Published in the Raleigh Register, Friday, 15 July 1842–

Published in the Raleigh Register, Friday, 15 July 1842–

The Raleigh Register and North-Carolina Weekly Advertiser was published weekly in Raleigh beginning in 1799, and in various formats and title variations to 1852. Its publisher, Joseph Gales, was a well-known British immigrant who was sympathetic to the French Revolution and Thomas Jefferson. It was a leading poltical voice in North Carolina, first for Jefferson’s Republican Party and later for the Whig Party. Gales became one of Raleigh’s leading citizens and advocated for internal improvements and public education. He privately favored the emancipation of slaves and publicly advocated for the American Colonization Society. He served several terms as Mayor of Raleigh, and was doing so when he died, 24 Aug. 1841. His son Weston Gales was editor and publisher of the newspaper in July 1842.

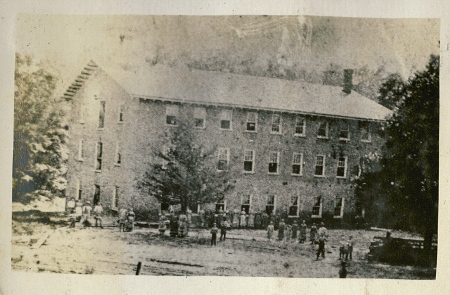

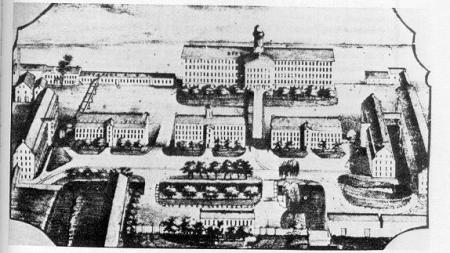

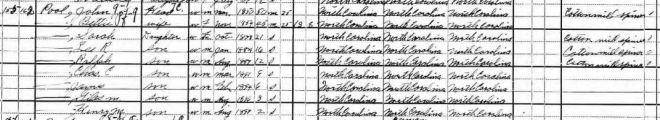

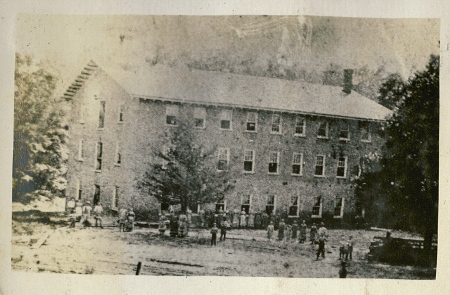

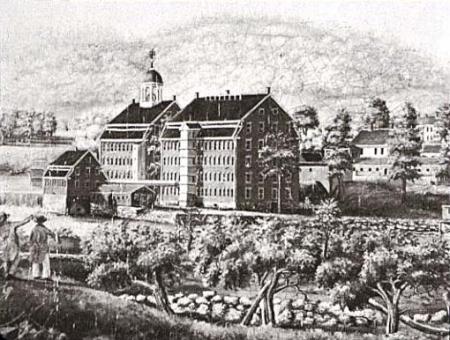

Upper Mill before 1946 (no laboratory, b. 1946)

“Celebration at Franklinsville, Randolph County”–

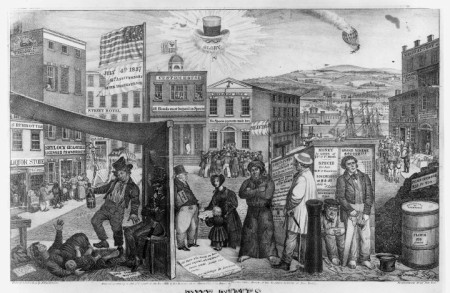

The writers had to be specific, as most readers in Raleigh and the rest of the state would not have been familiar with the tiny community, less than 4 years old. Modern Franklinville is made up of two initially independent mill villages, Franklinsville and Island Ford, separated by about three-quarters of a mile of Deep River. The original Franklinsville mill village was developed by the mill corporation beginning in 1838, on property adjoining the grist mill on Deep River belonging to Elisha Coffin. Coffin, a miller and Justice of the Peace, purchased the property in 1821. [Deed Book 14, p.531 (Ward to Elisha Coffin, 25 Dec. 1821)] Coffin was the initial incorporator of the factory, and developed the new town on the slope between his house and the mills. The community formerly known as “Coffin’s Mills on Deep River” had “assumed the name of Franklinsville” by March 8, 1839. Officially named to honor Jesse Frankin, a former N.C. Governor and Congressman from Surry County, unoffically Coffin and his anti-slavery family and investors apparently meant to honor Franklin for his crucial vote to keep slavery out of the Northwest Territory (now Ohio, Indiana and Illinois). “Franklinsville” was officially recorded in the town’s 1847 legislative act of incorporation.[ Chapter 200, Private Laws of 1846-47, ratified 18 Jan. 1847]. The community surrounding the factory was the largest urban area in Randolph County until 1875.

“The Visitors… amounted to 1200 or 1500”-

The entire population of modern Franklinville is less than 1500; the 1840 census of Randolph county found the total population to be 12,875 people, so if 1500 people actually attended this event, that would have constituted about 11% of the residents of the entire county in 1842.

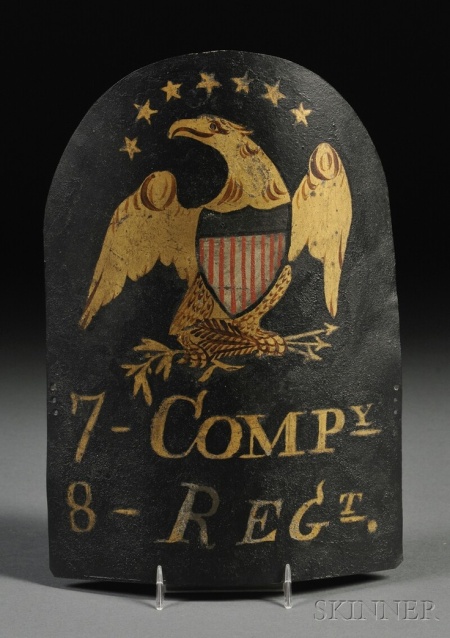

OSV Marines 1812

“The Franklinsville Volunteer Company of Light Infantry”-

The state militia, organized by county and divided into “Captain’s Districts,” had been the foundational political body in North Carolina since colonial times. The militia had been reorganized in 1806 (Revised Statutes, Chapter 73) to allow “Volunteer”companies raised by private subscription in addition to the official “Enrolled” companies made up of “all free white men and white apprentices, citizens of this State, or of the United States residing in this State, who are or shall be of the age of eighteen and under the age of forty-five years…” Enrolled companies were known by the name of the commanding Captain, and Randolph County was divided geographically into about 12 Captain’s Districts, which functioned much like modern voting precincts. Each district had its own “muster ground,” and four times each year were required to assemble and practice military drills. One of the annual musters was usually also election day, and the men voted by district.

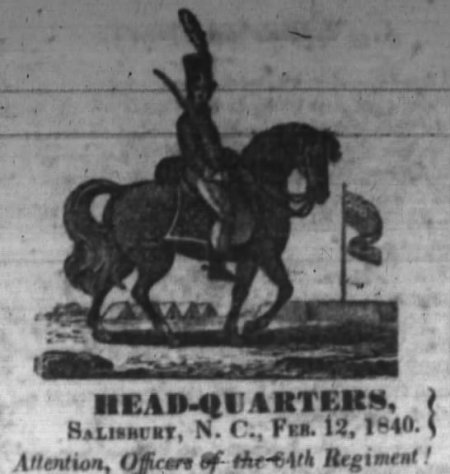

NC Militia Officer 1840

Prior to the creation of the new town of Franklinsville, men of that area of Deep River were considered to be part of the “Raccoon Pond District,” unusual in the fact that it was named after a geographical feature and not after its Captain. As Captains often changed, making the location of muster fields and districts hard to pin down, this distinction allows to us pinpoint the area of the Raccoon Pond District, even though the pond has over the years silted up and is no longer known as a modern landscape feature. Raccoon Pond (by the account of Robert Craven and other local residents) was situated at the base of Spoon’s Mountain, south of the modern state road SR 2607 and west of its intersection with SR 2611, Iron Mountain Road. The Spoon Gold Mine was located in the area later in the century, and probably helped to silt up the pond. The enrolled militia of the Raccoon Pond District in 1842 was evidently headed by Captain Charles Cox.

