The worst pandemic to hit the United States before COVID-19 was the “Spanish” influenza epidemic that followed the end of World War I. The parallels between that epidemic of one hundred years ago and today are striking, and show both how American society has advanced and regressed.

The worst pandemic to hit the United States before COVID-19 was the “Spanish” influenza epidemic that followed the end of World War I. The parallels between that epidemic of one hundred years ago and today are striking, and show both how American society has advanced and regressed.

Though commonly called Spanish Flu, was first widely known among the troops in Europe, and was called ‘trench fever.’ Though wartime censorship makes it hard to track, it may have been endemic to German troops on the eastern front in late 1917; in the spring of 1918 they postponed a western offensive until influenza subsided in 3rd week of March. The Kaiser himself fell ill with the flu in July, 1918. It evidently took the name “Spanish” flu because Spain was neutral in the war and had no press censorship, so the first mentions of the severity of the illness came from Spanish newspapers.

Modern studies attempting to track the spread of the virus think that it may have arrived in America via Chinese workers being sent to work on the war front in France; a “serious outbreak of pneumonia” was noted in Shantung province, on the Mongolian border in December 1917, and pandemic influenza struck Shanghai in May 1918.

An army cook at Camp Funston, Kansas is considered to have been the first U.S. influenza victim, dying in March 1918. In April 1918 the USS North Carolina docked at Norfolk, reporting 100 mild cases of the influenza.

Communicable diseases were not uncommon in one hundred years ago. Many were deadly, and most were debilitating. Before the flu arrived in the fall, there had been more than 2200 deaths in NC in 1918 from typhoid fever and tuberculosis. Older forms of influenza were seldom deadly- called “the Grippe,” it was most dangerous to the weak and elderly. North Carolina created a State Board of Health in 1877 but the first local health department was established by Guilford County in 1911.

A bulletin from the U.S. Public Health Service (The Courier, Asheboro, 10-10-18, Page1) noted that-

“Epidemics of influenza have visited this country since 1647. It is interesting to know that this first epidemic was brought here from Valencia, Spain. Since that time there have been numerous epidemics of the disease. In 1889 and 1890 an epidemic of influenza, starting somewhere in the Orient, spread first to Russia, and thence over practically the entire civilized world. Three years later there was another flare-up of the disease. Both times the epidemic spread widely over the United States.”

