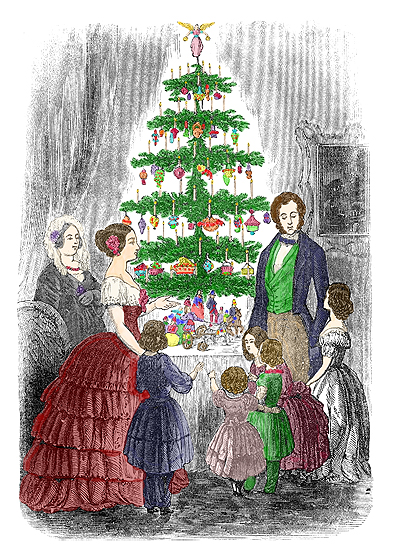

Godey’s Lady’s Book, 1850- a revised version of the Illustrated London News, edited to Americanize Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

North Carolina in 2014 ranks number two in the nation in Christmas tree production, right after Oregon. Every year the state’s 1600-odd tree farms produce some 50 million Fraser Firs, the most popular type of Christmas tree, worth about $100 million dollars.[i] Add that to the relentless drumbeat of Christmas music and lights and shopping, it is hard to realize that Christmas wasn’t always the way it is today.

If you flip back to my 2010 post of Nannie Steed Winningham’s reminiscence of the Confederate Christmases of 1862, ’63 and ’64,[ii] you will note that there is no mention whatsoever of Christmas trees. Santa Claus came down the chimney, as usual, and filled up the family’s stockings with gifts. There was too much eggnog, and there was a visit by the scary “Christmas Waifs” demanding hand-outs. But no tree.

In fact, Christmas was not at the time of the Civil War an actual official holiday. As Dickens had Scrooge point out in A Christmas Carol, it was up to an individual’s employer whether to give the day off from work. The City of Asheboro itself was created on December 25, 1796, when the state legislature, meeting for a regular work day, passed “An Act to Establish a Town on Lands of Jesse Henley, in the County of Randolph, at the Court House of said County.” Not until 1870 did Congress establish Christmas as a federal holiday.

The modern American versions of both Thanksgiving and Christmas began to take shape during the Civil War period, and both traditions owe much to the editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, who lobbied regularly for Americanized holidays. The magazine at Christmas, 1850, printed the first widely-circulated picture in America of a decorated Christmas evergreen; it was a repurposed 1848 engraving of the British Royal Family with their tree at Windsor Castle which had been published in The iIllustrated London News.[iii] Reprinted throughout the 1860s, the image became the iconic picture of an American Christmas tree.

Another influential magazine, Harper’s Weekly, is largely responsible for our modern image of Santa Claus himself. Cartoonist Thomas Nast, a sketch artist for the magazine, created an illustration for the Christmas, 1861 issue to accompany the Clement Clarke Moore poem, “’Twas the Night Before Christmas.” That was the first published image of Santa in a reindeer-drawn sleigh with a bag full of gifts slung over his shoulder.

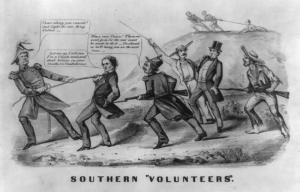

However, the fact that Nast also showed Santa delivering copies of Harper’s as gifts to Union soldiers on the war front soured the picture for Southerners. The Richmond Examiner editorialized that this Northern image of Santa Claus was nothing more than an “Dutch toy-monger,” a “transflated scrub” from New York and New England “who has no more to do with genuine Virginia Hospitality and Christmas merry makings than a Hottentot.”[iv]

It wasn’t that Christmas trees were unknown in America at that time. The British Royal Family brought the custom into England, and in a backhanded way North Carolina has a tie to that. The wife of George III, Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (the namesake of Charlotte and Mecklenburg county), set up a Christmas tree at a party she gave for children in 1800. Princess Victoria liked the custom and a tree was placed in her room. In her journal for Christmas Eve 1832, the 13-year-old princess wrote:

“After dinner… we then went into the drawing-room near the dining-room… There were two large round tables on which were placed two trees hung with lights and sugar ornaments. All the presents being placed round the trees…”[v]

The custom became even more widespread after Victoria’s marriage to her German cousin Prince Albert, and by the early 1840s there were newspaper ads for Christmas trees that promoted their fashionable German origins and their popularity with children. The Moravians of Salem are thought to have brought the custom of Christmas trees to North Carolina. Randolph County had its few Moravians, but even more Lutherans, Amish, Dunkers and other German sectarians. But I have seen no record of their Christmas celebrations.