Volunteer militia companies were considered the elite of the citizen army and their members were exempt from service in the enrolled companies. Because they were organized and equipped by those who could afford to raise their own private company, volunteer companies enjoyed preferential placement in reviews, and were often the last to see actual service. Volunteer companies also functioned as social organizations, sponsoring dances and suppers to entertain ladies; could dress themselves in elaborate uniforms, and were usually known with impressively martial names such as “Dragoons,” “Light Infantry,” or “Grenadier Guards.” The “Fayetteville Independent Light Infantry,” formed in 1793, is a unique survivor of this type, and is known as “North Carolina’s Official Historic Military Command” They provide an honor guard at special events, funerals and dedications.

http://www.fili1793.com/ The Washington Light Infantry (WLI), organized in Charleston in 1807, is another of these old original militia units, named in honor of George Washington.

Independence Day OSV 2

Technically, light infantry (or skirmishers) were soldiers whose job was to provide a protective screen ahead of the main body of infantry, harassing and delaying the enemy advance. Heavy infantry were dedicated primarily to fighting in tight formations that were the core of large battles. Light infantry sometimes carried lighter muskets than ordinary infantrymen while others carried rifles. Light infantry ironically carried heavier individual packs than other forces, as mobility demanded that they carry everything they needed to survive. Light infantrymen usually carried rifles instead of muskets, and officers wore light curved sabres instead of the heavy, straight swords of regular infantry.

The name “Franklinsville Volunteer Company of Light Infantry” was evidently a cumbersome mouthful, as it was officially reorganized in 1844 as the “Franklinsville Guards.” See the Session Laws of the General Assembly of 1844/45: The legislature went into session on 18 Nov. 1844, and Henry B. Elliott of Cedar Falls was accredited to represent Randolph County (Senate District 35). (Thurs. 11-28-44) “Mr. Elliott presented a Bill, entitled A Bill to incorporate the Franklinsville Guards in the County of Randolph, which was read the first time and passed.” (p57). The Bill was passed a second time by the Senate on Monday 2 Dec. 1844 (p78); and passed and third time, engrossed and ordered to be sent to the House on Tuesday 3 Dec. (p84). The House of Commons received the engrossed bill and a note “asking for the concurrence of this House” on 23 Dec.; it was read the first time and passed that day (p277), and was passed the final time on Jan. 1, 1845 at 6:30 PM. (p652).

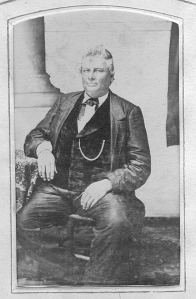

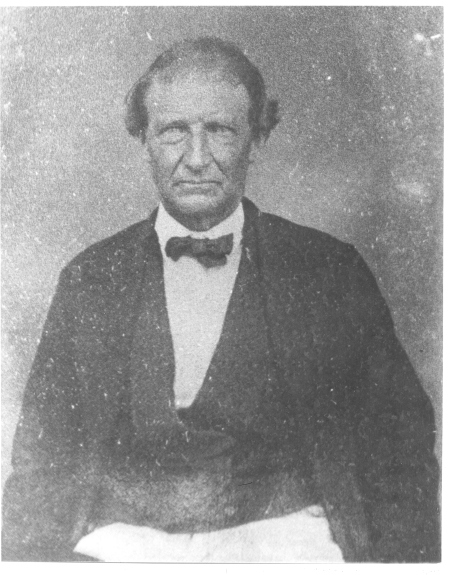

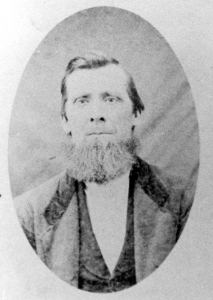

Alexander S. Horney, circa 1870.

“Captain Alexander Horney”-

Alexander S. Horney (26 March 1815 – 19 July 1891), was the son of Dr. Philip Horney (1791-1856). Both sides of his family, the Horneys and the Manloves, were well-known Guilford County Quaker families. Like Elisha Coffin, Dr. Horney may have been forced out of communion with Friends by his marriage to Martha (“Patsy”) Smith (?-1871). The small wooden factory which opened at Cedar Falls in 1836, was owned in partnership between the Horneys and Benjamin and Henry Elliot, father and son lawyers. Alexander S. Horney married the daughter of Elisha Coffin; their son Elisha Clarkson Horney was mortally wounded at Gettysburg. Their daughter Mattie married Robert Harper Gray, the son of General Alexander Gray. Robert Gray was the captain of the Uwharrie Rifles, a volunteer company raised in 1861 in the Trinity area. He died in service in 1863. Alexander S. Horney served as chairman of the county commissioners for many years after the war.

Muster Ground?

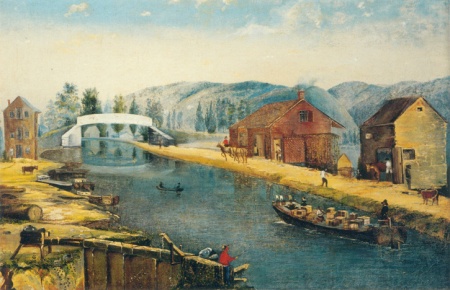

“the area skirting the North side of the Factory”-

This must refer to the company muster ground, but I think that the writers must have meant the area to the East side of the factory, which was (and is) a level area of bottom land. The area to the north would not have provided more than 50 feet of manuvering space. Franklinville is sited on a penninsula bordered on the South by Deep River, on the east by Sandy Creek, and on the West by Bush Creek. The land rises toward the northwest from the floodplain of the river, where the mills were located which provided the economic backbone of the village, together with their ancillary warehouses, storehouses, and barns. On a level about ten feet above the mill to the north were located the company store and company boarding house; to the south and across the mill race were the homes of the miller and company president. North of the store on a terrace about fifteen feet higher was the “Cotton Row,” housing built by the mill for the workers. About ten feet higher still, and trending northwest up the hillside, were located the larger homes of tradesmen, craftspeople and professional men such as Dr. Phillip Horney. The lots higher up the hill had been sold privately to friends and family members by Elisha Coffin, promoter of the factory and owner of all the acreage around the mill. Lots for public institutions such as the school, meeting house, cemetery and town hall were located near the top of the river-front arm of the hill, with stores fronting the road leading north toward Greensboro. At the crest of the hill was situated Elisha Coffin’s own house, surrounded by its community of “dependencies”—office, kitchen, smokehouse, well house, icehouse, dairy, animal sheds, stable, barn, and servant houses.

George Makepeace circa 1850

“the Grove fronting the residence of Mr. Makepeace”-

George Makepeace (1799-1872) was a textile manufacturer and millwright born in Norton, Massachusetts. He and his brother Lorenzo Bishop Makepeace had been owners and operators of a cotton mill in Wrentham, Massachusetts, which failed in the mid-1830s. Lorenzo Makepeace was hired to work in a factory in Petersburg, Virginia, and Elisha Coffin may have heard from him about the availability of George Makepeace during his trip “to the North” on company business in 1838. Makepeace and his family were on their way to Randolph County when his daughter Ellen was born in Petersburg, Virginia, on Christmas Day, 1839. As a skilled expert in textile technology, Makepeace was much in demand around the Piedmont.

The location of Makepeace’s residence in 1842 is unclear, as he rented from the factory corporation. Given the description of the Coffin house as being “on the opposite hill” from the Makepeace house, I am assuming that one of the homes on the east side of Walnut Creek is indicated. It could have been one of the three mill houses on the hill south of the modern Quick Check, or it could have been the Lambert-Parks House at East Main St., which at some time also became the residence of A.S. Horney.

Summer gowns 1840

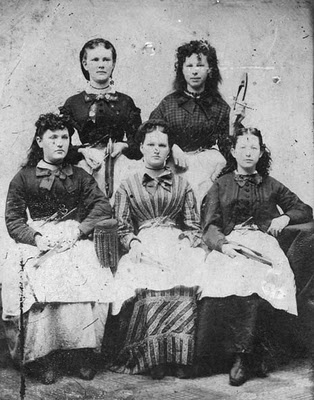

unknown Franklinville girl, circa 1850.