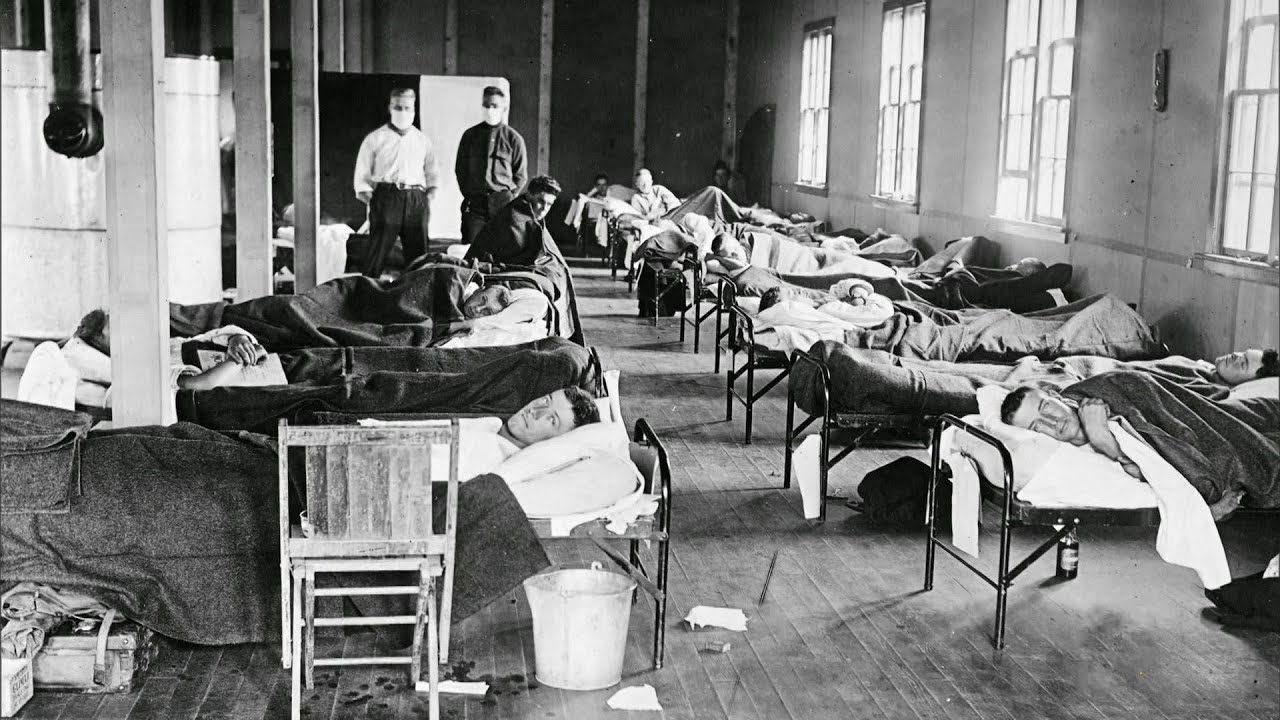

The difference with the influenza of 1917/18 (now called the Influenza A Strain) was that it triggered a virulent reaction in the immune system of those who were strongest- those twenty to forty years old, young and fit; in many cases it killed in less than 48 hours from first fever to last breath. As its victims’ lungs filled with fluid and their respiratory systems failed, their skin, starved for oxygen, turned blue- giving the tabloid headline name the “Blue Death” to the new influenza.

The difference with the influenza of 1917/18 (now called the Influenza A Strain) was that it triggered a virulent reaction in the immune system of those who were strongest- those twenty to forty years old, young and fit; in many cases it killed in less than 48 hours from first fever to last breath. As its victims’ lungs filled with fluid and their respiratory systems failed, their skin, starved for oxygen, turned blue- giving the tabloid headline name the “Blue Death” to the new influenza.

The virus came in 3 waves, the first breaking out from October 1918 to Feb 1919 and eventually spreading to every corner of the earth. A second wave occurred in the summer of 1919, and the third wave in 1920 claimed another 100 thousand. As many as 40 million people may have died and half the world’s population was infected. No vaccine was ever created, and even today no treatment would be available for this type of flu.

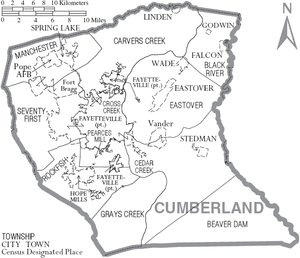

In April 1919 Dr. William Rankin, secretary of the State Board of Health, reported that more than a third of the state’s 2.5 million citizens had been infected, and 13,644 had died, including 17 doctors- 13 times the number of Tar Heels killed by the Germans in WWI.

The influenza first appeared in North Carolina in Wilmington on September 19th, 1918, and within a week it had overwhelmed that city’s hospital, considered one of the state’s best. The contagion spread West from Wilmington into the heart of the state along the railroad lines, ravaging military camps across the state.

On October 3, 1918- Governor Thomas Bickett issued statement from the Board of Health on dangers of sharing eating and drinking utensils, unrestrained sneezing or coughing; he issued an order recommending curtailing social functions and public gatherings, and proposing quarantine for those infected- they were prohibited from leaving home without a doctor’s note

Although we are missing many issues of the local newspaper for the years 1917 and 1918, the first mention of the flu from the Asheboro Courier is found on October 10, 1918, just three weeks after it was first noted in Wilmington. “Spanish influenza is rapidly spreading in this county, and the schools have all closed, as well as all other public gatherings. We think that the prohibition of the Greensboro fair was right and proper.” (Courier, 10/10/18, pg4).

