-is a marching song associated with the Confederacy. The song was written to an Irish melody by entertainer Harry McCarthy during a concert in Jackson, Mississippi, in the spring of 1861 and first published that same year in New Orleans. The song’s title refers to the unofficial first flag of the Confederate States, the symbol of secession from the Union bearing the “single star” of the chorus. The “Band of Brothers” mentioned in the first line of the song is a reference to the St. Crispin’s day speech in Shakespeare’s play Henry V.

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Bonnie_Blue_Flag]

Here is the song: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/21566/21566-h/music/bonnie.midi

“The Girl I left behind me”

-is a popular folk tune. The first known printed text appeared in an Irish song collection in 1791; the earliest known version of the melody was printed in Dublin about 1810. It was known in Britain as early as 1650, under the name “Brighton Camp”. It was adopted by the US regular army as a marching tune during the War of 1812 after they heard a British prisoner singing it.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Girl_I_Left_Behind

The song can be heard here: http://www.contemplator.com/england/girl.html

“Hurrah for the Southern Rights, Hurrah! Hurrah!”

-Hurrah! Hurrah!/ For Southern rights, hurrah!” is actually the first two lines of the chorus of “The Bonnie Blue Flag.” ‘Hurrah! Hurrah! For the Southern Rights, hurrah!’ is an alternative reading of the line that is only found in Gone With The Wind, page 236. Both undoubtedly reflect the way singers at the time added ‘the’ to mirror the same article in ‘the’ Bonnie Blue Flag.

“Hurrah! for the Homespun Dress the Southern Ladies Wear”

-”The Homespun Dress,” also known as “The Southern Girl,” or “The Southern Girl’s Song,” is a parody of The Bonnie Blue Flag that oral historians have found in variant versions all over the South. Most authorities attribute the words to Miss Carrie Belle Sinclair of Augusta, Georgia. See Songs of the Civil War, by Irwin Silber, Jerry Silverman; Dover, 1995, p.54. The lyrics can be found at http://www.lizlyle.lofgrens.org/RmOlSngs/RTOS-HomespunDress.htmlv

Oh, yes, I am a Southern girl,

And glory in the name,

And boast it with far greater pride

Than glittering wealth and fame.

We envy not the Northern girl

Her robes of beauty rare,

Though diamonds grace her snowy neck

And pearls bedeck her hair.

CHORUS: Hurrah! Hurrah!

For the sunny South so dear;

Three cheers for the homespun dress

The Southern ladies wear!

Paragraph 8:

“…Mars Luther Clegg had drinked too much eggnog.”

“Mars,” short-hand for “Master,” was used by enslaved people as a general title of respect, in the same way that white people would use “Mister.”

Luther Clegg Swaim was born in Cedar Falls in 1837. On February 1, 1866 he married Dorcas Aretta Odell (1828-1918), daughter of James Odell and wife Anna Trogdon. This was the second marriage for Dorcas Odell, the sister of J.M. Odell and J.A. Odell who worked for George Makepeace in the factory stores at Cedar Falls and Franklinsville. John M. Odell was the first Captain of the Randolph Hornets, Company M. Her brother Laban Odell became Major of the 22nd Regiment, and was killed at Chancellorsville. Her first husband was her second cousin, Solomon Franklin Trogdon, who died in 1860. She had two sons in the first marriage, and a daughter with Luther Clegg Swaim before he died in 1868. Dorcas’s son Williard Franklin Trogdon became the original geneaologist of the Trogdon family, publishing the family history which provided this information in 1926.

Paragraph 9:

“My father and my uncle owned and operated a large tannery, shoe and harness shop.”

The J. S. Steed family is the very first one listed in the Western Division of Randolph County’s 1860 census; his occupation is listed as “Tanning,” and a 17-year-old boarder living with them is listed as “Apprentice Tanner.” Family #2 in that census is David Porter, a buggy manufacturer and grandfather of author William Sidney Porter. I believe the Porters lived on the southeast corner of the intersection of Salisbury Street and the Plank Road (Fayetteville Street)- where First Bank is today.