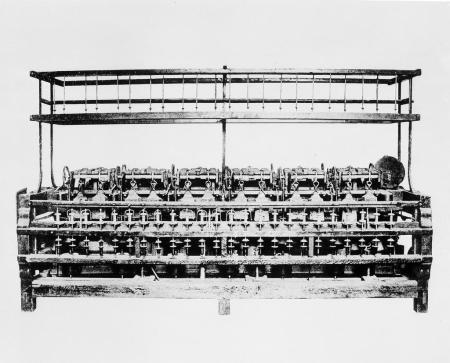

“The Young Ladies, all dressed in white, were arranged in a line”-

The majority of the employees of the factory were women and children, as one important reason for founding the factory in this age was to provide for the social welfare of widows and orphans who had no “breadwinner” to pay their room and board. Though even at this early date women who worked in cotton mills of England were considered debased and lower class, the “mill girls” of New England had a reputation for being intelligent, well-educated and virginal. Even Charles Dickens was shocked at the difference between the mill girls he met at Lowell, Massachusetts, and the slovenly illiterate workers he knew from the British workhouses. The good character and morality of the workers along Deep River was one of the important selling points for the antebellum factory owners in attracting residents and new employees.

Mill Girls from the Weave Room

The historian Holland Thompson, whose mother worked in the mills in Franklinsville, and whose grandfather Thomas Rice was a contractor who built the factories and covered bridge, wrote: “Upon Deep River in Randolph county… the Quaker influence was strong. Slavery was not widespread and was unpopular. The mills were built by stock companies composed of substantial citizens of the neighborhood. There was little or no prejudice against mill labor as such, and the farmer’s daughters gladly came to work in the mills. They lived at home, walking the distance morning and evening, or else boarded with some relative or friend near by. the mill managers were men of high character, who felt themselves to stand in a parental relation to the operatives and required the observance of decorous conduct. Many girls worked to buy trousseaux, others to help their families. They lost no caste by working in the mills.” [Holland Thompson, From the Cotton Fields to the Cotton Mill. MacMillan, 1906]

As the primary product of the factory was white or unbleached cotton “sheeting,” it is probable that the factory provided the raw materials for the dresses and the flags.

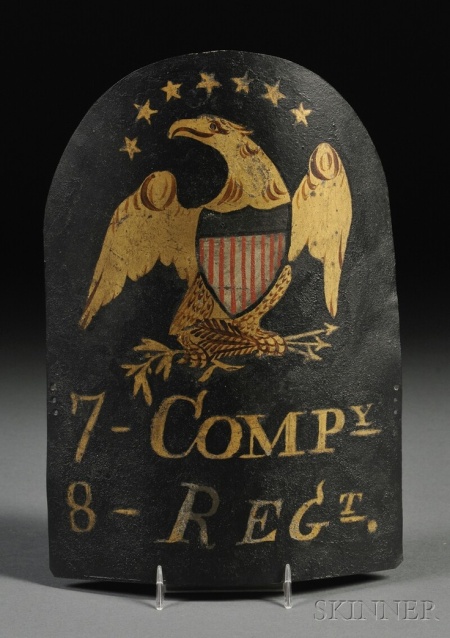

Regimental Flag 2nd Cavalry

“beautiful white Flag”-

It was a tradition for young women of the community to design, sew and present to the militia company a banner which would identify the company when in formation with the battalion. They usually were embroidered with inspirational and patriotic slogans or mottos. In 1861 a group of young ladies presented a similar silk banner to the Randolph Hornets, organized by the Cedar Falls Company to represent both Cedar Falls and Frankinsville. The banners mentioned in this article have been lost, but the Hornets banner is preserved in the Asheboro Public Library.

folk art Quilt

“presented… through James F. Marsh”-

In 1842 James F. Marsh (1920-1902) was evidently the “Agent,” or business manager, of the Cedar Falls Company. He was newly wed, having married Mary Ann Troy (1825-1856 on January 27, 1842. That made him a son-in-law of Franklinsville company President John B. Troy. Marsh founded a business turning wooden bobbins for the factories in Cedar Falls in the later 1840s. The relationship of James F. Marsh and merchant Alfred H. Marsh of Asheboro is unclear. Genealogists state that James F. Marsh was the son of Robert H. Marsh of Chatham County, who has no apparent relationship to Alfred Marsh. But Alred Marsh seems to have treated like a son, whatever their relationship. JA Blair says that the original Cedar Falls partners were Benjamin Elliott, Henry B. Elliott, Phillip Horney, and Alfred H. Marsh. James F. Marsh became a Director of the company in 1847. Marmaduke Robins lived in the former Alfred H. Marsh house in Asheboro, originally containing 52 acres. Sidney Robins says the ell was added to the house for the wedding of “young Jim Marsh” (Robins, Sketches of My Asheboro.) The county issued a Peddler license in 1845 to “Marsh, Elliott & Co.” (Randolph County 1779-1979, p43). Alfred H. Marsh was listed as “merchant” in 1850 & 1860 censuses of Asheboro; he signed on to the 1828 Charter for the Mfg Company of the County of Randolph; was a Trustee of Asheboro Female Academy, 1839 (Southern Citizen, 6-14-39). James F. Marsh moved to Fayetteville around 1850 and was involved in a number of businesses, including a wholesale freighting business with his father in law, a steam boat line on the Cape Fear, and supervising construction of the Fayetteville and Western railroad.

Coffin’s Grove today, at 722 West Main Street, Franklinville.

“proceeded to [the stand at] MR. COFFIN’S Grove, on the opposite hill”-

Mr. Coffin’s Grove was and is at the top of the hill leading up from Walnut Creek, known as Greensboro Road and West Main Street. His house, built about 1835, is now my house. There was an extensive grove of large oak trees, dating back to the 1770s, on the crest of the hill between the house and the school and meeting house across the street. Only two oak trees survive from the grove; 3 have died since I came to town in 1978, and the depressed spots in the yard where several others stood can still be seen. When the property became the home of the Makepeaces, residents began to refer to the “Makepeace Grove,” and the Courier newspaper in the early 20th century still mentions the church having entertainments and ice cream socials in the Makepeace Grove.

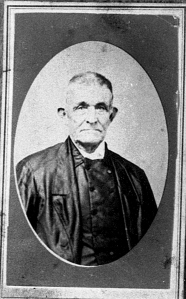

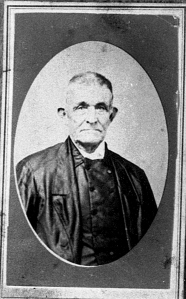

Elisha Coffin, circa 1860.

Coffin’s House, with part of the oak grove, circa 1940.

Elisha Coffin (1779-1871) was a member of the well-known Quaker family of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. His father had emigrated to North Carolina after beginning a career in whaling, and married Hannah Dicks, the daughter of a Quaker preacher. In North Carolina Elisha’s sea-faring father became a miller, and Elisha too learned to follow that trade. In 1807 he married Margaret McCuiston, also perhaps a miller’s child, and also something worse: a Presbyterian. Such an alliance was not sanctioned… Elisha was disowned “for marrying out of Unity.” He was never again officially a Friend, but never does he seem to have strayed far from their influence. This seems to have been especially true in regard to the Friends’ testimony against negro slavery. During the ‘teens and ‘twenties Elisha was several times a delegate to the meetings of the North Carolina Manumission Society, an organization which sought to gradually “manumit,” or free, slaves. At times he took a more active role, according to Levi Coffin, Elisha’s first cousin and the so-called “President” of the Underground Railroad. While he was engaged in purchasing the Franklinville property in the fall of 1821, Levi writes that Elisha, his father and his sister smuggled an escaped slave named Jack Barnes from Guilford County into Indiana, trailed all the while by Levi and the angry slaveowner.

