I realized today that there is a major Franklinville anniversary coming up this month. One hundred twenty years ago, on Thanksgiving Day, November 25, 1897, the “Upper Mill” started up its second steam engine- an engine that still exists, though no longer in Franklinville, and still has lessons for us about powering manufacturing.

The interior of P&P Chair Company in Asheboro, where the lineshaft down the center of the building was originally powered by a Corliss engine.

Before the advent of individual electric motors to power machinery, finding the energy to manufacture goods involved harnessing natural resources to mechanical processes. The most important requirement was a plentiful source of water, required by steam engines and boilers as well as by water wheels. Whether turned by the force of flowing water or high-pressure steam, a rotating flywheel pulled a leather belt, transmitted through a complicated system of shafts, belts, ropes and pulleys to connect each individual machine to the rotating wheel.

Breast wheel in ruins of Richmond Va. paper mill, 1865

The mill’s original power came from one or more wooden water wheels of the breast (or “pitch-back”) type, the usual form of water wheel usually found in British and New England textile mills. . The entire reason to locate the factory at this spot on Deep River was to take advantage of the potential for water power, so a water wheel had to have been part of the original construction of the mill. The earliest written reference to any Deep River factory wheel comes in 1848, when a reporter mentions the two metal breast wheels installed in the rebuilt Cedar Falls factory, built by the Snow Camp Foundry.

The original water wheels installed in the 1849 Union Factory in Randleman were Howd’s “cast iron direct-acting water-wheel…,which works under back water while there is sufficient head above.” Samuel B. Howd patented an inward-flow reaction wheel in 1838, which used only two-thirds of the water needed by breast wheels, and ran in times of “back water,” meaning a flooded tail race. [The Patriot, 18 August 1849]. But no wheel could run regularly without a constant flow of water, and for that reason the Union factory installed the first steam engine on the river, apparently in 1878 [Charlotte Observer, 12 November 1879].

The breast wheel in Franklinville was probably covered at least with a shed to protect it from ice, but it is not clear what, if any, structure covered the wheel until July, 1882, when the capital stock of the corporation was increased by $20,000 to allow construction of a two-story “Wheel House.” A new water wheel was evidently installed even before the Wheel House was complete, as “The Franklinsville Manufacturing Company have just started up a lot of new machinery,” said the Chatham Record in February 1881; which included an American turbine water wheel, made by the Dayton Globe Iron Works in Ohio [says the Wilmington Post of 24 July 1881].

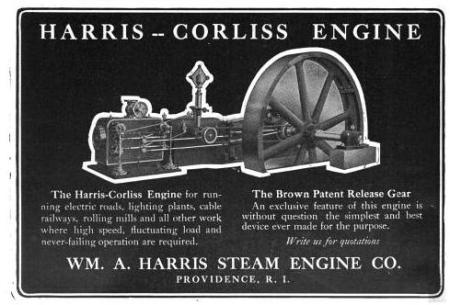

But water power is another story; this post is about steam, and the first steam boiler started to power the Franklinville factory about that same time. The records of the William A. Harris Steam Engine Company of Providence, Rhode Island (now in the New England Museum of Wireless and Steam) indicates that an 87-horsepower right-hand drive girder frame Corliss-type engine with a flywheel eleven feet in diameter was ordered by the Franklinsville Manufacturing Company on March 29, 1882.

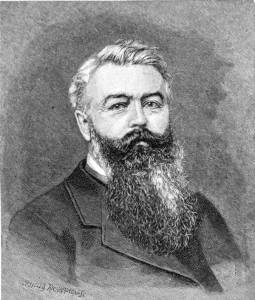

George Corliss

The reciprocating steam valve patented by George Corliss in 1849 allowed for uniform speed and more efficient cutoff of steam, and quickly became the preferred industry standard for large mill engines. William Harris, formerly a superintendent in the Corliss factory, opened his own firm in 1864. Between 1874 and 1899 he delivered 18 engines to North Carolina manufacturers, including one to Randleman in 1881, one to the fomer Island Ford factory in Franklinville in 1896, and one to Cedar Falls in 1898.

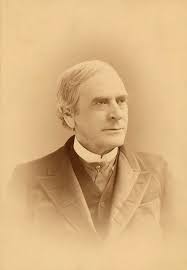

William A. Harris

Corliss engines were the workhorses of manufacturing in America. Franklinville alone, circa 1890, had four– at both cotton mills, the Bush Creek rock crusher, and the Makepeace Millworks. All of the big smokestack industries in Asheboro were powered by corliss engines; yet by 1950, all had been replaced by cheap electricity powering motorized equipment. The Age of steam-powered prime movers, 1880-1940, was barely one man’s lifetime.

