Randolph County’s heritage of resistance to secession and support of the Red String has been amply documented by the late, lamented Bill Auman in his book The Civil War in the North Carolina Quaker Belt. But the stories of those opposed to the war have not been documented with as much attention to detail as those who enlisted and served in the army of the Confederate States. Wally Jarrell’s The Randolph Hornets in the Civil War is a meticulous history of Company M of the 22nd NC Infantry Regiment, one of three Randolph County companies in that regiment. [i]

The most complete roster of Randolph County’s Confederate veterans was compiled by Gary D. Reeder of Trinity, and published in The Heritage of Randolph County, North Carolina (Vol. 1), published in 1993 but now out of print. Reeder found records of 1,921 individuals who served with the Confederate forces, but does not consider that an exhaustive list. Eighty-six of those were with Robert E. Lee at Appomatox, and 132 others signed the Oath of Allegiance in Greensboro after the end of hostilities.

One hundred of those were killed in battle; 7 were reported as missing in action; 74 died of wounds; 345 died of disease. 616 were prisoners of war, and 76 of those died while interned. 489 were wounded; 73 of those were wounded twice; 12 were wounded 3 times and two, four times.[ii]

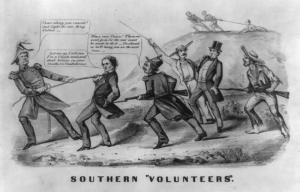

Not all of those who served did so willingly. Bill Auman points out that Randolph County in 1861 had the third-lowest volunteer rate in the state. The enlistment rate for North Carolina as a whole was 23.8%; in Randolph it was 14.2%. As the war went on, conscription acts were passed by the CSA to force men into service; 40% of the state’s draftees in 1863 came from the recalcitrant Quaker Belt counties, with Randolph contributing 2.7% of its population to the draft that year. North Carolina as a whole contributed about 103,400 enlisted men to the Confederate Army, about one-sixth of the total, and more than any other state. But this does not mean those troops were all loyal Confederates; about 22.9% (23,694 men) of those troops deserted, a rate more than twice that of any other state.

The Confederacy did not publish statistics on desertion, but Reeder states that at least 320 of Randolph’s nearly 2,000 men deserted from their regiments, with 32 deserting twice, five deserting three times and one deserting five times! Forty-four of these deserters were arrested, 42 were court-martialed, and at least 14 were executed. 196 captured Confederates took the Oath of Allegiance to the Union before the end of the war, with 67 joining the Union Army.[iii] These new Union recruits were derisively called “Galvanized Yankees” by their old comrades.

As the Confederacy was gradually mythologized and romanticized after the war, a history of desertion, however well supported by friends and family during the war, was not a heritage that was proudly maintained even in Randolph County. Certainly we never hear anyone boasting about their Galvanized Yankee ancestors. But the fact remains that many of those who served, served involuntarily.

A case in point is the service history of Frank Toomes. William Franklin Toomes (Jr.) was born October 25, 1838 in the Sumner community of Guilford County, less than a mile north of the Randolph County line. He was the son of William F. Toomes (b. 1808) and Sarah (“Sallie”) Jenkins (b. 1812). The elder Toomes was a blacksmith. In his Apprentice Indenture, dated August 25, 1824, Abraham Delap agreed to teach William “to read, write, & cipher thro the Rule of Three, and learn the Blacksmith Trade and give him a sett of Tools at $55” when he reached the age of 21 years. Well before that time there were problems between apprentice and master, as seen in the advertisement placed in the Greensboro Patriot of October 11, 1825 by Delap: “Ranaway from the subscriber, three apprentices to the Blacksmith’s Business, named William Toombs. Willis Parish and Henderson Parrish…” [iv]

According to family tradition, Frank followed his father into the blacksmithing trade, and when the Civil War broke out, both of them were working as blacksmiths in Cedar Falls or Franklinsville. (The wartime pay records of the Cedar Falls factory exist but do not show either Toomes as an employee, so they must have worked at the nearby Franklinsville or Island Ford factory downstream.) As blacksmiths, the Toomeses would have been exempt from conscription when the Confederacy first established the draft in April, 1862. Male employees of the Deep River cotton mills and ironworks qualified as exempt “indispensable” employees until late in the war. No lists of cotton mill exemptions are known, but one for the Bush Creek Iron Works in Franklinsville exempts 30 male employees. Exemptions were granted (or not) by the regional Enrolling Officer, who at some point decided the cotton mill could do without one of its blacksmiths. Again according to family tradition, when the Enrolling Officer came to the mill, Frank Toomes would hide, submerged in the mill race, breathing through a straw until the coast was clear.

