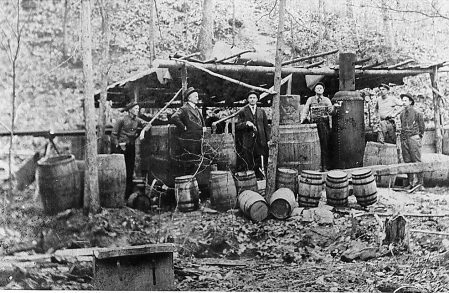

Ready to Run the Blockade, from http://www.louisville.com

This is about half of an oral history interview I recorded with Dove Coble (1900-2000) at his daughter’s house on 1 March 1997. Dove was a delightful fellow who remembered just about everything that had ever happened to him. I had a great time talking with him, and it was the only interview I ever did with someone willing to talk about the business of running moonshine, a big part of the economy of the county in the late Nineteenth and the first half of the Twentieth centuries.

The long and colorful tradition of moonshining in Randolph County ran from Black Ankle on the Montgomery County border, through Seagrove and Millboro all the way north to Level Cross. After the Civil War the federal government established a system of licensed distilleries in which Treasury Agents would collect a tax on each gallon of whiskey produced. There were many “Government Stills” established across Randolph, but for each legal still there were at least two illegal producers. Moonshiners refused to run a “government still” and pay the excise tax. In Prohibition days (and afterwards) running the illicit liquor from the stills deep in the Randolph County countryside up to the thirsty markets in the North was a major source of cash income. Though glass “Mason” jars were invented before the Civil War (many were produced up into the 1900s with the mark “Patent Nov 30th 1858”), moonshiners kept many a Randolph and Moore county potter in business up until World War II. And transporting those containers to the ultimate buyers was the province of the “Blockade Runner,” or “Blockaders,” a very conscious reference to the Civil War “greyhounds of the sea” which ran the federal blockade of southern ports to supply the Confederate war effort.

Dove Coble died just a few weeks short of his 100th birthday, and was buried in Gray’s Chapel, or “York Town,” as he called it.

My name’s William Dove Coble. Senior. That’s my boy at Eastern Randolph [his son, Dove Coble Jr., was a teacher at ERHS]. I was born the 11th of June, 1900. If I live to see June I’ll be 97. I was born over there on Sandy Creek; Brower’s Mill. It’s Kidd’s Mill now, on Sandy Creek, back in the woods there. My daddy, Rossie Coble, died in 1917, and was buried over at Gray’s Chapel, and I’ve been there ever since. There was five of us boys and three girls. I was the oldest child. They’ve all gone but me and my youngest brother, Truman Coble, lives there in Ramseur. Seventeen years younger than me. My daddy died in March, and in June I was seventeen, and then Truman was born after that. My father lived in the country. Shelly Coble was my daddy’s brother, and Will Coble, and Clem Coble, they’re buried this side of Town, there where Joe Buie’s father is buried. Charlie Coble and Ham Coble, they’re my closest kin. I lived over here at Gray’s Chapel, not at the schoolhouse, but on up the road where that dairy barn is, at the rock wall. Hackett Road. That’s where Dove Jr. lives. My wife passed away and I’ve been over here at Opal’s [his daughter in Asheboro] since ’82, when Curtis Coble passed away….

I never did get no education, never got to seventh grade. I get more now out of the Upper Room than I can the Bible. The stories, you know; I ain’t got no education. I can read, and write my name. I started off at Patterson’s Grove. The schoolhouse was on what you called the Ferguson road, the road from Ramseur to White’s Chapel. I went there four years, and then over to White’s Chapel, at a little schoolhouse there, didn’t go there but one. Just five or six years. I moved all over the country. I wasn’t doing nothing but running around. We just drug up, to tell the truth about it. I’m lucky to be here. I lost my daddy, and I wasn’t 17; there was nine of us, and no welfare nor nothing. It was Hoover days. Can you imagine how I lived? Just drug up.

I lived over there in the country when the war ended, close to Brower’s Mill. My daddy died in 1916, and the next year I had to register. I was up plowing corn there in the back yard, plowing around saw logs in the field. Momma come out in the field and waved at me; we heared the bells and whistles blowing at Franklinville. We didn’t have any telephones. They tied them whistles down; you can imagine the racket. Both mills sounded the same; they both had whistles; you couldn’t tell one from the other. I registered for the war in Ramseur. I.F. Craven ran the draft board. He lived in a big house behind the drug store beside Fred Thomas, who run the broom shop. I’ve got that little card; it’s the only thing I’ve got to know when I was born; didn’t get no birth certificate.