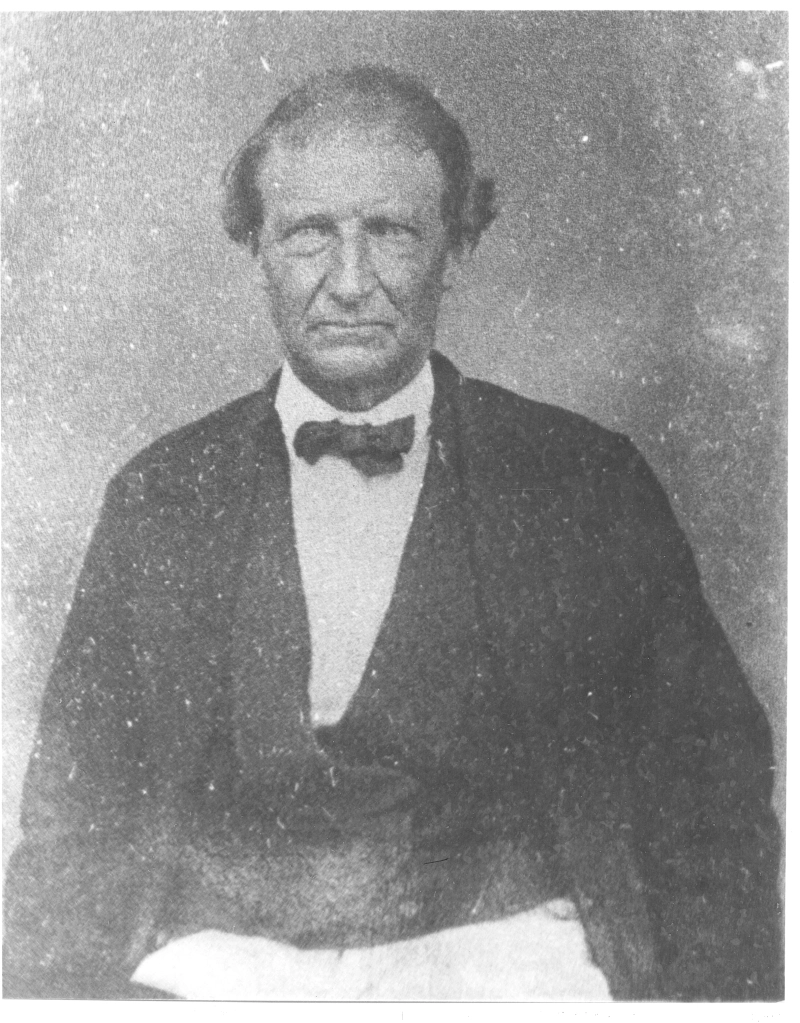

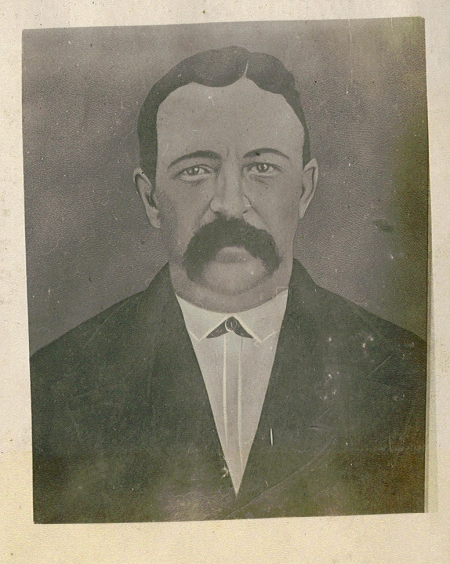

Surgeon General Blue

A interview with Surgeon General Rupert Blue (called “Uncle Sam’s Advice on the Flu”) published a week later noted- “In contrast to the outbreaks of ordinary coughs and colds, which usually occur in the cold months, epidemics of influenza may occur at any season of the year, thus the present epidemic raged most intensely in Europe in May, June and July….

“In most cases a person taken sick with influenza feels sick rather suddenly. He feels weak, has pains in the eyes, ears, head on back, and may be sore all over. Many patients feel dizzy, some vomit. Most of the patients complain of feeling chilly, and with this comes a fever in which the temperature rises to 100 to 104. In most cases the pulse remains relatively slow.

“In appearance one is struck by the fact that the patient looks sick. His eyes and the inner side of his eyelids may be slightly “bloodshot” or “congested,” as the doctors say. There may be running from the nose, or there may be some cough. These signs of a cold may not be marked; nevertheless, the patient looks, and feels very sick….

“In appearance one is struck by the fact that the patient looks sick. His eyes and the inner side of his eyelids may be slightly “bloodshot” or “congested,” as the doctors say. There may be running from the nose, or there may be some cough. These signs of a cold may not be marked; nevertheless, the patient looks, and feels very sick….

“No matter what particular kind of germ causes the epidemic, it is now believed that influenza is always spread from person to person, the germs bring carried with the air along the very small droplets of mucus, expelled by coughing or sneezing, forceful talking, and the like by one who already has the germs of the disease. They may also be carried about in the air in the form of dust coming from dried mucus, coughing or sneezing, or from careless people who spit on the floor or on the sidewalk.” (The Courier, Asheboro, 17 Oct 1918, p6)

Rupert Blue

An interesting sidelight is that Surgeon General Rupert Blue was a native of Rockingham, in Richmond County, North Carolina. Blue (1868-1948) entered the US public health service in 1892, and made a name for himself coordinating the federal response (yes, there was one even back then) to the San Francisco bubonic plague outbreaks of 1900-1904, and again after the earthquake of 1906. He was also involved in efforts to control yellow fever in New Orleans in 1905. He was appointed Surgeon General by President Taft in 1912 and served until March 1920, and oversaw the dramatic expansion of US public health services during WWI. The U.S. Hygenic Laboratory which Blue established created vaccines against tetanus, diphtheria, typhoid and smallpox, and after the war, laid the foundation for the creation of Veterans’ Administration hospitals and clinics. So it is no exaggeration to say that the foundation of our modern health care system was put in place by Surgeon General Blue. [And I might interject, that he is probably some kind of relative of my father’s mother, whose maternal grandfather was Evander McNair Blue of Moore County.]