The first reference to a Randolph County Christmas tree that I know about comes from the manuscript “Reminiscences” of W. M. Curtis, a carbon typescript dated 1940. Walter Makepeace Curtis (1867-1955), a Methodist minister, was Secretary-Treasurer of Greensboro College for 34 years. His autobiography begins,

“I was born on February 18, 1867, in Franklinsville, Randolph County, North Carolina. My home was on an island with Deep river on the south and a mill race on the north. This race began at a dam across the river at the west end of the village and emptied into the river at the Franklinsville cotton mill.

… My father, Dennis Cortes Curtis [1826-1885] (he always signed his name D. Curtis) was the son of James Curtis, a farmer who lived a few miles south of Franklinsville….

“There was a public schoolhouse for the children of the village near the Methodist Church, but the school was in session only three months of the year, and my father was anxious for his children to have better educational opportunities so he employed a governess… My father was superintendent of the Sunday School in the Methodist Church, and he took me to Sunday School when I was quite small….

“At Christmas we had a Christmas tree in the Sunday School. The tree was always a large holly with red berries. Some time before Christmas my father would drive to Greensboro and purchase presents and decorations for the tree. On the night before Christmas, as soon as it was dark, my little four-wheel wagon was loaded with Christmas things and I, with some help, pulled the wagon up to the church, where my father and others arranged the decorations and presents on the tree. Individuals were permitted to have their presents, with the name of the recipient on each one, hung on the tree. There were a good many of these, and it was interesting to hear the names called out. Each one receiving a present would go forward and get the gift. This Christmas tree celebration was always held on Christmas Eve, and was quite an event in the village.”

Although Curtis doesn’t give a specific date for this tree, it had to date from before the Curtises moved to Greensboro in 1880, and probably can be attributed to the period around 1875.[vi]

The first published American illustration of a Christmas Tree, from The Stranger’s Gift, printed in Boston, 1836.

This is in accord with the introduction of trees into Christmas celebrations; they often were introduced to the public places at churches, hospitals and charity bazaars, and their familiarity there slowly led people to set up private trees at home. It also seems to have been understood that Christmas trees were used to provide gifts for the underprivileged. Varina Davis noted in her 1896 recollection of Christmases in Richmond during the war years, ” like a clap of thunder out of a clear sky came the information that the orphans at the Episcopalian home had been promised a Christmas tree and the toys, candy and cakes must be provided…” [http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/on-the-homefront/culture/christmas.html] As late as 1906 a charity was set up specifically to introduce decorated trees to poor children in London slums ‘who had never seen a Christmas tree’.[vii]

The first Yule trees were small ones that sat on a table, decorated with dried fruit, popcorn, pine cones and homemade paper chains and baskets for nuts. A tree was not brought into the house and decorated before December 23rd, “the traditional “First Day of Christmas,” and the beginning of the 12-day Christmas season that ended on Twelfth Night (January 5th). To have a tree up before or after those dates was considered bad luck.

Not all Christmas trees were evergreens. In the late 1800s and, most probably, long before, home-made white Christmas trees were made by wrapping strips of cotton batting around leafless branches creating the appearance of a snow-laden tree. Only those presents too large to be hung on the tree were placed on the tree skirt underneath the tree. Most presents were small, and edible gifts were among the most highly prized gifts hung in small baskets on the tree. During the war, one soldier from a New Jersey regiment recorded in his diary, “In order to make it look much like Christmas as possible, a small tree was stuck up in front of our tent, decked off with hard tack [a hard cracker] and pork, in lieu of cakes and oranges, etc.” [viii]

(Even in the early 1960s, those of us who watched “The Old Rebel and Pecos Pete” on WFMY Channel 2 knew that the only proper ending of our answer to the question “What do you want for Christmas?” was “X,Y,Z, -and Nuts and Fruits and Candies.” As late as 1943, the singer of the wartime song “Ill Be Home for Christmas” was longing for “presents on the tree” (not under the tree).