On December 2, 1863 (perhaps when it was too cold for a swim), Frank Toomes was discovered; he was forcibly drafted into Company E of the 58th North Carolina Infantry regiment on December 25, 1863 at Camp Holmes in Raleigh.[v] Within days Toomes must have been sent to the western front, because his very meager Confederate record bears the single remark, “Deserted Jan. 10, 1864, near Dalton.” [vi]

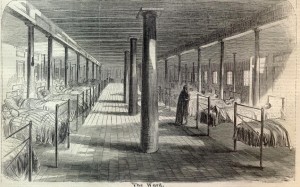

On or around February 1, 1864, 23-year-old Frank Toomes entered the Union lines, surrendered and was taken prisoner to Nashville. On February 12th, he took the Oath of Allegiance to the United States and was assigned to Company H of the 10th Tenn. Cavalry regiment. Within a week, Toomes was hospitalized with the measles- at that time, a life-threatening disease. Toomes was admitted to Hospital No. 19, where he recuperated until February 25, when he was transferred to Bed #61 of “G.H.” (General Hospital) No. 8, for treatment of scurvy.

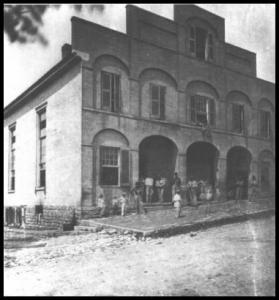

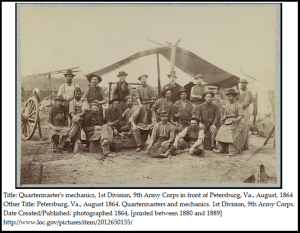

Occupied by Federal forces in 1862, Nashville had become a major resupply center for the Union army, with numerous railroad, blacksmith and transportation units. At least 24 separate military hospitals had been created from the comandeered public buildings of the city, each with a specialty. Number 11, for example, was the “Pest House” (720 beds for contagious smallpox patients). Number 16 was reserved for the U.S. Colored Troops, and Number 17 for Officers. Those hospitals were well documented at the time by photography, and in modern times by the Internet.

First Presbyterian Church at the corner of 5th and Church Sts. in Nashville was one of 3 buildings of Hospital No. 8. It had 206 beds.

A visitor in 1864 wrote “The Masonic Hall and First Presbyterian Church [and the smaller Cumberland Presbyterian Church] constitute Hospital No. 8… As we enter the Hall, we find a broad flight of stairs before us, and while ascending, perceive this caution inscribed upon the wall in evergreen: ‘Remember you are in a Hospital and make no noise.” up this flight… other cautions meet us, such as ‘No Smoking Here” – “Keep Away from the Wall,’ &c.”

The 540 beds of Hospital No. 8 were under the supervision of Medical Director Dr. R. R. Taylor, originally a surgeon with the 4th Iowa Cavalry. Miss Annie Bell was the Matron (nurse) of the Hospital.

Private Toomes was “transferred to Louisville,” on April 6, 1864, where he recuperated at Brown General Hospital (a 700 bed unit) until he returned to his unit in May.

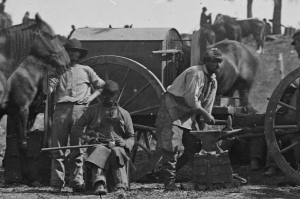

It isn’t clear what duties Pvt. Toomes may have had, but it is possible that he was one of the regimental blacksmiths. A cavalry unit traveled with a portable forge, as horses needed constant hoof care and shoe replacements.

The 10th Tennessee Cavalry was organized and began recruiting in August 1863. Company H mustered in on February 12, 1864, formed of “men mostly from other states.” [vii] It was under the command first of Capt. Jonathan Haltall, and then of Capt. J.L.N. Bryan. The regimental history says-

“During the summer and fall of 1864, it was engaged in arduous duty in Tennessee. Late in the fall [Oct. 13] it was sent to northern Alabama, to watch the movements of Hood’s army, and had an engagement with a largely superior force of Rebels at Florence [October 30; 4 other Union regiments were engaged at nearby Muscle Shoals and Shoal Creek at the same time]. Overpowered by numbers, it was compelled to fall back to Nashville. [where it was on the front lines at the Battle of Franklin, Nov. 30.] On the first day’s battle before Nashville [Dec. 15, 1864, when Hood tried to break Sherman’s supply line from the city], it lost severely in officers and men.” The four-day Battle of Nashville was also a debacle for Hood, marking the effective end of the Army of Tennessee.

The Regiment spent the winter of 1865 in camp at Gravelly Springs, Alabama, and the conduct of some of its men at that time shows that the unit must have been a tough and unruly group. Brig. General Richard W. Johnston, commander of the 6th U.S. Division, reported from Fayetteville, TN, on February 8, 1865 that “The troops under my command have killed 18 guerillas and captured 12 since my arrival here, not counting a number of men belonging to the 10th and 12th Tennessee Cavalry Regiments (U.S.A), who had deserted and become guerrillas of the worst type, who have been captured and forwarded to their regiments.”