Coffin was presiding Justice of the county court in 1833 and 1834, and was involved in several schemes for the improvement of transportation and education. When pro-slavery investors Led by Hugh McCain took control of the governing board of the Franklinsville factory in 1850, Coffin sold his home and property to George Makepeace, superintendent of the cotton mill. See Deed Book 28, pages 479 and 483. Coffin bought what is now known as “Kemp’s Mill” on Richland Creek about 5 miles south of Franklinville. See Deed Book 28, page 489. His son Benjamin Franklin Coffin lived not far away. Elisha Coffin subsequently seems to have turned back towards the Friends of his youth; in 1857 he sold his rural Randolph County mill and moved back to New Garden in Guilford County, the community of his birth. See Deed Book 30, page 515, Randolph County Registry, and Deed Book 37, page 670, Guilford County Registry. There he ran the college grist mill until his death in 1871.

Fife Drum OSV

“led by their Band of Musicians in the front”-

Milita companies of the time would have had boys playing fife and drums, which were used to keep up a marching rhythm and beat. In a light infantry company, orders were sent by bugle or whistle instead of drum, since the sound of a bugle carries further and it is difficult to move fast when carrying a drum. There were many tunes written and performed by fife and drum bands. “Huzza for Liberty” by George K. Jackson (1796) was rousing song used by militia men on marches. Old Sturbridge Village, which recreates the period of the 1830s and 1840s New England, maintains such a band for regular performances. See the following:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RPd3L5QJQT4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MlBasZfmD2I

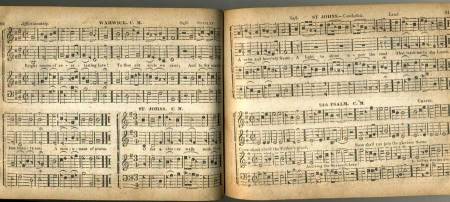

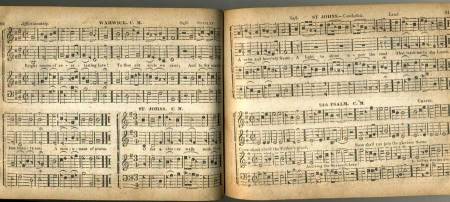

Fa sol La Mi

the Sacred Harp

“a Hymn was read and sung”-

For a hymn to be “read and sung,” it would have been done in an ‘a cappella’ call-and-response manner, as in shape-note singing. In that style of singing a Song Master “sang the notes” pitched to his set of tuning forks; then “read out” the words to the group, line by line, with the group alternately responding by singing the hymn, line by line. The practice of singing music to syllables designating pitch goes back to about AD 1000. Shapes to indicate the tone of a note were developed in New England, and used as early as the 1698 edition of the Bay Psalm Book (first published in 1640 and the first book printed in North America). They were designed to facilitate community singing at a time before hymn books, and for people who could not read standard musical notation. The system that became most popular in the South was the “Sacred Harp” tradition (first published in 1844) of four shapes — triangle-oval-square-diamond– corresponding to the “fa-sol-la-mi” syllables of the C-major scale. After 1846 a seven-shape notation grew in popularity.

The familiar hymns of today were just beginning to be sung in the 1840s. One of the earliest known printings of the tune for “Amazing Grace” is an 1831 shape note hymn book published in Winchester, Virginia. It is titled “Harmony Grove” in The Virginia Harmony and is used as a setting for the Isaac Watts text “There Is a Land of Pure Delight”. The modern “Amazing Grace” text was not set to this melody until the 1847 Southern Harmony, where the tune was called “New Britain”.

For this occasion, I assume that a ‘patriotic’ hymn was the order of the day. “America the Beautiful,” now widely considered as the American patriotic hymn, was not published until 1910. “Chester,” written by William Billings (1746-1800) of Boston and first published in 1771, was unofficially considered the national hymn of the American Revolution, so I offer it in this place:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wqQrWKfLNcw

Minister OSV

“a Prayer delivered by the Rev. MR. HENDRICKS”-

Hendricks must be the person previously referred to as “the Chaplain,” but the “Rev. Mr. Hendricks” is something of a mystery. The “Preacher in Charge” of the Franklinsville Methodist Church from its creation in August 1, 1839 until his transfer in 1847 was T.R. Brame. A John Hendricks was one of the named Trustees of the Franklinsville Methodist Church when Elisha Coffin deeded them land “for a burying ground”, on November 2, 1844.

John Hendricks (1796-1873) was listed as living in Franklinsville (adjoining Elisha Coffin, Leander York, Philip and Alexander Horney) in the census of 1840. In 1817 he was to married Nancy Macon (1800-1853), daughter of Gideon Thomas Macon of the Holly Spring area. Their son Thomas Alston Hendricks (1823-1879) was one of the 15 initial stockholders of the Island Ford mill in 1846. Thomas A. Hendricks md. Permelia Johnson, 1 March 1845, and his bondsman was Dr. Alfred Vestal Coffin. The census of 1840 lists 15 residents of his home, 5 of whom worked in manufacturing. This indicates that he may have operated the factory’s boarding house, although the 1850 census lists 12 family members by name. That census lists John Hendricks occupation as “carpenter” and his son Thomas as “manufacturer.”

The tombstone of Nancy Macon Hendricks in the Franklinsville Methodist cemetery reads “Nancy/ wife of Rev. John Hendricks/ born March 30, 1800/ died March 18, 1853.” There is no other record of John Hendricks as a recorded minister.

Fife Drum OSV2

“A National Air was then played by an excellent Band”-

Our current “National Air” or anthem is of course The Star-Spangled Banner, but it probably was not the song played in this position on the program. President Woodrow Wilson ordered first ordered the SSB to be played at military and naval occasions in 1916, but it was not designated the national anthem by an Act of Congress until 1931. Before that time, “Hail Columbia” had been considered the unofficial national anthem. The words to “Hail Columbia, Happy Land!” were written in 1798 by Joseph Hopkinson (son of Francis Hopkinson, composer and signer of the Declaration of Independence), and set to the tune of “The President’s March,” a tune composed by Philip Phile for President George Washington’s inauguration. ‘Hail Columbia’ is still used as the official song for the Vice President of the United States of America.

Independence Day OSV

“The Declaration of Independence was read”-

[Of course this was the whole point of the day, reminding the crowd of the founding of the country 66 years before.]

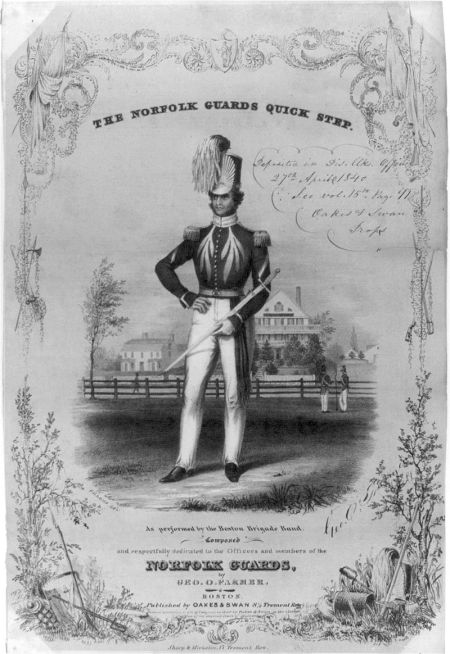

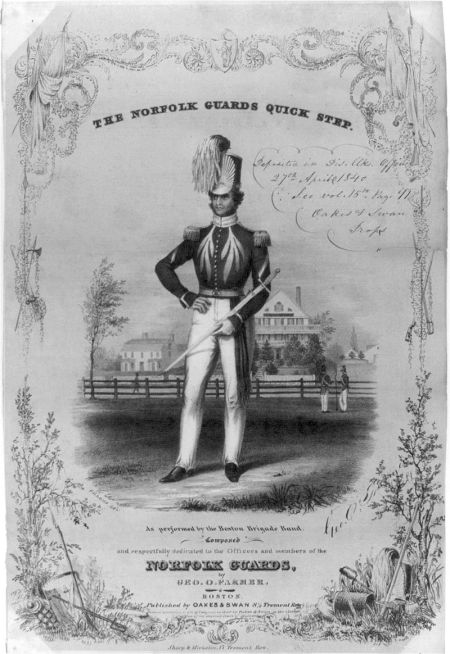

Norfolk Guards QuickStep Sheet Music

“after Music” the Orator spoke-

Whether vocal, instrumental or military, there is a wealth of American Independence Day music that could be inserted here. “The Liberty Song”, written by Founding Father John Dickinson in 1768 and set to the music of William Boyce’s “Heart of Oak” was perhaps the first patriotic song written in America. The song contains the line “by uniting we stand, by dividing we fall…” Others written in the 18th century were “Ode for the 4th of July” and “Ode for American Independence” (1789). “The Patriotic Diggers,” published in 1814 was popular in the period. If it was another ‘patriotic hymn’ read and sung, “The American Star” is a good possibility because it is one of the few non-religious songs published in the original Sacred Harp hymnal (#346, 1844 ed.). The first publication of the song was in an 1817 collection entitled The American Star, which was inspired by the War of 1812 and also included the first printing of the Star Spangled Banner. White and King’s “The Sacred Harp” was first published in 1844, but it was based on William Walker’s “Southern Harmony” (1835).