The 1860 Census of Manufacturing for Randolph County lists “J.W. & J.S. Steed” as engaged in “Tanning… Boot and Shoe Making…[and] Harness Making.” 6 employees in 1859 cured “1400 sides of harness, sole and upper leather” worth $2000; made 40 pair of boots worth $300; 250 pair of shoes worth $500; and 50 setts of harness worth $900.

The Steeds probably lived on Salisbury between Cox and the Plank Road, but the location of his tannery is unclear. The only tannery I am aware of that was ever located in or around Asheboro itself is the one located on the site of the present-day Frazier Park, across Park Street from Loflin Elementary School. The branch that heads in a spring (now piped underground) on that site is called Tan Yard Branch.

“My uncle” refers to the “J.W. Steed” listed on the Census of Manufacturing; this was Joseph Warren Steed (1815-1873), who was elected Sheriff of Randolph County in 1848 after having served as Deputy to Sheriff Isaac White. Sheriff Steed, in politics a Whig, lost the election in 1864 to Zebedee Franklin Rush, the Peace Party (or “Red String”) candidate. The oldest of Charles Steed’s three sons was Nathaniel Steed (3 May 1812 -10 Nov 1880). In 1832 Nathaniel married Sarah (“Sallie”) Redding (9 Oct. 1811 -10 Aug. 1852), daughter of John Redding and Martha Jane Swaim. They are buried at Charlotte Church, on Old Lexington Road west of Asheboro. B.F. Steed, the eldest son of Nathaniel, served as Deputy to his uncle J.W. Steed. The Steeds and Reddings were known for being very tall men, some more than six and a half feet tall.

“Early in 1864 my father… was drafted and sent to eastern Carolina, where he was in the service..”

[Some of you Civil War experts, trace his service record, please.]

Paragraph 10:

“…our faithful family physician, who on account of advancing years bad about given up his practice until the war began…”

Could this have been Dr. John Milton Worth, (28 June 1811 -5 April 1900), who studied at the Medical College in Lexington, Kentucky and practiced in Asheboro up to the time of the war? A substantial part of Dr. Worth’s war years were spent overseeing the Salt Works near Fort Fisher, so this may be some other faithful family physician.

“On the morning of the 10th we were told we had a little brother named for his daddy…”

John Stanley Steed, Jr., born December 1864. The Steeds would have five more children over the next 15 years. Rachel Steed evidently died during childbirth in 1880.

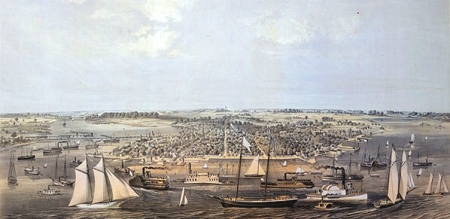

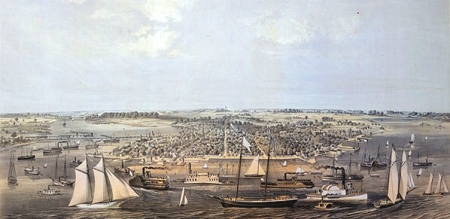

A view of antebellum New Bern from the Neuse River

Paragraph 12:

“There was a man in our town called Captain Pragg, who owned a dry goods store…”

The name “Pragg” is not found in the Randolph County census records for 1860 or 1870, but “Isaiah Prag” does appear in Randolph County marriage bond records for April 19, 1865, when he married “Mrs. Jane Sugg.” This was apparently the second marriage for each of them, as according to family genealogical records “Mrs. Sugg”‘s maiden name was Jane Adaline Andrews (1841-1907). She may have a family connection to Lt. Col. Hezekiah L. Andrews of western Randolph, who was killed at Gettysburg.