The 10th Tenn. moved to Vicksburg, Miss., in February; was sent to New Orleans in March, and was in Natchez until May. It returned to Nashville June 10, 1865. [viii]

Frank Toomes apparently became a good soldier with the 10th Tennessee, as he was promoted to 1st Duty Sergeant of Company H on July 16, 1864. His file for December 1864 notes that Sgt. Toomes had “Lost 1 Army Revolver @ $2.00.”

Toomes was promoted to “QM Sgt” (Quartermaster Sergeant) on June 30, 1865. When the regiment was mustered out of service on August 1, 1865, Toomes’ pay for the year (he had last been paid on December 31, 1864) was $275.00, after deductions made for his uniform and clothing.

Toomes made his way back to Guilford County, where on September 5 1867, he married Susan Thompson. [Marriage Bond Book 03, Page 451]. His wife must have died within the next two years, for the census of 1870 finds Frank Toomes living with his brother Alpheus. Alpheus Toomes and his young family were close neighbors to George Watson Petty (b. 1837), another farmer living near Westminister Post Office, Sumner Township, Guilford County.

House built on Branson Mill Road, Level Cross, NC, by R.V. Toomes, 1924-25.

In 1874 Frank Toomes travelled west to Howard County, Indiana, well beyond the battlefields of 1864, where he married again, to Annie E. Davis (b. 1858) on May 17, 1874. On their return to North Carolina, Frank and Annie settled in the Level Cross community of New Market Township of Randolph County, no more than 2 miles south of his brother, where they had ten children. Frank carried on blacksmithing, farming, and distilling to provide for his family. He was successful enough to loan money to neighbors who needed help buying property (see Randolph Deed Book 100, Page 437, where in May 1895, he loans $60 to buy 11 acres).

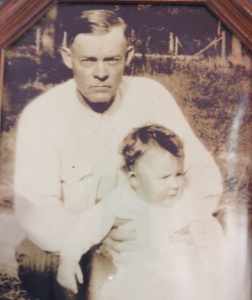

Frank Toomes died February 21, 1913, 49 years after deserting one army and joining another. His son Robert Vernon (“Bob”) Toomes (24 Feb. 1886- July 8 1945) followed family distilling business. In 1924 he built a modern “bungalow” house on Branson Mill Road in Level Cross for his wife Allie Hodgin (1888-1947) and their eight children. Bob and Allie Toomes’ daughter Elizabeth (1917-2006) married Lee Arnold Petty (1914-2000), a grandson of George Watson Petty of Sumner Township. Lee Petty and Frank Toomes’ great-grandsons Richard Lee Petty (b. July 2, 1937) and Morris Elsworth Petty (b. 22 March 1939) are all members of the NASCAR Hall of Fame.

SOURCE NOTE: When I say “family tradition,” that indicates the information came from the family’s historian Howard Toomes, son of William Howard Toomes, brother of Elizabeth and grandson of Frank Toomes. Family photos and more information came from Brenda Toomes Williams and Rose Toomes Luck (daughters of Frank’s son Ralph V. Toomes), all of whom live within a mile of the Toomes-Petty House on Branson Milll Road. Thanks to Richard Petty and his daughter Rebecca Petty Moffitt for allowing me to research stuff like this while I supervised the move of the Petty Museum back to its old home.

[i] Full disclosure: I contributed photos and information to Wally’s book, but don’t let that keep you from buying it!

[ii] The Heritage of Randolph County, North Carolina (Vol. 1), p.108.

[iii] Ibid, p.109.

[iv] Guilford County, NC Apprentice Records, NC State Archives.

[v] All of the quoted Frank Toomes service records, both Confederate and Union, were accessed through http://www.fold3.com/, a website that specializes in historical U.S. military records.

[vi] Dalton is in the far northwest corner of Georgia, 27 miles east of Chickamauga and 32 miles south of Chattanooga. It lies at the south end of Mill Creek Gap, a strategic railroad passage through the mountains from Tennessee into the interior of Georgia. After the Confederate rout at Missionary Ridge in November 1863, Braxton Bragg made his headquarters at Dalton, where he was replaced by General Joe Johnston in December. There was no further action around Dalton until Sherman began his march into Georgia in May, 1864.

[vii] http://www.tngenweb.org/civilwar/rosters/cav/cav10/memo.html

[viii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/10th_Regiment_Tennessee_Volunteer_Cavalry

Tags: blacksmithing, Confederacy, cotton mills, deserters, quartermaster, Richard Petty, Toomes family

December 15, 2014 at 12:05 am |

The Frank Toomes farm was about a mile further east on Branson Mill Road from the modern site of Petty Enterprises. It was across the road from Branson’s Mill, which was previously known as Reynold’s Mill and, in the 18th century, as Macy’s Mill.

December 15, 2014 at 12:23 am |

My detailed family tree of the Petty and Toomes family can be found on ancestry.com at http://trees.ancestry.com/tree/66834413/family?fpid=36162448297 .

It is public, but you may need to be a member to see it all.