Henry Branson Elliott, circa 1850

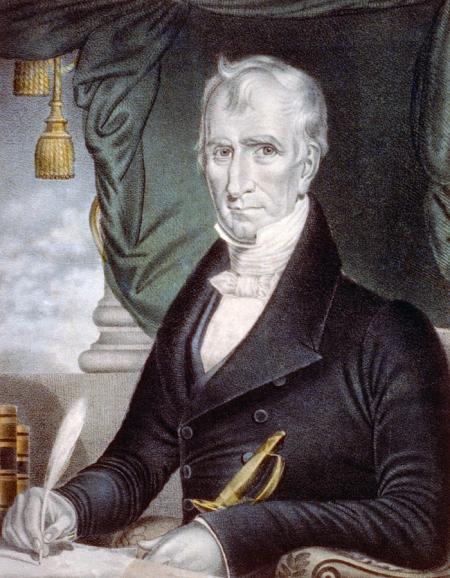

“the Orator Henry B. Elliott”-

Henry Branson Elliott (11 Sept. 1805- 14 Jan. 1863) was one of the most progressive figures in antebellum Randolph County. His father Benjamin Elliott (1781- 27 Feb. 1842) had been Clerk of Superior Court and the commanding Lt. Colonel of the enrolled militia. Elliott graduated from UNC Chapel Hill in 1826 and did post-graduate work at Princeton (Mrs. Laura Worth, History of Central Hotel, August 1940). The Raleigh Register noted on March 14, 1837 that “Messrs. Elliott, Horney and others have been for some time actively engaged in erecting a Cotton Factory at the Cedar Falls on Deep River… we understand they are making rapid progress, and likely to get the machinery into complete operation some time during the prssent spring.” By mid-June the 500-spindle factory was making “superior quality cotton yarn” for sale to hand weavers. (Southern Citizen, 17 June 1837). In November 1838 the Elliotts purchased the ownership interest of the Horneys, who had invested in the factory in Franklinsville (Deed Book 22, Page 89), and in December of that year they sold a one-quarter interest to Alfred H. Marsh, an Asheboro merchant, and their son- and brother-in-law. Elliott was elected to a term in the state Senate in 1833, and campaigned across the state in favor of the first public school referendum in 1839. He served as Clerk and Master in Equity in 1841 while Jonathan Worth campaigned for Congress, and in 1842 was elected to replace Worth in the state Senate. In the Senate Elliott served as chairman of the committee on the State Library, and of the committee “on the subject of a state Penitentiary,” a state-funded prison which was proposed as a progressive alternative to the stocks, pillories, and whipping post. Of his service in the Raleigh Register noted that “Mr. Elliott, of Randolph, is one of those industrious, hard-working members, who, though qualified to shine in debate, seldom occupies the time of the house in displays of that kind, but is content to pursue the even tenor of his way, in discharging the not less useful, but less attractive, duties of a thorough business committeeman.” (Greensboro Patriot, 18 Jan. 1845, quoting Raleigh Register). Elliott continued to own and operate the Cedar Falls factory until a series of financial reverses in the 1850s. He moved his family to Missouri in 1859, and in the census of 1860, his occupation is listed as “Tobacconist.”

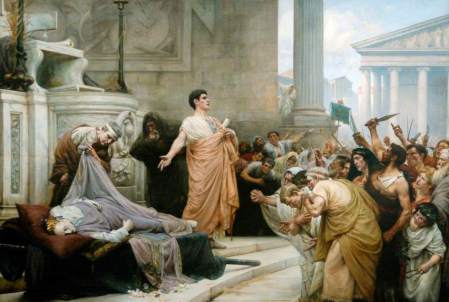

Mark Antony’s Funeral Oration for Caesar (c) Hartlepool Museums and Heritage Service; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

As a candidate for the state Senate, it was natural for Henry Branson Elliott to agree to speak to such a crowd, even at short notice (the speech was “hastily prepared”). As a graduate of the state university and of Princeton, Elliott would have been familiar with preparing and delivering classical orations as a normal and typical part of the educational process. Even in modern classrooms the oratorical model is still used as a persuasive model for argumentative papers. The text of Elliott’s speech is unknown, but its format would have been clear to every educated man in 1842. Any classical oration consists of six parts:

Exordium: The introduction

Narratio: Which sets forth facts of the case.

Partition: Which states the thesis of an argument

Confirmatio: Which lays out and supports the argument

Refutatio: Which examines counter arguments and demonstrates why they aren’t compelling.

Peroratio: Which resolves the argument and makes conclusions.

[http://www.public.coe.edu/wac/classicalessay.htm ]

Orations were a staple of antebellum Independence Day celebrations. One of the most famous was delivered by the lawyer Francis Scott Key (1779-1843), in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol on the 4th of July, 1831. The author of the poem “The Star Spangled Banner” addressed a city divided by the policies of President Andrew Jackson and counseled moderation and a focus on the history of the day. “The spectacle of a happy people, rejoicing in thankfulness before God and the world for the blessing of civil liberty,” said Key, “ is no vain pageant.”

Another historically significant oration took place on the same day at nearly the same time that Elliott was speaking in Franklinsville. Horace Mann (1796-1859), educator and statesman delivered the annual oration at Fanueil Hall in the city of Boston, on July 4, 1842. Mann broke with the traditional oratorical expectation that the speaker would glorify America, and instead stressed the importance of educational reform and the principle that effective self-government depended on a well-educated populace. Mann’s oration runs to 44 printed pages, printed as part of a July 4th tradition that began in 1783 and continues to this very day.

https://archive.org/details/orationdelivered00mann

Shape Note Choir

“A patriotic Song was then sung by a Choir of Ladies and Gentlemen selected for the purpose”-

As distinct from the hymn “read and sung” by the entire crowd, this was apparently a group concert performance. I submit that the appropriate ‘patriotic song’ here would have been “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee”, also known as “America”, which served as one of the de facto national anthems of the United States during the 19th century. Its lyrics were written by Samuel Francis Smith, and the melody used is the same as that of the national anthem of the United Kingdom, “God Save the Queen.” The song was first performed in public on July 4, 1831, at a children’s Independence Day celebration in Boston. It was first published in 1832. Interestingly for the anti-slavery background of the Franklinsville crowd was that additional verses of an Abolitionist nature were written by A. G. Duncan in 1843. Jarius Lincoln, [ed.] Antislavery Melodies: for The Friends of Freedom. Prepared for the Hingham Antislavery Society. Words by A. G. Duncan. (Hingham, [Mass.]: Elijah B. Gill, 1843), Hymn 17 6s & 4s (Tune – “America”) pp. 28–29.

$10 gold piece

“the following Resolutions were offered”-

A resolution is an official written expression of the opinion or will of a deliberative body, proposed, considered under debate and adopted by motion. To modern politicians resolutions have become a rote and usually pointless part of the parliamentary process which merely states something obvious and has no legal impact or meaning. But in antebellum America the process of considering a voting upon a resolution, even as simple and seemingly pointless as this one thanking the speaker for his address and the village for its hospitality, was a vital and important part of the Independence Day celebration.