Back on the home front, the Randolph County Board of Health took decisive action based on years of knowing what had worked to stem the spread of incurable communicable diseases. Schools were closed. Both live and moving picture theaters were closed. There were no bars, as prohibition had ended alcohol sales, and there were few restaurants, as most people cooked at home. The Randleman Chrysanthemum Show was cancelled. Joel Trogdon, minister of Charlotte Methodist Church, announced that the Richland Circuit quarterly conference was cancelled, as well as the associated preaching services. He rescheduled for the next month, “we hope influenza will be subsided by this time, if not perhaps we can hold our meeting out of doors.” (Courier, 24 Oct 1918 p5)

In Asheboro, “The influenza situation in Asheboro has greatly improved over what it was last week. The people have been using precautions and should continue to do so…. Much anxiety is felt in Asheboro and Randolph County for the Randolph boys in France and especially for those in the Thirtieth Division, as they have evidently been in the thick of the fighting during the recent battles. One boy has written that he has been in the trenches sixteen days at a time.” (id)

In Trinity, “Trinity High School has suspended on account of Spanish influenza. Some of the older people say, this is the first time the doors of Trinity has been closed in October for over 70 years. In other words, the school has been in progress here for 70 years, probably a little longer. The doors were not closed during the Civil War.” (id)

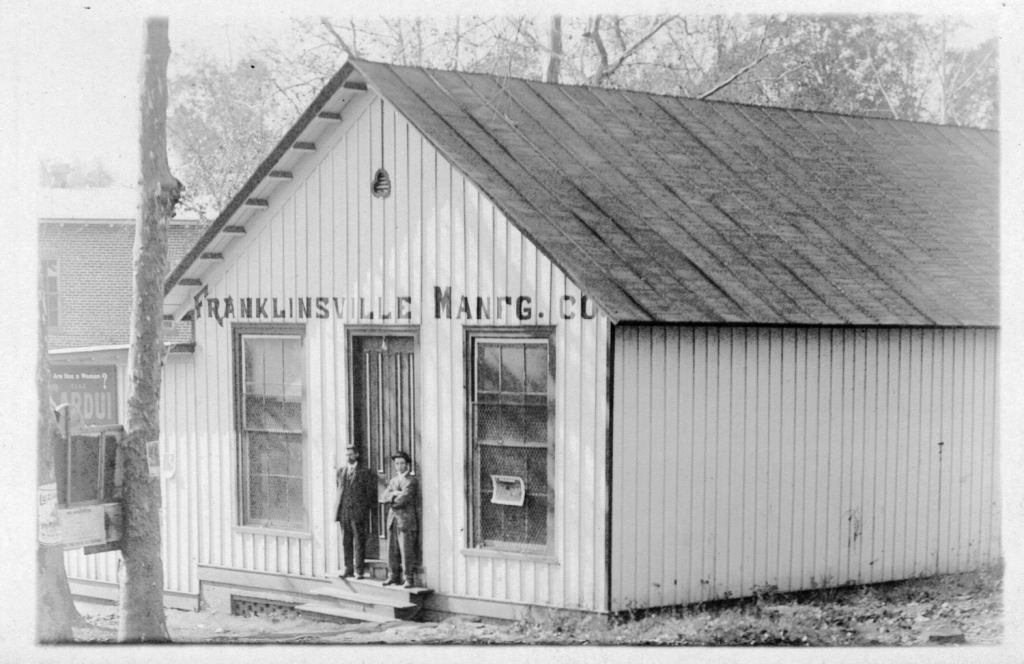

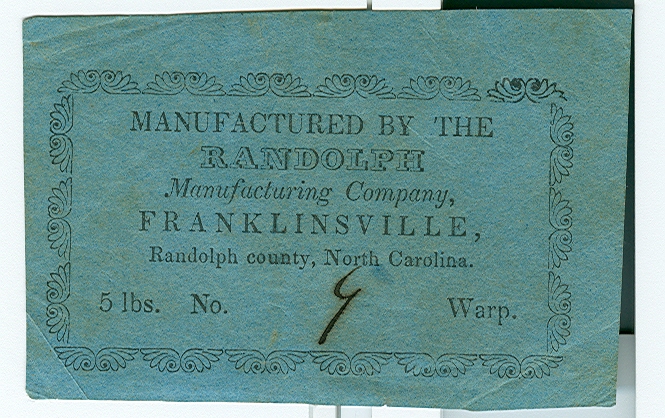

And in Franklinville, the war also precluded too much worry about the flu: “The last report of all Spanish influenza cases in the community are on the mend, and it is not expected that any cases will prove fatal…. Our farmers are busy gathering and husking corn, and preparing to sow a large crop of wheat this fall and are doing all they can to help our boys push their way to Berlin.” (id)

But the same edition of the paper showed that local people were dying.

