1842: One hundred seventy three years ago; a lost world that is oddly similar to our own….

It is Monday, July 4th, 1842, and John Motley Morehead has been Governor of North Carolina for 18 months. A fellow cotton mill owner, Morehead is well known to those in Franklinville, and has probably already visited there. He lives in Blandwood Mansion in Greensboro and is related by marriage to General Alexander Gray of Trinity, the wealthiest man in Randolph County.

Morehead is a member of the Whig party, and the Whigs are firmly in control of the politics of Randolph County, and of North Carolina. Their hero is Henry Clay, congressman of Tennessee. Whig party members are progressive proponents of government taking an active role in economic development or, in the terminology of the times, “internal improvements.” They lobby for the creation of corporations to spin and weave cotton and wool, develop iron, copper and gold mines, and to build plank roads, canals and railroads. North Carolina, in fact, was in 1842 the home of one of the largest railroad networks in the world. The Wilmington and Weldon Railroad was built due north from Wilmington to Weldon on the Roanoke River near the state line. When completed in March 1840, it was at 161.5 miles long, the longest railroad in the world. A month later the Raleigh and Gaston line was completed running northeast from Raleigh, making Weldon a railroad hub. The Seaboard & Roanoke (east to Portsmouth, VA) and the Petersburg & Roanoke (north to Petersburg, VA) soon followed. It is now possible to buy a ticket in Raleigh and take the train, with numerous stops and changes, all the way to New York City.

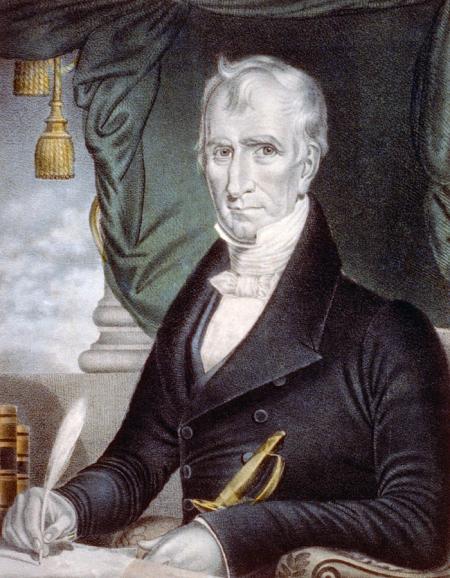

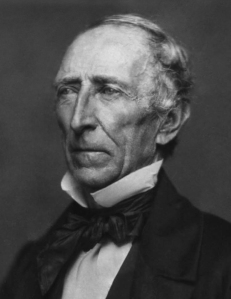

John Tyler is President of the United States, the 10th man to serve in that office. Tyler, a Virginian, is not held in high regard by the Whig party rank and file. Vice President just 15 months ago, he succeeded President William Henry Harrison in April 1841. General Harrison, a hero of the Indian Wars and the oldest man ever elected President, caught pneumonia during his inauguration and died barely a month later. He was the first President to die in office. In the contentious “log cabin and hard cider” campaign of 1840 General Harrison beat the highly unpopular incumbent Martin van Buren. Van Buren had been Andrew Jackson’s hand-picked successor, but he had the bad luck to take office in March 1837 just as the “Panic of 1837” sabotaged the economy. Private speculators who bought land trying to capitalize on the railroad boom lost everything when the bubble burst; businesses failed and unemployment was widespread. Even worse, state governments had borrowed heavily from foreign banks to finance construction of new canals, turnpikes and railroads, and without those tolls and fees they found themselves unable to pay their overseas creditors.

In the summer and fall of 1841, Michigan, Indiana, Arkansas, Illinois and Maryland all defaulted on their payments to London banks. Florida and Mississippi defaulted in March 1842, and Pennsylvania and Louisiana would soon follow suit. In June treasury agents in London were unable to sell U.S. bonds despite the fact that the federal government had completely paid off its national debt six years earlier. Parisian banker James (Jakob) Rothschild sent word, “You may tell your government that you have seen the man who is at the head of the finances of Europe, and that he has told you that you cannot borrow a dollar, not a dollar.”

Anger over the defaults renewed America’s negative attitudes toward Britain, the country’s original enemy. State politicians were outraged at the thought of imposing additional taxes on citizens already in the depths of a financial depression, just to honor commitments to European bankers. The governor of Mississippi proposed to repudiate the debt to “the Baron Rothschild… the blood of Shylock and Judas flows in his veins. It is for this people to say whether he shall have a mortgage on our cotton fields and make serfs of our children.” [Note: Mississippi still has never paid that debt.] An Illinois legislator named Abraham Lincoln called for Federal assistance to the western states, “in the midst of our almost insupportable difficulties, in the days of our severest necessity.”

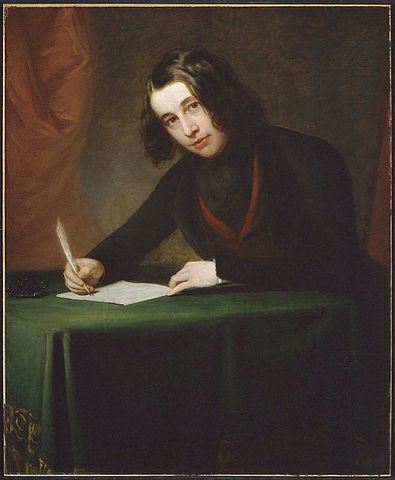

President Tyler refused to intervene. After all, it was those Democrats Andrew Jackson and his minion Van Buren who had promoted all this speculation and unwise public investment. Congress twice attempted to ease credit by voting to re-establish a central bank for the country, and twice Tyler vetoed the bills, leading to the resignation of almost all of his cabinet in September 1841. Tyler was burned in effigy outside the White House. Charles Dickens, who arrived in Washington in March 1842 on his first tour of the United States, wrote that the President looked “worn and anxious, and well he might, being at war with everybody.”