Isaiah Prag was born 20 October 1824 in the town of Hadamar in the state of Hesse, Germany. He first appears in America in the 1850 census of Annapolis, Maryland, with wife Rose Adler (1827-1864), and a new baby, Mary. Prag would ultimately have 8 children by his first wife, and 7 by his second. By 1860 Isaiah and family have relocated to New Bern, NC, where he is in business as a “merchant.” From June 1, 1861 to February 10, 1862, the state Quartermaster’s office paid receipts totalling $13,113.20 for purchases from Isaiah Prag. He evidently provided most of the “dry goods” or clothing needed to equip at least two companies of Craven County volunteer troops: Company F and Company K (The Elm City Rifles): 98 suit coats and pants; 74 flannel shirts and 199 striped shirts; 218 caps, 141 pairs of “drawers” and 160 pairs of “pantaloons;” not to mention 556 overcoats- enough for 5 companies!

Isaiah Prag is also listed as an “Ordinance Sergeant” in Company B of Clark’s Special Battalion of the North Carolina Militia, but further details of his military service are not yet known.

Prag’s initial connection to Randolph County is also unclear. It is possible that he was involved with the local factories in the production of underwear under contract to the Quartermaster. His work supplying the army may have forced him to leave New Bern after its capture by federal forces on March 14, 1862. It doesn’t seem likely that Prag would have been allowed to frequently cross enemy lines if his family remained in New Bern, but Rose Adler Prag is said to have died in New Bern on July 20, 1864.

The 1870 census finds Isaiah and Jane Prag in Calvert County, Maryland. The 1879-80 city directory of Baltimore (p. 625) lists 6 separate families of Prags, with Isaiah listed as selling furniture. The 1880 census finds him settled in Cambridge, Maryland, the seat of Dorchester County on the eastern shore of the Chesapeake Bay. This is where family records place him at the time of his death, April 18, 1889.

It appears that Isaiah and Rose Adler Prag were Jewish, and may have been one of the first Jewish families to reside in Randolph County. That may be why Isaiah gave the Steed family as valuable a gift as the ham would have been in 1864- religious dietary laws would have prevented him from eating it.

[Sources: US Census records for the years cited; Randolph County Marriage Bonds; Miscellaneous Records of the North Carolina Quartermaster’s dealings with Isaiah Prag or Pragg, preserved in the National Archives at Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, 1861-65 ; the Park Service online list of Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System, at http://www.itd.nps.gov/cwss/>; Prag family geneaology records on Ancestry.com at http://trees.ancestry.com/pt/person.aspx?pid=1078239925&tid=16758860&ssrc= .]

Paragraph 13:

“My present was a balmoral (petticoat) which she had carded, spun and woven herself…”

A Balmoral was a long woollen petticoat which was popularized by Queen Victoria at Balmoral Castle in Scotland. Usually of striped fabric, it was worn immediately beneath the dress so that it showed below the skirt.

The woman wearing a Balmoral in this “carte de visite” is Rachel Bodley (1831-1888), the first female chemistry professor at Philadelphia’s Women’s Medical College from 1865 to 1873.

Paragraph 14:

“…a bowl of mush or … plate of thick corn pones.”

Corn Meal Mush was made two different ways, and it appears that Mr. Winningham liked both of them. The first was prepared in rolls like sausage or in loaf pans like modern liver pudding. The cook would cut it in slices, dredge in egg yolk, dust in flour, fry and serve with butter, molasses, syrup or powdered sugar. The second method was to boil the corn meal in a saucepan just as if preparing raw oatmeal or grits. It was then served hot in a bowl topped with milk, sugar, fruit, raisins, nuts or ice cream.

“Corn Pone” is corn bread made without milk or eggs, and either baked in hot coals (as described by Nannie Winningham) or fried.

Modern Corn Pone Recipe (makes 4 servings):

Ingredients: 3 cups cornmeal; 3 teaspoons salt; 2-3 cups water; 3 tablespoons lard

Directions: Bring water to a boil in a medium sauce pan. Add cornmeal and salt and immediately remove from stove. Mix well. Melt half of lard in a baking pan to coat. Stir remaining lard into corn meal mixture. Pour mixture into baking pan. Bake at 350 degrees for about 50 minutes, or until golden brown.