Why? Because the Declaration of Independence itself was actually the Resolution of Independence, ratified by the Continental Congress in 1776 as a public statement by the 13 American colonies expressing their consensus that they were now independent of the British Empire. What became known as the “Lee Resolution” was was an act of the Second Continental Congress first proposed by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia on June 7, 1776. Jefferson’s draft of a formal declaration was presented to Congress for review on June 28. Lee’s resolution was actually adopted on July 2, 1776; Jefferson’s edited Declaration for final signing on July 4.

The process of adopting the sense of the assembly in the form of resolutions was a reminder to all attending of the process and procedure of democracy. Even though the civics lessons were part of formal schooling, going through the formal process of proposing and adopting resolutions was a tangible reminder, at least annually, of the mechanics of government.

“by John B. Troy, Esq.”-

“by John B. Troy, Esq.”-

Likewise, appointing a committee to complete additional business of the meeting was a another part of formal parliamentary procedure.

John Balfour Troy of Troy’s Store (now Liberty) was the grandson of Revolutionary War hero and martyr Colonel Andrew Balfour. He made an extensive investment in the founding of the Franklinsville factory and was elected President of the company. Troy was a Steward of Bethany Church near Liberty, built on the site of the former “Troy’s Camp Ground.” His son-in-law James F. Marsh was already on the program; his other son-in-law J.M.A. Drake was one of the founding Trustees for the Frankinsville Methodist Episcopal Church. James Murray Anthony Drake (ca. 1812-?) was a lawyer and married Eliza Balfour. Drake later served as county jailer and operated a hotel in Asheborough.

“John R. Brown”-

“John R. Brown”-

Apparently this was John R. Brown (17 Jan. 1811 – 30 October 1857), son of Samuel Brown (1762-1843), both residents of the Holly Spring Friends Meeting community. Brown was one of the 15 signers of a petition to the Randolph County court dated January 8, 1842, which attested that William Walden and his four sons, “free persons of colour” and residents of the county, were of good character and were recommended to be allowed to carry fire arms. [Randolph County, 1779-1979, p. 73.]

“Wm. J. Long” –

William John Long received a degree from UNC Chapel Hill in 1838; born in Randolph County in 1815, he was the son of Congressman John Long of Long’s Mills, north of Liberty. A lawyer, he served as a member of the General Assembly in 1861. He died in Minneapolis, MN in 1882. His brothers were James Allen Long (1817-1864) UNC AB 1841, a “journalist,” and John Wesley Long (1824-1863) UNC AB 1844, MD, Univ. PA.

Dinner on the grounds

“A large number set down to a sumptuous dinner, prepared by MR. HENDRICKS, and many others shared the hospitality of the Citizens of the place.”-

With 1500 people in attendance, I am assuming that perhaps only the invited guests who took part in the program were fed by Hendricks (perhaps in his boarding house?) Everyone else would have scattered all over town. There is no indication that there was a massive outdoor barbecue or “ox roast,” but that is a possibility.

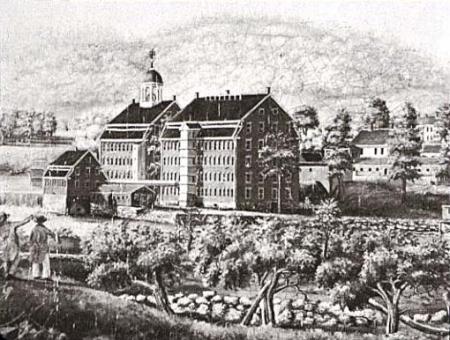

the upper Mill, circa 1875

“The Factory building is a large and imposing brick edifice.”

The three-story factory was modeled on the typical “Rhode Island Plan” factories of New England. It must have been imposing to the visitors, as it was larger than the courthouse or any church in the county. Both the factory and the Coffin mansion were built of brick made in the village. The foundations of the factory, and the “Picker House” where bales of cotton were opened, were made of stone quarried from the bluff at the mouth of Bush Creek. No larger factory was built until the Cedar Falls mill was remodeled in 1847, and the “Union Factory” (now Randleman) was built in 1848. The Island Ford factory (1846) and the Columbia Factory (Ramseur, 1850) were about the same size.

Boston Mfg Co.mill at Waltham, Mass., shows the type of dormer windows used on the Franklinsville factory.

“between the dormant windows”-

This is an archaic form of the word “dormer;” referring to the small windows which lit the fourth or attic floor of the mill. In 1806, the British House of Commons paid for repairs to the slates, “valleys and flashings to dormant windows” of Dr. Stevens’s Hospital (Journals of the House of Commons, Vol. 61, p755)

Accounts of the April, 1851 fire that destroyed the factory noted that the fire began on this floor of the mill, in the “Dressing Room.” The dressing machine (later called the “slasher”) was a machine that brushed hot starch, or “sizing,” on the cotton yard which was to be used as warp in the looms. The liquid starch was then dried by hot air or steam, meaning that a source of heat had to be present.

Folk Art flag

“a white flag…upon which was painted a large Eagle… protector… of industry”-

The American Eagle was perhaps the most common motif in early American political art. Early labor unions often portrayed an Eagle draped in or “guarding” a flag and gear wheel, to indicate that America protected and supported its nascent industries.

Temple of Venus and Rome

“the lamp of freedom… the sacred altar of liberty… more favorable auspices…”-

The flowery language of the final two paragraphs was a very common peroration or exhoration in public speech of the time, and might even have been copied from Henry B. Elliott’s oration of the day. All of the images were intended to invoke the history, mystery and splendor of Imperial Rome, very familiar to the audience from school lessons. “Taking the auspices,” for example, referred to the process which a civil priest, the Augur, interpreted signs and omens from the observed flight or internal organs of birds. The Roman historian Livy stresses the importance of the Augurs: “Who does not know that this city was founded only after taking the auspices, that everything in war and in peace, at home and abroad, was done only after taking the auspices?” The general sense is all that omens indicate a bright future for the United States as long as the present generation respects previous generations such as those who signed the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence in Charlotte in 1775, or Herman Husband of Liberty and his fellow tax protestors who fought the War of the Regulation at Alamance Battleground in 1771.

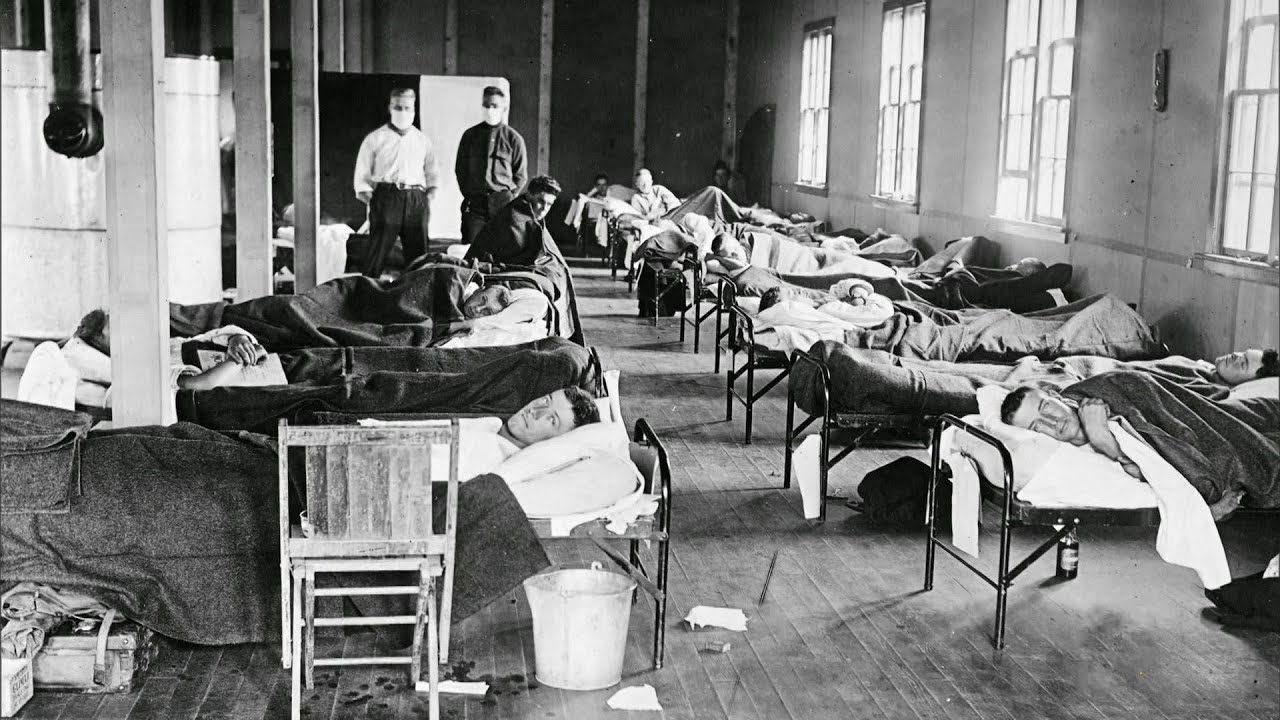

The worst pandemic to hit the United States before COVID-19 was the “Spanish” influenza epidemic that followed the end of World War I. The parallels between that epidemic of one hundred years ago and today are striking, and show both how American society has advanced and regressed.