But the same edition of the paper showed that local people were dying.

“Private A.M. Phillips died at Camp Joseph E. Johnson, Jacksonville, Florida, last Tuesday morning at ten o’clock from pneumonia following an attack of influenza. The deceased had been ill about two weeks. The fact that he had suffered from four previous attacks of pneumonia probably made it harder for him to combat the disease. Mrs. Phillips and Miss Kate Phillips were with the husband and brother when the end came. The body is expected today, after which the funeral will follow. Private Phillips went to Camp Hancock, Augusta, Ga, July 26, last, with an increment of Randolph men, and was later transferred to Camp Johnson. He was at home on furlough just a few weeks ago.

The deceased is survived by his parents, Mr. and Mrs L. C. Phillips, Asheboro; one brother, Mr. Hal Phillips. Asheboro: and four sisters, Mrs. Walter Davis, Randleman Route; and Misses Kate, Lizzie and Alice Phillips, Asheboro; besides his wife, who was Miss Erma Lynch, of Asheboro Route 1, and to whom he was married about six mouths aero. A large circle of friends throughout the county sympathize with the bereaved family.”

And-

“Mr. Gurney Davidson died at his home west of town last Thursday from pneumonia following an attack of Spanish influenza. The burial was at West Bend church the following day… Mrs. Gurney Davidson died in the evening of the same day her husband was buried from the same fatal disease, and was laid to rest at West Bend on Saturday… Mr. Davidson was about 35 years of age… Three small children, the oldest only six years of age, are left orphans by these deaths.”

A week later, the headline was that flu had claimed the President of the University of North Carolina.

Dr. Edward Kidder Graham, eighth president of the University of North Carolina, and a prominent educational figure in the nation, died last Saturday night at his home, Chapel Hill, from pneumonia following an attack of Spanish influenza. Dr. Graham had been ill less than a week, the disease assuming the most malignant type and turning to the dread pneumonia in two or three days. The funeral was held at Chapel Hill, Monday afternoon. There was no service at the church or home, but a simple service at the grave… All work at the University was suspended for the day and the faculty and students attended the funeral in a body. [The Courier, 10-31-18, p7. Marvin Hendrix Stacy, the chairman of the faculty, became the acting university president after Graham’s death. On 21 January 1919, Stacy also died from influenza. [https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/exhibits/show/going-viral/unc ]

Dr. Edward Kidder Graham, eighth president of the University of North Carolina, and a prominent educational figure in the nation, died last Saturday night at his home, Chapel Hill, from pneumonia following an attack of Spanish influenza. Dr. Graham had been ill less than a week, the disease assuming the most malignant type and turning to the dread pneumonia in two or three days. The funeral was held at Chapel Hill, Monday afternoon. There was no service at the church or home, but a simple service at the grave… All work at the University was suspended for the day and the faculty and students attended the funeral in a body. [The Courier, 10-31-18, p7. Marvin Hendrix Stacy, the chairman of the faculty, became the acting university president after Graham’s death. On 21 January 1919, Stacy also died from influenza. [https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/exhibits/show/going-viral/unc ]

On October 31, the State Board of Public Health reported that “Taking the State as a whole, the influenza situation is looking better, the reports showing marked improvement in a number of towns. On the basis of imperfect reports, it is estimated that the number of cases in North Carolina, dating from the first outbreak in Wilmington, will pass a quarter of a million before it runs its course. The death rate in Raleigh so far has been about three per cent of the cases, as estimated, and on such a basis the ravages of the disease will kill 7,600 North Carolinians.”

But the end of the war brought a setback. Social distancing restrictions were loosened following Armistice Day, with unintended complications. By the end of the month, T. Fletcher Bulla, the Secretary of the Board of Health, put even more restrictions were in place.

“On account of the influenza situation and the danger of spreading the disease, the County Board of Health has decided it is inadvisable to hold the regular term of court for the county scheduled to begin December 6th. After a conference with local officials, the members of the local bar, and Judge Long, I am directed to say that the term has been called off. Parties, witnesses and jurors are all hereby notified that they need not come.” [The Courier, 11-28-18, pg5].

“Ramseur has been struck with influenza the past two weeks. Over two hundred cases have been reported, with three fatalities. We hope the worst is behind us now. It seems to be abating but we find this is a very subtle thing, it come unawares and spreads like fire. Let us be as careful as we possibly can lest it takes a heavy toll from us yet.” [The Courier, 12-12-18, pg1].

In January 1919 the Courier reported that it was unable to print the newspaper on schedule.