My grandpaw W.H. Coble, William, is buried right there in that old cemetery, Old Salem. I never remember any church there, I don’t know where it fell down or what. He’s where the William come from. Leeshy, my grandmaw, that’s where they got the Dove; from Dunc Dove’s crowd; my grandmaw was his sister. They lived up towards White’s Memorial. Dunc and his son Tracy lived there on the hill next to Dr. Fox, on that street above Burnice Jones. My grandpaw come down on a wagon and we went to that old wooden store [the lower company store]; went and got molasses out of a fifty-gallon drum with my grandpaw. That was back before I went to school, Nineteen Five. The Company stores were just old country stores. They had everything in the world you wanted in there. But I didn’t buy nothing. Didn’t have to buy nothing. Wasn’t nothing I could buy. I didn’t have no money; what could I buy?

1924 Open Cab Express Body Model TT- Ford’s first pickup. Before that model year Ford only provided the truck chassis, and local wagonmakers purpose-built the bodies.

I come there to Franklinville in Twenty. Ed Routh, Ernest’s daddy, and Paul, and Iula, found out I needed work. I drove a truck, the first one they ever had in Franklinville. One ton Ford truck, open bed, to haul flour and feed and everything they made. Had a cover for it, but it was open, open bed. Open cab, no glass. I hauled flour to Seagrove and Siler City, and loaded it on the train. They shipped it to the college up there. Women’s College bought the flour direct from the mill, and had it shipped up there. It was too far to drive then. Wasn’t no such thing as a hard surface. 64 wasn’t built. No road down to Ramseur, or anywhere. Did without ‘em. Parks Buie told me that Joe would order five gallons of oysters of a morning, tell them to put them on the train down on the coast, and they’d come to Greensboro and down to Franklinville on the second train, that run after dinner, and he’d get it of an evening. Five gallons of oysters for a dollar and a quarter. The train went up in the morning, met the trains and stuff in Greensboro, and come back after dinner.

Guess how much I made in six days. Ten dollars a week for six days, ten hours a day. All day. Went in six in the morning, stayed till five in the evening. An hour out for dinner. If they didn’t fix for me I walked back to the house for dinner, next door to Burnice Jones, where he lives now. That house above it. I lived with my great aunts, Bell and Lizzie and Effie Luther. They’re all buried around there. They worked in the mill before I went down there. My aunts were fine people, but they was old then. They was retired. Two of them never married. Old widow women. They looked after me, they was good. I maybe paid $5 a week; if I wanted to pay them anything I did, but I didn’t have to.

Ed Routh was the head knocker and manager. He was the flour man. Bascom Kinney ground the corn meal. Old Davis, across the river, he was there part of the time. They’re all gone. They bought the truck while I was there. I was the first driver they had, anyway. I could drive anything then. The first job I had, I helped put flour in the sacks, meal, flour and everything. Corn meal went in little bitty bags, ten pounds. Plain corn meal. They didn’t have no self-rising to start with; they put it in after I went down there. Excelsior was the plain flour; Dainty Biscuit was the self-rising. I bagged that flour, and Ernest helped before he went on the road. Ten pound bags; twenty-five; and them big bags is what they shipped. They put ninety-eight pounds in them. The college got maybe ten bags in a shipment, every week, or whenever they needed it. I first hauled stuff through the wooden bridge, the covered bridge. Mr. Routh lived right up there by the mill. Basc Kinney lived next door, that worked for Ed as a miller.…

[I] Went to work in the roller mill. Me and Ernest worked there, and his daddy. Ed Routh done the most of the work. He could do most anything, kept everything just as clean as a woman. He kept us wore plumb out to keep the spider webs and things cleaned up. That mill, it run by water then. The water wheel was in the lower end, the back end. The race run around behind the mill, and a chute come out of there, going under to the water wheel, and the shaft run back under the mill and the belts went on up. All of it was ground by water then. Didn’t have no lights to start with; they finally got up to date, and got electricity. And the cotton mill run by water then, too….

I had an old T-model, $150 copper head T-model, ‘Fifteen. I got Joe Buie to let me have a little money, maybe a hundred dollars, and my aunt give me some. There wasn’t no bank, they put that in after I went there. That store opened up, and the office for both mills. I didn’t have to have but two or three hundred dollars, but I didn’t have none. I got it the first year I was down there. Twenty-one. $150; drove it; kept it for five years, and I got that much out of it when I sold it. Then when the A-Models come out, I got another one. I had a A-Model when I got married….