The worst pandemic to hit the United States before COVID-19 was the “Spanish” influenza epidemic that followed the end of World War I. The parallels between that epidemic of one hundred years ago and today are striking, and show both how American society has advanced and regressed.

The difference with the influenza of 1917/18 (now called the Influenza A Strain) was that it triggered a virulent reaction in the immune system of those who were strongest- those twenty to forty years old, young and fit; in many cases it killed in less than 48 hours from first fever to last breath. As its victims’ lungs filled with fluid and their respiratory systems failed, their skin, starved for oxygen, turned blue- giving the tabloid headline name the “Blue Death” to the new influenza.

The difference with the influenza of 1917/18 (now called the Influenza A Strain) was that it triggered a virulent reaction in the immune system of those who were strongest- those twenty to forty years old, young and fit; in many cases it killed in less than 48 hours from first fever to last breath. As its victims’ lungs filled with fluid and their respiratory systems failed, their skin, starved for oxygen, turned blue- giving the tabloid headline name the “Blue Death” to the new influenza.

“In appearance one is struck by the fact that the patient looks sick. His eyes and the inner side of his eyelids may be slightly “bloodshot” or “congested,” as the doctors say. There may be running from the nose, or there may be some cough. These signs of a cold may not be marked; nevertheless, the patient looks, and feels very sick….

“In appearance one is struck by the fact that the patient looks sick. His eyes and the inner side of his eyelids may be slightly “bloodshot” or “congested,” as the doctors say. There may be running from the nose, or there may be some cough. These signs of a cold may not be marked; nevertheless, the patient looks, and feels very sick….

But the same edition of the paper showed that local people were dying.

But the same edition of the paper showed that local people were dying. Dr. Edward Kidder Graham, eighth president of the University of North Carolina, and a prominent educational figure in the nation, died last Saturday night at his home, Chapel Hill, from pneumonia following an attack of Spanish influenza. Dr. Graham had been ill less than a week, the disease assuming the most malignant type and turning to the dread pneumonia in two or three days. The funeral was held at Chapel Hill, Monday afternoon. There was no service at the church or home, but a simple service at the grave… All work at the University was suspended for the day and the faculty and students attended the funeral in a body. [The Courier, 10-31-18, p7. Marvin Hendrix Stacy, the chairman of the faculty, became the acting university president after Graham’s death. On 21 January 1919, Stacy also

Dr. Edward Kidder Graham, eighth president of the University of North Carolina, and a prominent educational figure in the nation, died last Saturday night at his home, Chapel Hill, from pneumonia following an attack of Spanish influenza. Dr. Graham had been ill less than a week, the disease assuming the most malignant type and turning to the dread pneumonia in two or three days. The funeral was held at Chapel Hill, Monday afternoon. There was no service at the church or home, but a simple service at the grave… All work at the University was suspended for the day and the faculty and students attended the funeral in a body. [The Courier, 10-31-18, p7. Marvin Hendrix Stacy, the chairman of the faculty, became the acting university president after Graham’s death. On 21 January 1919, Stacy also

The second wave of flu had disappated by May, 1919, but then reappeared full blast in the winter of 1920. “For more than two weeks the epidemic of influenza has been in full blast at Coleridge. Practically everybody in the town has had it, there being more than 250 cases. Up to date only two deaths have occurred, that of Mrs. L. B. Davis, and Mrs. A.M. Poole. Mrs. Davis died the latter part of last week. She was 35 years of age, and a daughter of the late Gurney Cox. At the time of Mrs. Davis’ death her husband was seriously ill with influenza. Mrs. A.M. Poole was a daughter of Mr. W.A. Poole, of Coleridge. She is survived by her husband and three children.” [The Courier, 5 Feb 1920, pg1.]

The second wave of flu had disappated by May, 1919, but then reappeared full blast in the winter of 1920. “For more than two weeks the epidemic of influenza has been in full blast at Coleridge. Practically everybody in the town has had it, there being more than 250 cases. Up to date only two deaths have occurred, that of Mrs. L. B. Davis, and Mrs. A.M. Poole. Mrs. Davis died the latter part of last week. She was 35 years of age, and a daughter of the late Gurney Cox. At the time of Mrs. Davis’ death her husband was seriously ill with influenza. Mrs. A.M. Poole was a daughter of Mr. W.A. Poole, of Coleridge. She is survived by her husband and three children.” [The Courier, 5 Feb 1920, pg1.] During the 1920 epidemic, the Fletcher Bulla recommended 9 suggestions for good public health. Some show that some major improvements have occurred in a century-

During the 1920 epidemic, the Fletcher Bulla recommended 9 suggestions for good public health. Some show that some major improvements have occurred in a century-

I am writing this from my home in Franklinville, NC, in the midst of COVID-19 self-isolation. For most of America, home isolation is designed to “flatten the curve”- to impose community isolation measures that slow the spread of infection and keep the daily case load at a manageable level for our existing health care resources. In my case, it’s to protect me in the wake of my recent heart surgery, and keep me from the risk of pneumonia on top of asthma and post-anesthesia breathing issues.

I am writing this from my home in Franklinville, NC, in the midst of COVID-19 self-isolation. For most of America, home isolation is designed to “flatten the curve”- to impose community isolation measures that slow the spread of infection and keep the daily case load at a manageable level for our existing health care resources. In my case, it’s to protect me in the wake of my recent heart surgery, and keep me from the risk of pneumonia on top of asthma and post-anesthesia breathing issues.

Miss Kitty Caviness, a retired teacher, first told me about Franklinville Pest House, which was in the hollow between her house and the Lower Mill. It was a small cabin or “fever shed” with beds, and if the illness was something that could endanger the whole village, the patient was taken there under quarantine. I never saw the building; as far as anyone could remember, the Franklinville Pest House was last used during the “Spanish Flu” epidemic of 1918-1920. “It smelled like sulpher,” said Miss Caviness, and undoubtedly this was due to the common practice of the time of disinfecting the air by burning sulpher in open pans in each room.

Miss Kitty Caviness, a retired teacher, first told me about Franklinville Pest House, which was in the hollow between her house and the Lower Mill. It was a small cabin or “fever shed” with beds, and if the illness was something that could endanger the whole village, the patient was taken there under quarantine. I never saw the building; as far as anyone could remember, the Franklinville Pest House was last used during the “Spanish Flu” epidemic of 1918-1920. “It smelled like sulpher,” said Miss Caviness, and undoubtedly this was due to the common practice of the time of disinfecting the air by burning sulpher in open pans in each room. I’m told that Randleman also had a Pest House, perhaps shared with Worthville, and this may have been a feature of all the Deep River Mill villages. Universal vaccination for communicable deadly diseases gradually did away with the need to isolate patients from their neighbors, but the sudden rise of the “Spanish Flu” in 1918 brought them back into wide use for a few years- and triggered a movement to build community hospitals in rural areas.

I’m told that Randleman also had a Pest House, perhaps shared with Worthville, and this may have been a feature of all the Deep River Mill villages. Universal vaccination for communicable deadly diseases gradually did away with the need to isolate patients from their neighbors, but the sudden rise of the “Spanish Flu” in 1918 brought them back into wide use for a few years- and triggered a movement to build community hospitals in rural areas.