“INFLUENZA RAGING IN ASHEBORO ATTACKS COURIER FORCE. During the past few days many people of the town have been stricken with influenza, few homes having every person confined to bed. The disease seems in lighter form than it did during the first epidemic which was visited upon the town during the first of November. The Courier force has been so afflicted, having three members out, that we are unable to appear in usual form. We feel that our readers will understand the unfortunate situation. It is under difficulties that we appear at all. We hope’ next week to make our usual appearance.”[The Courier, Jan. 16, 1919, pg1]. Neither of the paper’s linotype operators, L.B. Lambert and C.L. Scott, had fully recovered by February 6th.

The second wave of flu had disappated by May, 1919, but then reappeared full blast in the winter of 1920. “For more than two weeks the epidemic of influenza has been in full blast at Coleridge. Practically everybody in the town has had it, there being more than 250 cases. Up to date only two deaths have occurred, that of Mrs. L. B. Davis, and Mrs. A.M. Poole. Mrs. Davis died the latter part of last week. She was 35 years of age, and a daughter of the late Gurney Cox. At the time of Mrs. Davis’ death her husband was seriously ill with influenza. Mrs. A.M. Poole was a daughter of Mr. W.A. Poole, of Coleridge. She is survived by her husband and three children.” [The Courier, 5 Feb 1920, pg1.]

The second wave of flu had disappated by May, 1919, but then reappeared full blast in the winter of 1920. “For more than two weeks the epidemic of influenza has been in full blast at Coleridge. Practically everybody in the town has had it, there being more than 250 cases. Up to date only two deaths have occurred, that of Mrs. L. B. Davis, and Mrs. A.M. Poole. Mrs. Davis died the latter part of last week. She was 35 years of age, and a daughter of the late Gurney Cox. At the time of Mrs. Davis’ death her husband was seriously ill with influenza. Mrs. A.M. Poole was a daughter of Mr. W.A. Poole, of Coleridge. She is survived by her husband and three children.” [The Courier, 5 Feb 1920, pg1.]

When the Randolph County Board of Health met in February 1920 “a number of schools, churches and Sunday schools of the county were closed on account of the prevalence of influenza. Among the schools that have closed are: Coleridge, Pleasant Grove, Brower, Richland, Grant, Columbia and Tabernacle townships, also Miller’s school and Wheatmore school in Trinity township and Central Falls school in Franklinville township. It was further ordered that the stores in the county be closed at 7 o’clock p.m. and unnecessary congregating in cafes, barber shops and other public places be prohibited. It was also ordered that all moving picture shows of the county be closed for a period of two weeks. Another order was that all the children in a family where there is a case of influenza be kept out of school for two weeks. The matter of losing other schools in the county and taking further precaution to prevent the spread of influenza was left in the hands of Messrs. W.L. Ward, T.F Bulla and Dr. C. A. Hayworth, who were authorized to take any steps that they deemed wise without consulting the county board of health further.”

In late March, one of Asheboro’s best known citizens died of the flu. “The news of the almost sudden death of Capt. A.E. Burns at his home in Asheboro on Wednesday of last week was a distinct shock to his many friends in Randolph County. Capt. Burns had influenza but was improving and at the time the call came he was sitting up in bed, talking to some friends, assuring them he would be out in a few days…. Mr. Burns was the son of B.B. and Fannie Moss Burns. He was born in Asheboro and has spent his life here, consequently was known by every body- to his old friends he was known as “Eck Burns”… At the age of eighteen years Mr. Burns went in the employ of Southern Railway and came in to Asheboro on the first train as baggage master. Twenty five years ago he was promoted to conductor and has served the railroad in that until his death… “ [The Courier, 25 March 1920, p1]

During the 1920 epidemic, the Fletcher Bulla recommended 9 suggestions for good public health. Some show that some major improvements have occurred in a century-

During the 1920 epidemic, the Fletcher Bulla recommended 9 suggestions for good public health. Some show that some major improvements have occurred in a century-

“Don’t use public drinking cups that have not been properly sterilized. Every school child should carry an individual cup… while at school.”

Others would be familiar today, human nature having not changed that much-

“Avoid coughing, if you must cough or sneezing, place a handkerchief over your mouth.

“If you go into a room where any patient is confined with … gripe or colds, use a mask or handkerchief over your mouth and nose and wash your hands if you have touched the patient, bedding or other furniture in the room.

“Promiscuous kissing should be avoided.”

*Final note: I know of no official statistics for the number of Randolph County citizens who died during the Spanish Flu pandemic. Because of wartime censorship, the figures that might have been available were not published, and because of the lack of testing and treatment facilities, the number was probably much higher than was known at the time. Some day perhaps, a comprehensive review of death certificates might give us a ball park figure. But the number was shockingly large, even to a generation used to sudden death and incurable disease.