[John] Clark changed everything [about Franklinsville in 1923]. But of course I was blockade running around all over the country, wasn’t married or nothing; didn’t stay down there much. I was maybe in Siler City one night and somewheres else the next. But I still worked every day, ten hours a day. Back then, the hours weren’t nothing. Bob Craven, who lived in that last house by the trussell, said he could remember me going by there of a morning at daylight, going to the mill. He said, “You was crazy as hell, then.” I said, I didn’t have no choice. I stayed at home there, piddled around so we didn’t starve. You know what we had. Just nothing. Hoover Days. I don’t care what your politics are. If you lived through Hoover Days, you won’t forget it, if you live to be a hundred. I sold liquor of a night, when I was driving the truck [for the roller mill]; me and Benton Moon. Did you know him? Fanny Burke was his wife, and Roy Holliday married her later. Me and Benton would go over in York Town and get a case every night. All of them around there, Doc Cheek, that run the drugstore, he’d drink it just like water. That’s what Franklinville was like when I went down there.

You could buy liquor anywhere you wanted it. There were a few government stills around, but I never did go to none of them. Over here in Lineberry where I live now, George Allred had one back up in the woods there. And there was one there at Shady Grove. Sharp Kivett, he’d give you the history of that. Fletcher Pugh, owns that sawmill on that road, he could tell you the truth about it. Sharp Kivett and George Allred, that’s the only two government-mades I ever went to, knew where the places were.

But I went to all these others, all over the country. We had plenty of it around White’s Chapel. York Town, or White’s Chapel, it’s all the same to me. People there made blockade whiskey, it wasn’t government liquor. My daddy made liquor all his life. Old man Warren Langley over here at Staley, down close to the government still at Staley; his boy Clarence died here last year; Warren Langley was number one. The Toomeses were good up in Level Cross. But if you wanted good liquor, back in below Seagrove, down towards the river, old man Lucas was the one. Cross the railroad and go back down there by Luck’s, and wind around not more than a mile back over in there. If he had bad liquor he’d tell you so. He’d say, “I ain’t got nothing for you this week.” I wouldn’t buy no burnt liquor. And he

had enough sense, if had a little burnt liquor, he wouldn’t put it off on one of his customers. You know, the mash, what makes the steam off the whiskey, if it stuck to the bottom of your still, it burnt. It ain’t nothing to brag about, but they’d take me when I was little, and they’d poke me there after the fire was took out, and have me clean that still out. I’ve been in one many a time. If you make it right, you had copper from where you put it in the still. Then it went to the wooden doubler, and then it went up in the cooler, and when it went on out down there where you catch it in a jug, it was liquor. If it come out there, and there weren’t no bead on it, they wouldn’t save it. You’d check the temperature by looking to see if it beaded up on the copper. You’d shake it. If it’s right fine on you, it ain’t rig

ht. It all used to be made out of corn; they made out of sugar later. That man in Staley, to start off with, he wouldn’t have no sugar liquor. He made corn liquor. Oscar Langley was one of Warren’s boys. He used to play ball in Ramseur and he was drunk as a fool, and they couldn’t tell it. He was a pitcher, I believe. It’s all behind me, but I’ve seen lots of things in my time. There ain’t a place between here and Staley, creek or branch or road nor nothing else that I ain’t been. I’ve been down to a still on that Hickory Mountain road, from Siler City to Pittsboro. It ain’t nothing to brag about, but I’ve been there. It was the way to make money. But I didn’t drink none of it. I found out, it was to sell, not to drink. I’ve never been drunk in my life. My brother, he took enough for me and him both. It just ruint him. But you can’t convince him of that, even now.

Not many people would fool with brandy. Some of them made it, and some didn’t. I had the most brandy that’s ever been over in there. I had twenty gallons up there in Lineberry, in the barn. Clark Millikan made it for me, the first brandy he ever made in his life. That was R.C. Millikan, who died here recently. I went to the mountains and got a whole load of apples, put it in the barrell, and kept it till it worked over. Made cider. Put them in a barrell, put your sugar in it, or after it sours you can make it without if you clear it up. While it’s working you can’t still it. It’s got to work over. Clark made a little money. But he died over here with his britches open [in the nursing home], just like me and you’s gonna do.