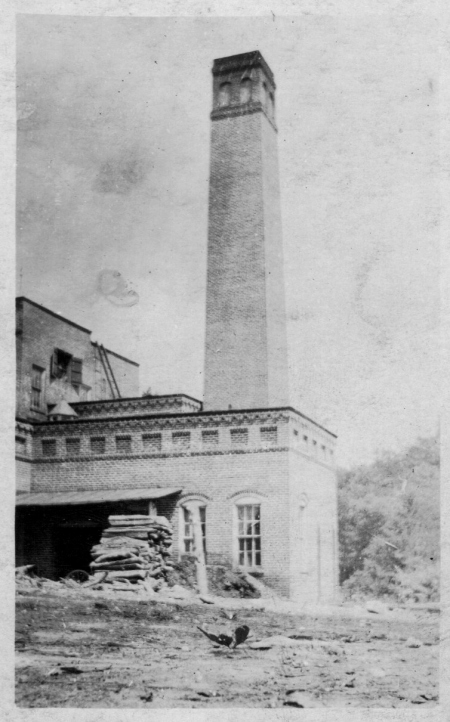

Franklinsville Mfg. Co. 1897 boiler room and smokestack

The 1882 Franklinville engine was located in the Wheel House, and a Boiler Room was added to the south of the wheel house, together with a 69-foot-tall brick chimney flue for the boiler, fired by wood. The steam engine operated for the first time on November 24, 1882. An electric dynamo was attached to the water wheel in the fall of 1896, and in October the first electric lights were installed in the mill. (The superintendent noted that “then tallow candles and kerosene lamps became a thing of the past.”)

1897 FMC Harris Corliss Engine, front view, 1995

In 1895 the mill began an expansion plan which resulted in doubling the size of the factory by 1899. To prepare for that, in 1897 the boiler room was expanded, a taller smokestack was erected, and a new engine house was built to house a bigger 150-horsepower Harris Corliss engine. Evidently satisfied with the performance of its 1882 engine, the mill went back to the William A. Harris Company and ordered a new engine even larger than the old one.

1897 engine, rear view

Ordered on July 29, 1897, the engine boasted an 18” cylinder and a 42” stroke, and provided more than 100 horsepower to the flat-belt pulley on its 13-foot flywheel. A new engine house was built, with granite bed stones anchored in a wheel pit deep beneath the mill. The engine was started for the first time on Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 25, 1897, “by Benajah T. Lockwood of Providence, Rhode Island.” The engine turned continuously until December 23, 1920, when the new coal-fired Power House was built, and electric motor drives were installed in the mill.

What kind of boilers generated steam for the earliest engines isn’t yet known, but by1907 the Upper Mill needed the output of three boilers: two second-hand Keeler boilers from the Lower Mill [E. Keeler & Co. of Williamsport, PA], and a new 230-horsepower Atlas Engine Works water tube boiler made in Indianapolis. [Greensboro Daily News, 8 May 1907].

1897 FMC engine, showing steam chest with corliss valve gear, Nov. 2017

In 1921 the Franklinville engine began a remarkable journey around North Carolina- remarkable for a machine the size of a box truck and weighing many tons. In July, 1921 it was sold to Builder’s Sash and Door Company of Rocky Mount, where it operated until April of 1933. It was then purchased by the Williams Lumber Company and moved to their mill in Wilson. Williams Lumber became Stevens Millwork in 1965, and the engine continued to run their saw mill and millwork shop until 1971, when the company closed. Scrap dealers disassembled the engine and sold it to someone who moved it to Smithfield, NC, but never set it up. There it was discovered by Shell Williams of Godwin, NC, who used a crane and lowboy to move it to Cumberland County in 1977, where it remains.

1897 FMC engine, showing governor

November 25, 2017 will be the 120th anniversary of this workhorse machine first coming to life in Franklinville, NC. It powered at least 3 different North Carolina manufacturers for more than 75 years, and could still go on for years more. It is a monument to American mechanical design and craftsmanship, as well as to the manufacturing power that built our modern economy. A good reason to pause and remember the hard work of all the people who designed it, built it, moved it, operated it, and cared for it for more than five generations in Rhode Island and North Carolina.

Robert Merriam, of the New England Museum of Wireless and Steam, operating their 1892 Harris Corliss engine.