For more information on the 1918 pandemic, see the following excellent sources:

Cockrell, David. 1996. “A Blessing in disguise’: The influenza pandemic of 1918 and North Carolina’s medical and public health communities.” NCHistRev 73 (3) 309-327

Pettit, Dorothy Ann. 1976. “A Cruel Wind: America Experiences Pandemic Influenza, 1918-1920. A Social History. Univ. New Hampshire PhD Diss., 1145.

The worst pandemic to hit the United States before COVID-19 was the “Spanish” influenza epidemic that followed the end of World War I. The parallels between that epidemic of one hundred years ago and today are striking, and show both how American society has advanced and regressed.

The worst pandemic to hit the United States before COVID-19 was the “Spanish” influenza epidemic that followed the end of World War I. The parallels between that epidemic of one hundred years ago and today are striking, and show both how American society has advanced and regressed.

The difference with the influenza of 1917/18 (now called the Influenza A Strain) was that it triggered a virulent reaction in the immune system of those who were strongest- those twenty to forty years old, young and fit; in many cases it killed in less than 48 hours from first fever to last breath. As its victims’ lungs filled with fluid and their respiratory systems failed, their skin, starved for oxygen, turned blue- giving the tabloid headline name the “Blue Death” to the new influenza.

The difference with the influenza of 1917/18 (now called the Influenza A Strain) was that it triggered a virulent reaction in the immune system of those who were strongest- those twenty to forty years old, young and fit; in many cases it killed in less than 48 hours from first fever to last breath. As its victims’ lungs filled with fluid and their respiratory systems failed, their skin, starved for oxygen, turned blue- giving the tabloid headline name the “Blue Death” to the new influenza.

“In appearance one is struck by the fact that the patient looks sick. His eyes and the inner side of his eyelids may be slightly “bloodshot” or “congested,” as the doctors say. There may be running from the nose, or there may be some cough. These signs of a cold may not be marked; nevertheless, the patient looks, and feels very sick….

“In appearance one is struck by the fact that the patient looks sick. His eyes and the inner side of his eyelids may be slightly “bloodshot” or “congested,” as the doctors say. There may be running from the nose, or there may be some cough. These signs of a cold may not be marked; nevertheless, the patient looks, and feels very sick….

But the same edition of the paper showed that local people were dying.

But the same edition of the paper showed that local people were dying. Dr. Edward Kidder Graham, eighth president of the University of North Carolina, and a prominent educational figure in the nation, died last Saturday night at his home, Chapel Hill, from pneumonia following an attack of Spanish influenza. Dr. Graham had been ill less than a week, the disease assuming the most malignant type and turning to the dread pneumonia in two or three days. The funeral was held at Chapel Hill, Monday afternoon. There was no service at the church or home, but a simple service at the grave… All work at the University was suspended for the day and the faculty and students attended the funeral in a body. [The Courier, 10-31-18, p7. Marvin Hendrix Stacy, the chairman of the faculty, became the acting university president after Graham’s death. On 21 January 1919, Stacy also

Dr. Edward Kidder Graham, eighth president of the University of North Carolina, and a prominent educational figure in the nation, died last Saturday night at his home, Chapel Hill, from pneumonia following an attack of Spanish influenza. Dr. Graham had been ill less than a week, the disease assuming the most malignant type and turning to the dread pneumonia in two or three days. The funeral was held at Chapel Hill, Monday afternoon. There was no service at the church or home, but a simple service at the grave… All work at the University was suspended for the day and the faculty and students attended the funeral in a body. [The Courier, 10-31-18, p7. Marvin Hendrix Stacy, the chairman of the faculty, became the acting university president after Graham’s death. On 21 January 1919, Stacy also

The second wave of flu had disappated by May, 1919, but then reappeared full blast in the winter of 1920. “For more than two weeks the epidemic of influenza has been in full blast at Coleridge. Practically everybody in the town has had it, there being more than 250 cases. Up to date only two deaths have occurred, that of Mrs. L. B. Davis, and Mrs. A.M. Poole. Mrs. Davis died the latter part of last week. She was 35 years of age, and a daughter of the late Gurney Cox. At the time of Mrs. Davis’ death her husband was seriously ill with influenza. Mrs. A.M. Poole was a daughter of Mr. W.A. Poole, of Coleridge. She is survived by her husband and three children.” [The Courier, 5 Feb 1920, pg1.]