I could make $10 in a night. That’s the reason I went home; I told Ed Routh I could make more than that by going to York Town one day a week. Well, he said, you just come on and work for me while you’re here, and I’ll pay you as much again as you’re getting. They paid me five out of the mill and five out of the Company. It all went to different names. Roller mill got credit for this; the mill got the other. I still run around everywhere, but he didn’t know it. I didn’t ever fool with it around there [the roller mill]. Ed would take a drink, but I didn’t know till after he was Register of Deeds that he ever did. He wasn’t a drunkard, but after he’d come back to Ramseur, he told me, when you get some good, you can bring me half a gallon once in a while. But politics didn’t change that man. He didn’t change because he had an office job. If you’d started down there where I did, barefooted, no daddy, you’d know about how you’d feel. Then when you’d get up a little, you’d get above it. But Ed was number one, and Joe Buie was just as good. He wouldn’t tell you no lie, nor cheat you either. And that old Spoon boy, one armed man, the banker there, run the bank beside the office; if I didn’t have a dollar I could go in there and get it. The Sumners lived in that house across the road. John, and George, the county doctor. And two girls. Dave Sumner let me put my new car in that shed behind the house, wouldn’t charge me a cent. Edison Curtis lived up on that hill on Depot Street, and Henry Curtis, and Polly Newsom, and Will Thomas lived down through there. There wasn’t anybody in Franklinville or between here and Staley I didn’t know.

Sometimes you’d pay $5 for six gallons; you’d take it and peddle it out; people would buy it, and you could double it. I took it right down town there [Asheboro], where the bank used to be [Bank of Randolph], and people would give me orders to take some to Greensboro. They couldn’t get blockade liquor in Greensboro. They had to come out somewhere else and get it. They could buy liquor, but they didn’t want that. That man at the bank would say, “You go take Ben Cone five gallons. He lives out there toward White Oak. Just drive on out there like you own the place. Drive in there like you have groceries.” I had pretty good nerve then. But they never caught me. Tommy Brookshire that lived at Randleman was the deputy here one time. I was going to town one night, right down here where the hospital is; I was in one of those A models. Well, he just drove up to me and was gonna stop me, and I just turned round and went down that side street, and didn’t see him any more that night. And he didn’t see me. That’s as close as anybody ever caught me, but I didn’t stop. Them days is all gone.

I stayed there till the last day of Twenty-five. Got married, and never did work any more down there. I moved up here to Lineberry, Acie’s Store up above Gray’s Chapel. I didn’t have no land, and I bought that schoolhouse for $200. Put a new roof on it, and rented it since I’ve been over here. I give it all to the young’uns, where Acie Lineberry’s store was. And that Highway from Asheboro to Liberty wasn’t built then. They built it with horses. That’s how long I’ve been there. I met my wife over here at Grays Chapel. She was a Hackett. She come from over at White’s Chapel. I got married the last week of the year. Went up there and still run around all over the country and everywhere else after I was married. Siler City and Seagrove, or below Seagrove, was as far as I ever went. You know what they call Black Ankle? I used to take to a store back in there, ten miles back on that river. Mandy’s Store. I’ve been in there and bought liquor since I been big enough to go back. See, I stayed down there, sold liquor, peddled liquor, and everything else. I don’t mind telling you. All around Franklinville, and Black Ankle, and everywhere else. I got pretty good on my feet then. In 1928, I had a little money I’d saved, and I got an A-model. Paid for it peddling liquor. But I went in debt building this bridge here in Central Falls in Twenty-eight. That’s where I went in debt. I made enough to get out there, but went in debt $500, and had to give my bootlegging car away.

But I had an old truck. Do you believe I drove an A model from Greensboro to Lancaster, Pennsylvania in one day? I had that truck, and I knew a boy that had business up there, and he helped me buy a new truck here, and I went to South Carolina and sold liquor; earned enough to pay for my land over yonder in two years. Now, then, what can you do in two years? Go in debt, that’s all you can do. But there was money in trucks, if you worked it out. I had to work it out; it wasn’t give to me. I went to Greensboro and I told them, I gonna mark me a route to Pennsylvania. He laid down a sheet of paper and said you just follow this highway till you hit the mountains. You don’t go round them mountains, go right on through them till you get to Pennsylvania. It’s seventy miles from where the President is over to Lancaster. I drove up there from 8:00 till 9 that night. I went by myself. My old truck was up there; kept my new one here, and went to South Carolina.

When I got out of debt I quit fooling with it. Old man Jewell Trogdon, a preacher here in town, he was the one caused me to get out. He just told me, over here in Gray’s Chapel Church, “What if the Lord would take these two girls away from you?” He knowed I was running around here and yonder and everything else. Old man Trogdon showed me where I was wrong. So I told the man over here who built this bridge, “Ed, you better make good of this liquor. These two cases is the last.” He said, “What do you mean? You can’t quit!” I said, “Yes, I have, I’ve done quit. You can drink it, but I ain’t even gonna sell this.” I stayed and got enough to pay for my land off what I done that year. I had $2,000 when I got done. I got my first truck in ’28, over here at Central Falls. And then went down there and got enough to pay for my land. And I went on to carpentry work, and never fooled with no more liquor.

I know time changes everything, but I’ve seen a lot of things since ‘seventeen.