And apparently financial conditions were going to get worse. A decade earlier Congress had promised to reduce federal tariffs on foreign imports and exports. Those tariffs had been designed to protect the infant industries of the Northern states, but rankled the agricultural South who wanted free access to the huge British demand for cotton. The date for reduction had been fixed by the law: June 30, 1842. But with incomes reduced by five years of depression, tariffs now account for 85 per cent of federal revenue, and any reduction in the tariffs would require big cuts to the federal budget. Just before the deadline, Congress passes a bill to temporarily preserve the tariffs, and provide aid to the West. But Tyler, sympathetic to southern cotton interests, vetoes it. A London newspaper reports, “The condition of the country is most appalling. The treasury is bankrupt to all intents and purposes.” [All quotes come from the best work on this subject, “America’s First Great Depression: Economic Crisis and Political Disorder After the Panic of 1837,” by Alisdair Roberts (Cornell Univ. Press, 2012).]

So why, in the midst of this depression and governmental breakdown and international credit crisis, was the tiny new town of Franklinsville hosting what might be the biggest celebration in its history?

The simplest explanation is to look at Franklinsville as a little outpost of New England in the countryside of North Carolina. The tariffs had been designed to promote and protect the industrial revolution in the United States, and it just so happened that its birthplace was in New England. The tariff that protected a cotton mill in Massachusetts also protected the cotton mills in North Carolina- what few there were. Randolph County Whigs, in particular, had little love for the plantation cotton economy, and its exploitation of enslaved African labor. The local economy was built on production of wheat and corn, and these were not export items. As early as 1828 Randolph County Whigs had proposed building a cotton mill, but not until 1836, after the tariff was in place, did investors build the first small factory at Cedar Falls.

That first mill had started with cotton spinning equipment inserted into the grist mill of Benjamin Elliott, a former Clerk of Superior Court. With the financial support of Dr. Philip Horney and his son Alexander, and under the management of his son Henry Branson Elliott, the tiny new factory at Cedar Falls made “bundle yarn” which was sold at the Elliott store on the courthouse square in Asheboro.

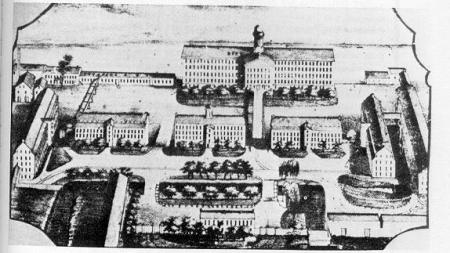

The “Randolph Manufacturing Company,” organized in March, 1838, built on the successful experiment at Cedar Falls. Located at “Coffin’s Mills,” the site of Elisha Coffin’s wheat, corn, and saw mills and cotton gin about 2 miles downriver from Cedar Falls, the new factory was built on a New England plan. For example, after being chartered by the legislature, it was operated not as a loose partnership but as a corporate body of stockholders- the first corporation ever to conduct business in Randolph County. Second, it was designed using a completely new scale. The three story, 40 by 80-foot “Factory House” was the first building built in the county textile manufacturing purposes, and was probably one of the first ten in the state. It was also one of the first brick structures in the county, and was certainly the largest building in Randolph County when completed. Finally, the cotton mill would have the first looms in the county, weaving cloth where Cedar Falls could only spin. The Franklinsville factory thus was the first “integrated” manufacturing operation (the first to manufacture cotton in all stages “from bale to bolt” of woven cloth.)

That it still made good financial sense to build the Franklinsville factory even after the Panic of 1837 took hold shows that the Randolph County economy was different from the rest of the South. None of this investment would have been possible without the protection of the tariff; otherwise the American market would have been flooded with British cloth and yarn, made and imported more cheaply than the small local factories could compete with. The Asheboro newspaper reported that “Since the commencement of their works but one short year ago, a little village has sprung up at the place which has assumed the name of Franklinsville, embracing some eight or ten respectable families. A retail store of goods has just been opened here on private capital. And the company have now resolved to establish another one on part of their corporate funds.” [Southern Citizen, 8 March 1839.]

In 1840 Benjamin Swaim, the editor of the Asheboro newspaper Southern Citizen, reported that he “had occasion to visit Franklinsville last Monday, which gave us an opportunity of viewing the Work. It appears to be going finely. The Factory House, (a very large brick building) is nearly completed; and they are putting up the Machinery. It is expected they will commence spinning in a few weeks – by the first of March at furtherest. Success attend their laudible enterprize.” [Southern Citizen, 21 Jan. 1840.]

A letter from a Randolph resident to his son in Texas (LF William Allred to son Elijah Allred), written in July 14, 1843 but perfectly capturing the lingering spirit of the times of a year earlier, wrote that “produce is plenty and market low Owing I believe to the Bad economy of Our Government Rulers for ever since the contest has raged so high about Moneyed Institutions that people is afraid to engage money on account of the Scarcity of that article; Before that Embarasment, I thought this Old Country was Improving verry fast; the two Cotten factories one at the Cedar Falls and the other at Coffin’s Mill, now called Franklinville, they Manufacture vast quantities of Cotton thread and Cloth and sells thred at ninety cents for five pounds and cloth from eight to ten cents per yard.”

So, while times seemed dark for much of the country, times in the new town of Franklinsville were looking sunny, and the owners and stockholders had arranged to celebrate the success of their risky investment. It is a short news article, but it has much to say about the times, and perhaps about our own.