The second wave of flu had disappated by May, 1919, but then reappeared full blast in the winter of 1920. “For more than two weeks the epidemic of influenza has been in full blast at Coleridge. Practically everybody in the town has had it, there being more than 250 cases. Up to date only two deaths have occurred, that of Mrs. L. B. Davis, and Mrs. A.M. Poole. Mrs. Davis died the latter part of last week. She was 35 years of age, and a daughter of the late Gurney Cox. At the time of Mrs. Davis’ death her husband was seriously ill with influenza. Mrs. A.M. Poole was a daughter of Mr. W.A. Poole, of Coleridge. She is survived by her husband and three children.” [The Courier, 5 Feb 1920, pg1.] During the 1920 epidemic, the Fletcher Bulla recommended 9 suggestions for good public health. Some show that some major improvements have occurred in a century-

During the 1920 epidemic, the Fletcher Bulla recommended 9 suggestions for good public health. Some show that some major improvements have occurred in a century-

I am writing this from my home in Franklinville, NC, in the midst of COVID-19 self-isolation. For most of America, home isolation is designed to “flatten the curve”- to impose community isolation measures that slow the spread of infection and keep the daily case load at a manageable level for our existing health care resources. In my case, it’s to protect me in the wake of my recent heart surgery, and keep me from the risk of pneumonia on top of asthma and post-anesthesia breathing issues.

I am writing this from my home in Franklinville, NC, in the midst of COVID-19 self-isolation. For most of America, home isolation is designed to “flatten the curve”- to impose community isolation measures that slow the spread of infection and keep the daily case load at a manageable level for our existing health care resources. In my case, it’s to protect me in the wake of my recent heart surgery, and keep me from the risk of pneumonia on top of asthma and post-anesthesia breathing issues.

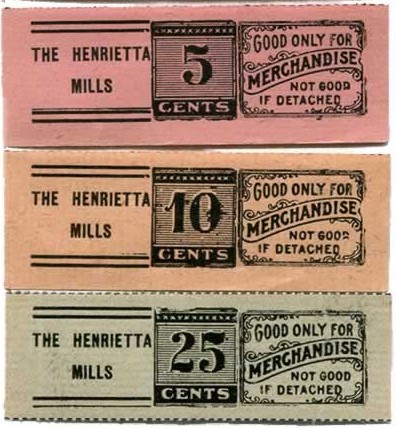

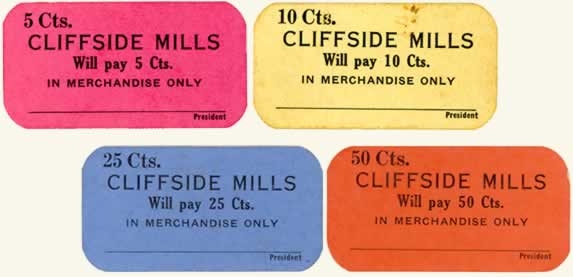

Miss Kitty Caviness, a retired teacher, first told me about Franklinville Pest House, which was in the hollow between her house and the Lower Mill. It was a small cabin or “fever shed” with beds, and if the illness was something that could endanger the whole village, the patient was taken there under quarantine. I never saw the building; as far as anyone could remember, the Franklinville Pest House was last used during the “Spanish Flu” epidemic of 1918-1920. “It smelled like sulpher,” said Miss Caviness, and undoubtedly this was due to the common practice of the time of disinfecting the air by burning sulpher in open pans in each room.

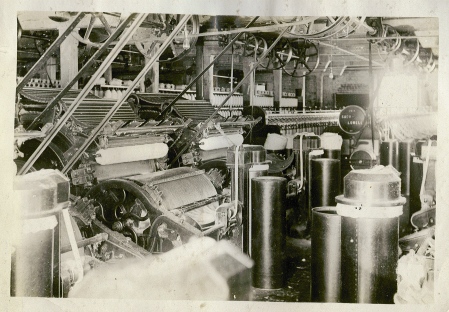

Miss Kitty Caviness, a retired teacher, first told me about Franklinville Pest House, which was in the hollow between her house and the Lower Mill. It was a small cabin or “fever shed” with beds, and if the illness was something that could endanger the whole village, the patient was taken there under quarantine. I never saw the building; as far as anyone could remember, the Franklinville Pest House was last used during the “Spanish Flu” epidemic of 1918-1920. “It smelled like sulpher,” said Miss Caviness, and undoubtedly this was due to the common practice of the time of disinfecting the air by burning sulpher in open pans in each room. I’m told that Randleman also had a Pest House, perhaps shared with Worthville, and this may have been a feature of all the Deep River Mill villages. Universal vaccination for communicable deadly diseases gradually did away with the need to isolate patients from their neighbors, but the sudden rise of the “Spanish Flu” in 1918 brought them back into wide use for a few years- and triggered a movement to build community hospitals in rural areas.

I’m told that Randleman also had a Pest House, perhaps shared with Worthville, and this may have been a feature of all the Deep River Mill villages. Universal vaccination for communicable deadly diseases gradually did away with the need to isolate patients from their neighbors, but the sudden rise of the “Spanish Flu” in 1918 brought them back into wide use for a few years- and triggered a movement to build community hospitals in rural areas.