This was a survival of the ancient European tradition. Decorated trees were part of the stage sets for medieval religious mystery plays that were given on December 24th on the “name days” of Adam and Eve. Those trees were hung with apples (the “forbidden fruit”) and wafers (representing the Eucharist and redemption). Bakers made pretzels and gingerbread cookies for the tree that people took home as souvenirs. In 1570 a small tree set up in the Guild-House in Breman, Germany was decorated with “apples, nuts, dates, pretzels and paper flowers”. In 1605 a German visitor wrote: “At Christmas they set up fir trees in the parlours of Strasbourg and hang thereon roses cut out of many-coloured paper, apples, wafers, gold foil, sweets, etc.” The many food items were symbols of Plenty, the flowers, originally only red (for Knowledge) and White (for Innocence).

Americans did not take easily to the foreign custom of Christmas trees. Franklin Pierce had the first Christmas tree in the White House in 1846. But President President William McKinley reportedly received a letter in 1899 saying Christmas trees “un-American,” and his successor Theodore Roosevelt banned Christmas trees from the White House because he feared that Christmas trees would lead to deforestation. Roosevelt, however, was undercut by his own youngest sons, Archie and Quentin, who in 1902 went outside and cut down a small tree right on the White House grounds and hid it in a White House closet. Roosevelt acknowledged the event in a letter in which he wrote:

Yesterday Archie got among his presents a small rifle from me and a pair of riding boots from his mother. He won’t be able to use the rifle until next summer, but he has gone off very happy in the riding boots for a ride on the calico pony Algonquin, the one you rode the other day. Yesterday morning at a quarter of seven all the children were up and dressed and began to hammer at the door of their mother’s and my room, in which their six stockings, all bulging out with queer angles and rotundities, were hanging from the fireplace. So their mother and I got up, shut the window, lit the fire (taking down the stockings of course), put on our wrappers and prepared to admit the children. But first there was a surprise for me, also for their good mother, for Archie had a little birthday tree of his own which he had rigged up with the help of one of the carpenters in a big closet; and we all had to look at the tree and each of us got a present off of it. There was also one present each for Jack the dog, Tom Quartz the kitten, and Algonquin the pony, whom Archie would no more think of neglecting that I would neglect his brothers and sisters. Then all the children came into our bed and there they opened their stockings.[ix]

It sounds to me as though Teddy’s idea of Christmas was not very different from Nannie Winninghams- stockings were the place Santa left the presents. More than 100 years later, what we think is our “traditional” Christmas has been shaped by the media, retailers, film and recorded music of the 20th century more than we ever realize.

[i] WUNC TV website data.

[ii] https://randolphhistory.wordpress.com/2010/12/10/confederate-christmas-in-randolph-county-2/

[iii] Karal Ann Marling (2000). Merry Christmas! Celebrating America’s greatest holiday. Harvard University Press. p. 244.

[iv] Marten, James (2000). The Children’s Civil War. University of North Carolina Press. P120

[v] The Girlhood of Queen Victoria: A Selection from Her Majesty’s Diaries, p.61. Longmans, Green & Co., 1912

[vi] The obituary of Curtis’s mother in the Greensboro Daily News of 23 August 1918 gives frame for this assumption-

“Mrs. Lucy Ellen Makepeace Curtis died at her home, 108 Odell Place, yesterday afternoon, at 4:15 o’clock. For a number of years, Mrs. Curtis had been living with her son, Rev. W.M. Curtis, of this city. Mrs. Curtis was born at Petersburg, VA, December 25, 1839. Soon after her birth her parents, George Makepeace and Mrs. Luc Makepeace, settled at Franklinville, where she grew up. She was married to Dennis Curtis, of Franklinville, October 11, 1860. Dennis was a native of Randolph County and was prominently connected with the Franklinville Manufacturing Company, the Deep River Manufacturing Company, and later with the mercantile business firm of Odell and company of this city. In 1880 Mrs. Curtis moved from Franklinville to Greensboro when Mr. Curtis became personally associated with the firm of Odell and company….”

[vii] http://westminsterabbeyshop.wordpress.com/2014/12/12/the-history-of-the-christmas-tree-in-britain/

[viii] http://www.historynet.com/christmas-in-the-civil-war-december-1998-civil-war-times-feature.htm

[ix] http://www.ncregister.com/blog/matthew-archbold/the-president-who-banned-christmas-trees-and-the-boy-who-snuck-one-in#ixzz3MVw7I6Qj