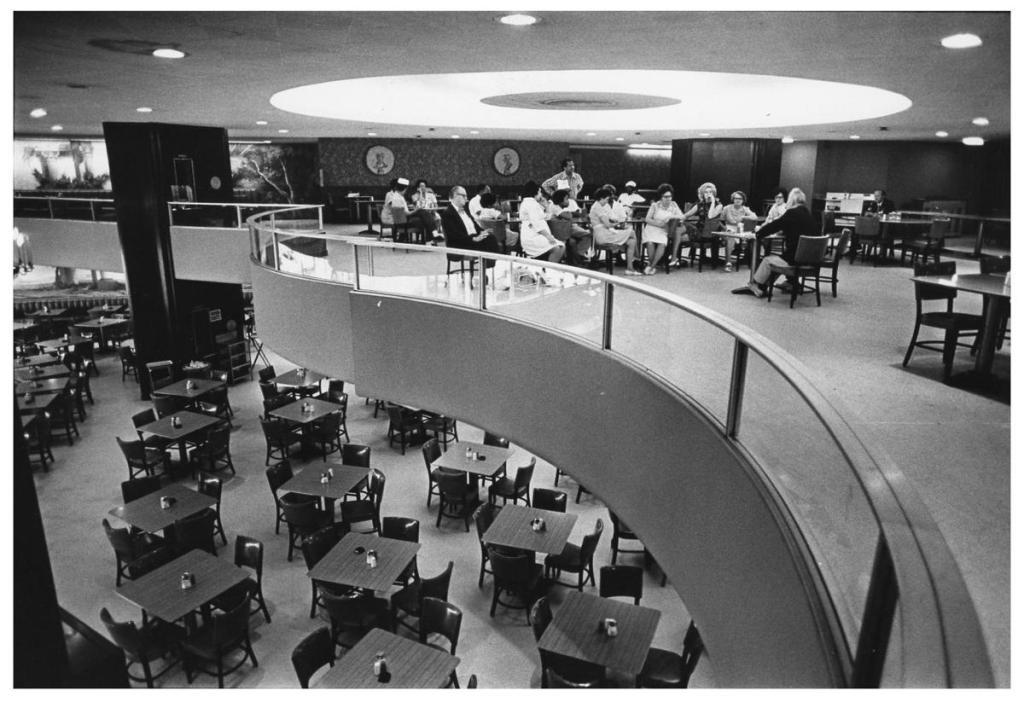

Recovery in the ICU is measured not just by walking and talking, but in getting tubes and wires removed day after day. The electrocardiogram leads were the first I got, 8 of them even before surgery (another 8 during surgery, which came off Friday). Then there were IVs in both wrists, one in the left arm and one in the groin, which came out pretty soon. There were left and right chest tubes, to drain post-operative blood and fluid from the operation site. There was a Foley catheter, so I didn’t have to get out of bed to pee. And there was the “Central Line,” on the right side of my neck, a large IV-type tube that went straight into an artery and had about half a dozen other tubes branching out of it for various purposes. That, my sister said, was the thing that looked the worst.

Recovery in the ICU is measured not just by walking and talking, but in getting tubes and wires removed day after day. The electrocardiogram leads were the first I got, 8 of them even before surgery (another 8 during surgery, which came off Friday). Then there were IVs in both wrists, one in the left arm and one in the groin, which came out pretty soon. There were left and right chest tubes, to drain post-operative blood and fluid from the operation site. There was a Foley catheter, so I didn’t have to get out of bed to pee. And there was the “Central Line,” on the right side of my neck, a large IV-type tube that went straight into an artery and had about half a dozen other tubes branching out of it for various purposes. That, my sister said, was the thing that looked the worst. The things that felt the worst, though, were those chest tubes. I’m sure my body was in some shock from the chest cutting and etc., but as I discovered, there was a morphine drip, and soon, Oxycodone taking the edge off that. But the chest tubes interfered mightly with breathing, and rehab people were very insistent on me breathing. Not that I wasn’t; a lifetime of asthma has taught me to be very aware of my breathing; but these tubes made it amazing difficult to breathe deeply or cough. (Or, God Forbid, to sneeze!) As if this wasn’t bad enough, what turned out to be my only major complication started Saturday afternoon and continued all through Sunday- burps, belches and hiccups. That doesn’t sound so bad, you say? Well, as I learned, when you’re cut open for hours laying on your back in the operating room, air gets into places in your body where air doesn’t normally go, and sooner or later it has to come out. Also, while open heart surgery doesn’t usually go anywhere near the diaphragm, which is a major breathing muscle behind the navel, the chest tubes to poke around in there and irritate it. And when the diaphragm is irritated, sometimes in some people, it responds with hiccup spasms. I was one of those lucky people. The older nurses knowingly said this often happened with women who get C-sections, and there is little to do short of Haldol, usually used to treat schizophrenia. Since I’d already had my first brush with all the scheduled pain killers I used to talk about in criminal court, I decided to avoid the Haldol. But dealing with those hiccups was agony, as every upheaval felt like I was about to pop open my chest stitches.

The things that felt the worst, though, were those chest tubes. I’m sure my body was in some shock from the chest cutting and etc., but as I discovered, there was a morphine drip, and soon, Oxycodone taking the edge off that. But the chest tubes interfered mightly with breathing, and rehab people were very insistent on me breathing. Not that I wasn’t; a lifetime of asthma has taught me to be very aware of my breathing; but these tubes made it amazing difficult to breathe deeply or cough. (Or, God Forbid, to sneeze!) As if this wasn’t bad enough, what turned out to be my only major complication started Saturday afternoon and continued all through Sunday- burps, belches and hiccups. That doesn’t sound so bad, you say? Well, as I learned, when you’re cut open for hours laying on your back in the operating room, air gets into places in your body where air doesn’t normally go, and sooner or later it has to come out. Also, while open heart surgery doesn’t usually go anywhere near the diaphragm, which is a major breathing muscle behind the navel, the chest tubes to poke around in there and irritate it. And when the diaphragm is irritated, sometimes in some people, it responds with hiccup spasms. I was one of those lucky people. The older nurses knowingly said this often happened with women who get C-sections, and there is little to do short of Haldol, usually used to treat schizophrenia. Since I’d already had my first brush with all the scheduled pain killers I used to talk about in criminal court, I decided to avoid the Haldol. But dealing with those hiccups was agony, as every upheaval felt like I was about to pop open my chest stitches. Gradually they became less frequent and finally stopped; One chest tube came out Sunday; the other on Monday, and that helped with the hiccups and breathing. Gradually my kidneys started to work again and get more of the meds and anesthetic out of my system. This was important as they had given my lots of IV fluids for several days, and when I finally weighed on Sunday I was 17 pounds heavier than when I went into the hospital- all water, they said, as I wasn’t really eating. On Monday that began to balance out, as diarrhea showed my digestion getting back in the game and eliminating lots of water at the same time.

Gradually they became less frequent and finally stopped; One chest tube came out Sunday; the other on Monday, and that helped with the hiccups and breathing. Gradually my kidneys started to work again and get more of the meds and anesthetic out of my system. This was important as they had given my lots of IV fluids for several days, and when I finally weighed on Sunday I was 17 pounds heavier than when I went into the hospital- all water, they said, as I wasn’t really eating. On Monday that began to balance out, as diarrhea showed my digestion getting back in the game and eliminating lots of water at the same time. So I’m on the mend from open-heart surgery in the COFID-19 plague year, trying to heal up, deal with seasonal allergies that also limit breathing, and trying very hard not to get the virus that can lead to pneumonia. Hard enough to recover from one of the most major invasive surgeries, but now I must worry about an even worse problem potentially arising from every social interaction, Amazon delivery or grocery store visit. I’ve seen three actual people in the last week, one of whom took out the last chest tube stitches.

So I’m on the mend from open-heart surgery in the COFID-19 plague year, trying to heal up, deal with seasonal allergies that also limit breathing, and trying very hard not to get the virus that can lead to pneumonia. Hard enough to recover from one of the most major invasive surgeries, but now I must worry about an even worse problem potentially arising from every social interaction, Amazon delivery or grocery store visit. I’ve seen three actual people in the last week, one of whom took out the last chest tube stitches.